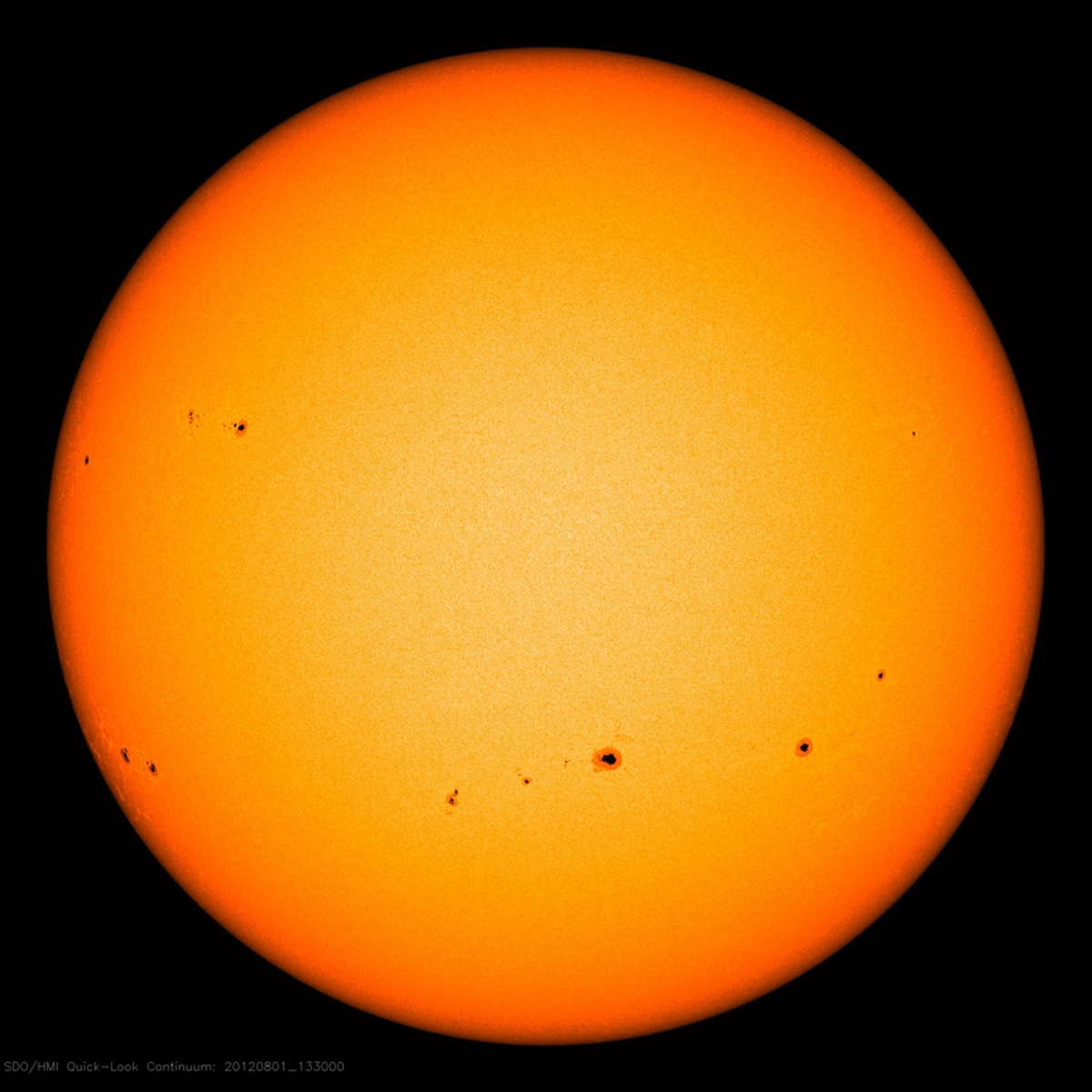

Here’s some beauty for your timeline: a stunning and ancient globular cluster captured by the venerable Hubble Space Telescope. The telescope’s Wide Field Camera 3 and Advanced Camera for Surveys was used to take this picture of ESO 520-21 (also known as Palomar 6), which is located about 25,000 light years away from Earth. Scientists say this globular cluster is probably about 12.4 billion years old.

