[/caption]

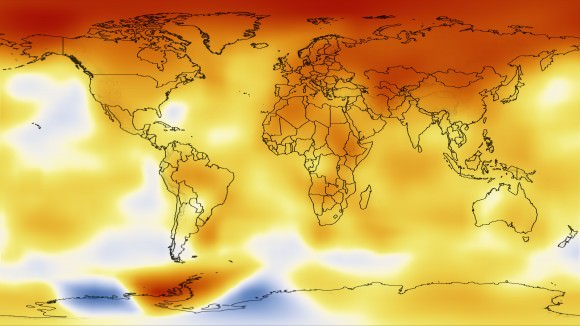

A new NASA report says the past decade was the warmest ever on Earth, at least since modern temperature measurements began in 1880. The study analyzed global surface temperatures and also found that 2009 was the second-warmest year on record, again since modern temperature measurements began. Last year was only a small fraction of a degree cooler than 2005, the warmest yet, putting 2009 in a virtual tie with the other hottest years, which have all occurred since 1998. This annual surface temperature study is one that always generates considerable interest — and some controversy. Gavin Schmidt, a climatologist at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS) offered some context on this latest report, in an interview with the NASA Earth Science News Team.

NASA’s Earth Science News Team: Every year, some of the same questions come up about the temperature record. What are they?

Gavin Schmidt: First, do the annual rankings mean anything? Second, how should we interpret all of the changes from year to year — or inter-annual variability — the ups and downs that occur in the record over short time periods? Third, why does NASA GISS get a slightly different answer than the Met Office Hadley Centre does? Fourth, is GISS somehow cooking the books in its handling and analysis of the data?

NASA: 2009 just came in as tied as the 2nd warmest on record, which seems notable. What is the significance of the yearly temperature rankings?

Gavin Schmidt: In fact, for any individual year, the ranking isn’t particularly meaningful. The difference between the second warmest and sixth warmest years, for example, is trivial. The media is always interested in the annual rankings, but whether it’s 2003, 2007, or 2009 that’s second warmest doesn’t really mean much because the difference between the years is so small. The rankings are more meaningful as you look at longer averages and decade-long trends.

NASA: Why does GISS get a different answer than the Met Office Hadley Centre [a UK climate research group that works jointly with the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia to perform an analysis of global temperatures]?

Gavin Schmidt: It’s mainly related to the way the weather station data is extrapolated. The Hadley Centre uses basically the same data sets as GISS, for example, but it doesn’t fill in large areas of the Arctic and Antarctic regions where fixed monitoring stations don’t exist. Instead of leaving those areas out from our analysis, you can use numbers from the nearest available stations, as long as they are within 1,200 kilometers. Overall, this gives the GISS product more complete coverage of the polar areas.

NASA: Some might hear the word “extrapolate” and conclude that you’re “making up” data. How would you reply to such criticism?

Gavin Schmidt: The assumption is simply that the Arctic Ocean as a whole is warming at the average of the stations around it. What people forget is that if you don’t put any values in for the areas where stations are sparse, then when you go to calculate the global mean, you’re actually assuming that the Arctic is warming at the same rate as the global mean. So, either way you are making an assumption.

Which one of those is the better assumption? Given all the changes we’ve observed in the Arctic sea ice with satellites, we believe it’s better to assume the Arctic Ocean is changing at the same rate as the other stations around the Arctic. That’s given GISS a slightly larger warming, particularly in the last couple of years, relative to the Hadley Centre.

NASA: Many have noted that the winter has been particularly cold and snowy in some parts of the United States and elsewhere. Does this mean that climate change isn’t happening?

Gavin Schmidt: No, it doesn’t, though you can’t dismiss people’s concerns and questions about the fact that local temperatures have been cool. Just remember that there’s always going to be variability. That’s weather. As a result, some areas will still have occasionally cool temperatures — even record-breaking cool — as average temperatures are expected to continue to rise globally.

NASA: So what’s happening in the United States may be quite different than what’s happening in other areas of the world?

Gavin Schmidt: Yes, especially for short time periods. Keep in mind that that the contiguous United States represents just 1.5 percent of Earth’s surface.

NASA: GISS has been accused by critics of manipulating data. Has this changed the way that GISS handles its temperature data?

Gavin Schmidt: Indeed, there are people who believe that GISS uses its own private data or somehow massages the data to get the answer we want. That’s completely inaccurate. We do an analysis of the publicly available data that is collected by other groups. All of the data is available to the public for download, as are the computer programs used to analyze it. One of the reasons the GISS numbers are used and quoted so widely by scientists is that the process is completely open to outside scrutiny.

NASA: What about the meteorological stations? There have been suggestions that some of the stations are located in the wrong place, are using outdated instrumentation, etc.

Gavin Schmidt: Global weather services gather far more data than we need. To get the structure of the monthly or yearly anomalies over the United States, for example, you’d just need a handful of stations, but there are actually some 1,100 of them. You could throw out 50 percent of the station data or more, and you’d get basically the same answers. Individual stations do get old and break down, since they’re exposed to the elements, but this is just one of things that the NOAA has to deal with. One recent innovation is the set up of a climate reference network alongside the current stations so that they can look for potentially serious issues at the large scale – and they haven’t found any yet.

Sources: NASA, NASA Earth Observatory

So you might want to rethink that next coastal real estate purchase – or hope for the best from

So you might want to rethink that next coastal real estate purchase – or hope for the best from