Continue reading “No News Here, Just a Beautiful Globular Cluster Captured by Hubble. That is all.”A Cluster of Black Holes Found Inside a Globular Cluster of Stars

Black holes come in at least two sizes: small and large. Small black holes are formed from stars. When a large star reaches the end of its life, it typically ends in a supernova. The remnant core then collapses under its own weight, forming a black hole or neutron star. Small stellar-mass black holes are typically tens of solar masses. Large black holes lurk in the centers of galaxies. These supermassive black holes can be millions or billions of solar masses. They formed during the early universe and triggered the formation and evolution of galaxies around them.

Continue reading “A Cluster of Black Holes Found Inside a Globular Cluster of Stars”7% of the Stars in the Milky Way’s Center Came From a Single Globular Cluster That Got Too Close and Was Broken Up

The heart of the Milky Way can be a mysterious place. A gigantic black hole resides there, and it’s surrounded by a retinue of stars that astronomers call a Nuclear Star Cluster (NSC). The NSC is one of the densest populations of stars in the Universe. There are about 20 million stars in the innermost 26 light years of the galaxy.

New research shows that about 7% of the stars in the NSC came from a single source: a globular cluster of stars that fell into the Milky Way between 3 and 5 billion years ago.

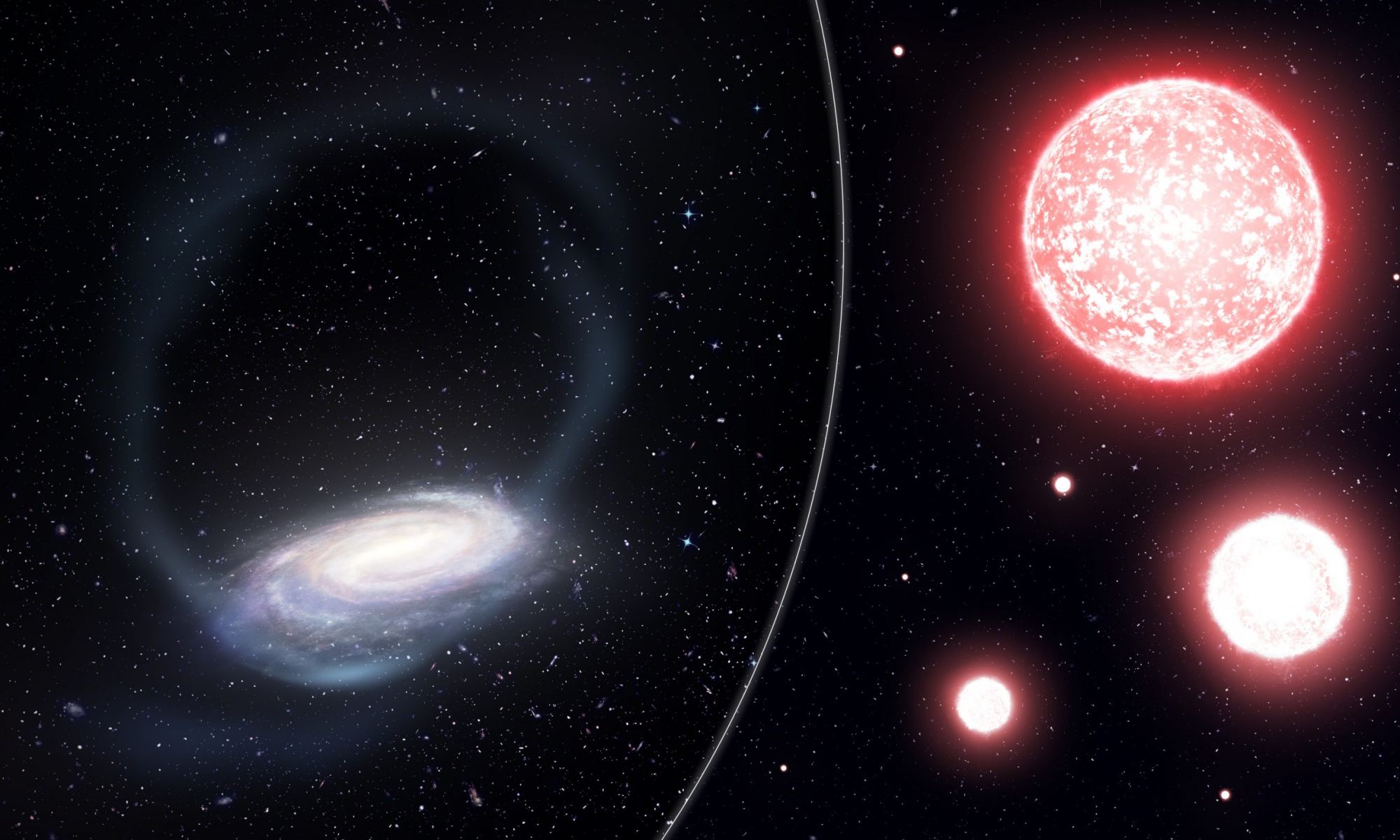

Continue reading “7% of the Stars in the Milky Way’s Center Came From a Single Globular Cluster That Got Too Close and Was Broken Up”A Globular Cluster was Completely Dismantled and Turned Into a Ring Around the Milky Way

According to predominant theories of galaxy formation, the earliest galaxies in the Universe were born from the merger of globular clusters, which were in turn created by the first stars coming together. Today, these spherical clusters of stars are found orbiting around the a galactic core of every observable galaxy and are a boon for astronomers seeking to study galaxy formation and some of the oldest stars in the Universe.

Interestingly enough, it appears that some of these globular clusters may not have survived the merger process. According to a new study by an international team of astronomers, a cluster was torn apart by our very own galaxy about two billion years ago. This is evidenced by the presence of a metal-poor debris ring that they observed wrapped around the entire Milky Way, a remnant from this ancient collision.

Continue reading “A Globular Cluster was Completely Dismantled and Turned Into a Ring Around the Milky Way”Hubble Captured a Photo of This Huge Spiral Galaxy, 2.5 Times Bigger than the Milky Way With 10 Times the Stars

This galaxy looks a lot like our own Milky Way galaxy. But while our galaxy is actively forming lots of new stars, this one is birthing stars at only half the rate of the Milky Way. It’s been mostly quiet for billions of years, feeding lightly on the thin gas in intergalactic space.

Continue reading “Hubble Captured a Photo of This Huge Spiral Galaxy, 2.5 Times Bigger than the Milky Way With 10 Times the Stars”Astronomers Find One of the Sun’s Sibling Stars. Born From the Same Solar Nebula Billions of Years Ago

According to current cosmological theories, the Milky Way started to form approximately 13.5 billion years ago, just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. This began with globular clusters, which were made up of some of the oldest stars in the Universe, coming together to form a larger galaxy. Over time, the Milky Way cannibalized several smaller galaxies within its cosmic neighborhood, growing into the spiral galaxy we know today.

Many new stars formed as mergers added more clouds of dust and gas and caused them to undergo gravitational collapse. In fact, it is believed that our Sun was part of a cluster that formed 4.6 billion years ago and that its siblings have since been distributed across the galaxy. Luckily, an international team of astronomers recently used a novel method to locate one of the Sun’s long-lost “solar siblings“, which just happens to be an identical twin!

Astronomy Cast Ep. 497: Update on Globular Clusters

Is it globular clusters or is it globeular clusters? It doesn’t matter, they’re awesome and we’re here to update you on them.

We usually record Astronomy Cast every Friday at 3:00 pm EST / 12:00 pm PST / 20:00 PM UTC. You can watch us live on AstronomyCast.com, or the AstronomyCast YouTube page.

Visit the Astronomy Cast Page to subscribe to the audio podcast!

If you would like to support Astronomy Cast, please visit our page at Patreon here – https://www.patreon.com/astronomycast. We greatly appreciate your support!

If you would like to join the Weekly Space Hangout Crew, visit their site here and sign up. They’re a great team who can help you join our online discussions!

Globular Clusters Might not be as Old as Astronomers Thought. Like, Billions of Years Younger

Globular clusters have been a source of fascination ever since astronomers first observed them in the 17th century. These spherical collections of stars are among the oldest known stars in the Universe, and can be found in the outer regions of most galaxies. Because of their age and the fact that almost all larger galaxies appear to have them, their role in galactic evolution has remained something of a mystery.

Previously, astronomers were of the opinion that globular clusters were some of the earliest stars to have formed in the Universe, roughly 13 billion years ago. However, new research has indicated that these clusters may actually be about 4 billion years younger, being roughly 9 billion years old. These findings may alter our understanding of how the Milky Way and other galaxies formed, and how the Universe itself came to be.

The study, titled “Reevaluating Old Stellar Populations“, recently appeared online and is being evaluated for publication in The Monthly Notices for the Royal Astronomical Society. The study was led by Dr. Elizabeth Stanway, an Associate Professor in the Astronomy group at the University of Warwick, UK, and was assisted by Dr. J.J. Eldridge, a Senior Lecturer at the University of Auckland, New Zealand.

For the sake of their study, Dr. Stanway and Dr. Eldridge developed a series of new research models designed to reconsider the evolution of stars. These models, known as Binary Population and Spectral Synthesis (BPASS) models, had previously proven effective in exploring the properties of young stellar populations within the Milky Way and throughout the Universe.

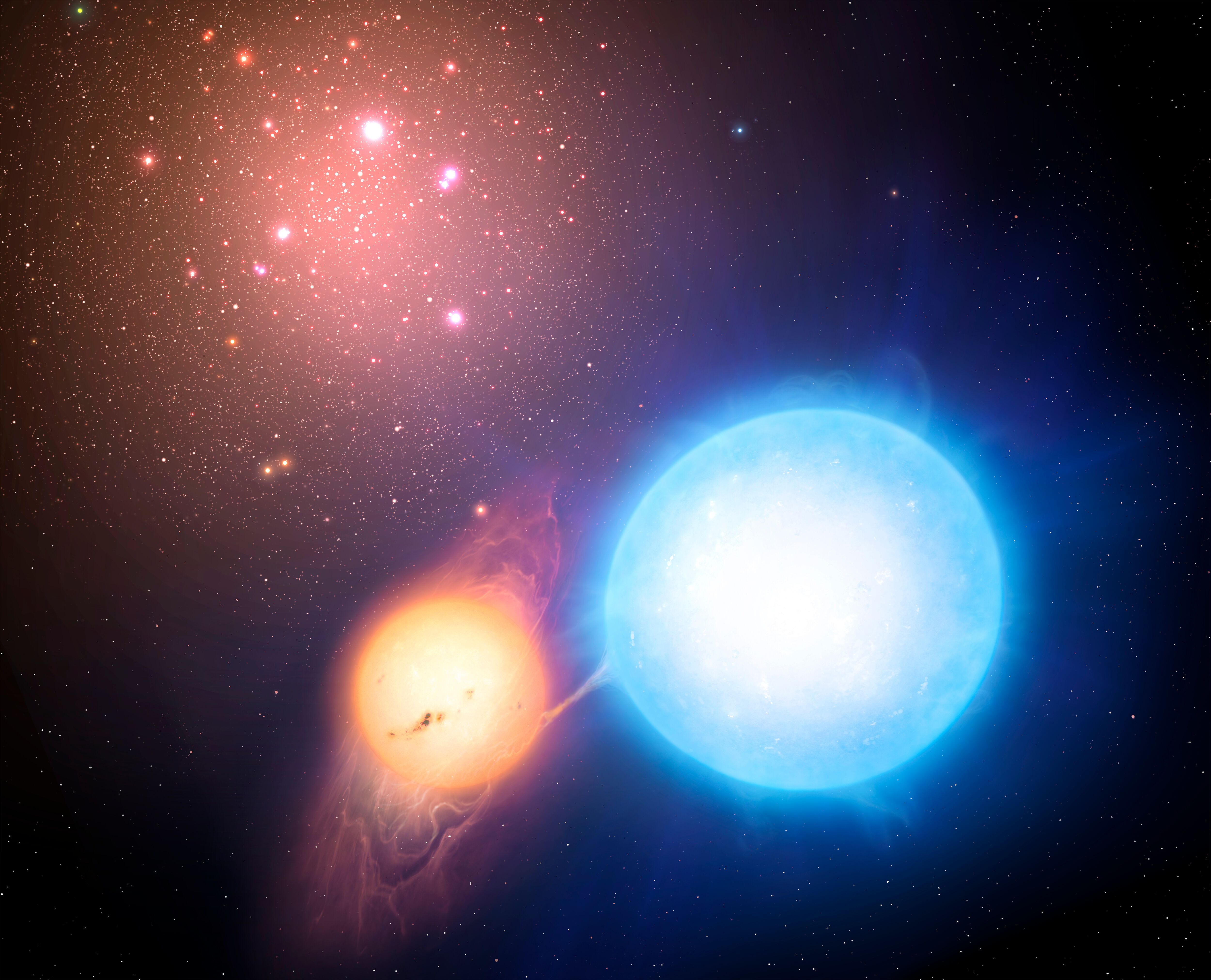

Using these same models, Dr. Stanway and Dr. Eldridge studied a sample of globular clusters in the Milky Way and nearby quiescent galaxies. They also took into account the details of binary star evolution within globular clusters and used them to explore the colors of light and spectra from old binary populations. In short, binary star system evolution consists of one star expanding into a giant while the gravitational force of the smaller star strips away the atmosphere of the giant.

What they found was that these binary systems were about 9 billion years old. Since these stars are thought to have formed at the same time as the globular clusters themselves, this demonstrated that globular clusters are not as old as other models have suggested. As Dr. Stanway said of the BPASS models she and Dr. Eldridge developed:

“Determining ages for stars has always depended on comparing observations to the models which encapsulate our understanding of how stars form and evolve. That understanding has changed over time, and we have been increasingly aware of the effects of stellar multiplicity – the interactions between stars and their binary and tertiary companions.

If correct, this study could open up new pathways of research into how massive galaxies and their stars are formed. However, Dr. Stanway admits that much work still lies ahead, which includes looking at nearby star systems where individual stars can be resolved – rather than considering the integrated light of a cluster. Nevertheless, the study could have immense significant for our understanding of how and when galaxies in our Universe formed.

“If true, it changes our picture of the early stages of galaxy evolution and where the stars that have ended up in today’s massive galaxies, such as the Milky Way, may have formed,” she said. “We aim to follow up this research in the future, exploring both improvements in modelling and the observable predictions which arise from them.”

An integral part of cosmology is understanding when the Universe came to be the way it is, not just how. By determining how old globular clusters are, astronomers will have another crucial piece of the puzzle as to how and when the earliest galaxies formed. And these, combined with observations that look to the earliest epochs of the Universe, could just yield a complete model of cosmology.

Further Reading: University of Warwick, arXiv

A Black Hole is Pushing the Stars Around in this Globular Cluster

Astronomers have been fascinated with globular clusters ever since they were first observed in 17th century. These spherical collections of stars are among the oldest known stellar systems in the Universe, dating back to the early Universe when galaxies were just beginning to grow and evolve. Such clusters orbit the centers of most galaxies, with over 150 known to belong to the Milky Way alone.

One of these clusters is known as NGC 3201, a cluster located about 16,300 light years away in the southern constellation of Vela. Using the ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) at the Paranal Observatory in Chile, a team of astronomers recently studied this cluster and noticed something very interesting. According to the study they released, this cluster appears to have a black hole embedded in it.

The study appeared in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society under the title “A detached stellar-mass black hole candidate in the globular cluster NGC 3201“. The study was led by Benjamin Giesers of the Georg-August-University of Göttingen and included members from Liverpool John Moores University, Queen Mary University of London, the Leiden Observatory, the Institute of Astrophysics and Space Sciences, ETH Zurich, and the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP).

For the sake of their study, the team relied on the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) instrument on the VLT to observe NGC 3201. This instrument is unique because of the way it allows astronomers to measure the motions of thousands of far away stars simultaneously. In the course of their observations, the team found that one of the cluster’s stars was being flung around at speeds of several hundred kilometers an hour and with a period of 167 days.

As Giesers explained in an ESO press release:

“It was orbiting something that was completely invisible, which had a mass more than four times the Sun — this could only be a black hole! The first one found in a globular cluster by directly observing its gravitational pull.”

This finding was rather unexpected, and constitutes the first time that astronomers have been able to detect an inactive black hole at the heart of a globular cluster – meaning that it is not currently accreting matter or surrounded by a glowing disc of gas. They were also able to estimate the black hole’s mass by measuring the movements of the star around it and thus extrapolating its enormous gravitational pull.

From its observed properties, the team determined that the rapidly-moving star is about 0.8 times the mass of our Sun and the mass of its black hole counterpart to be around 4.36 times the Sun’s mass. This put’s it in the “stellar-mass black hole” category, which are stars that exceeds the maximum mass allowance of a neutron star, but are smaller than supermassive black holes (SMBHs) – which exist at the centers of most galaxies.

This finding is highly significant, and not just because it was the first time that astronomers have observed a stellar-mass black hole in a globular cluster. In addition, it confirms what scientists have been suspecting for a few years now, thanks to recent radio and x-ray studies of globular clusters and the detection of gravity wave signals. Basically, it indicates that black holes are more common in globular clusters than previously thought.

“Until recently, it was assumed that almost all black holes would disappear from globular clusters after a short time and that systems like this should not even exist!” said Giesers. “But clearly this is not the case – our discovery is the first direct detection of the gravitational effects of a stellar-mass black hole in a globular cluster. This finding helps in understanding the formation of globular clusters and the evolution of black holes and binary systems – vital in the context of understanding gravitational wave sources.”

This find was also significant given that the relationship between black holes and globular clusters remains a mysterious, but highly important one. Due to their high masses, compact volumes, and great ages, astronomers believe that clusters have produced a large number of stellar-mass black holes over the course of the Universe’s history. This discovery could therefore tell us much about the formation of globular clusters, black holes, and the origins of gravitational wave events.

And be sure to enjoy this ESO podcast explaining the recent discovery:

Messier 12 (M12) – The NGC 6118 Globular Cluster

Welcome back to another edition of Messier Monday! Today, we continue in our tribute to Tammy Plotner with a look at the M12 globular cluster!

In the 18th century, French astronomer Charles Messier noted the presence of several “nebulous objects” in the night sky which he originally mistook for comets. After realizing his mistake, he began compiling a list of these objects in order to ensure that other astronomers did not make the same error. In time, this list would include 100 objects, and would come to be known as the Messier Catalog to posterity.

One the many objects included in this is Messier 12 (aka. M12 or NGC 6218), a globular cluster located in the Ophiuchus constellation some 15,700 light-years from Earth. M12 is positioned just 3° from the cluster M10, and the two are among the brightest of the seven Messier globulars located in Ophiuchus. It is also interesting to note that M12 is approaching our Solar System at a velocity of 16 km/s.

Continue reading “Messier 12 (M12) – The NGC 6118 Globular Cluster”