[/caption]

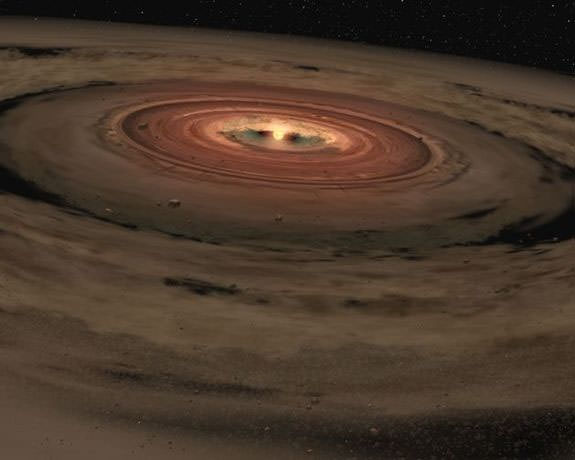

Jupiter hasn’t always been in the same place in our solar system. Early in the history of our solar system, Jupiter moved inward towards the sun, almost to where Mars currently orbits now, and then back out to its current position.

The migration through our solar system of Jupiter had some major effects on our solar system. Some of the effects of Jupiter’s wanderings include effects on the asteroid belt and the stunted growth of Mars.

What other effects did Jupiter’s migration have on the early solar system and how did scientists make this discovery?

In a research paper published in the July 14th issue of Nature, First author Kevin Walsh and his team created a model of the early solar system which helps explain Jupiter’s migration. The team’s model shows that Jupiter formed at a distance of around 3.5 A.U (Jupiter is currently just over 5 A.U from the sun) and was pulled inward by currents in the gas clouds that still surrounded the sun at the time. Over time, Jupiter moved inward slowly, nearly reaching the same distance from the sun as the current orbit of Mars, which hadn’t formed yet.

“We theorize that Jupiter stopped migrating toward the sun because of Saturn,” said Avi Mandell, one of the paper’s co-authors. The team’s data showed that Jupiter and Saturn both migrated inward and then outward. In the case of Jupiter, the gas giant settled into its current orbit at just over 5 a.u. Saturn ended its initial outward movement at around 7 A.U, but later moved even further to its current position around 9.5 A.U.

Astronomers have had long-standing questions regarding the mixed composition of the asteroid belt, which includes rocky and icy bodies. One other puzzle of our solar system’s evolution is what caused Mars to not develop to a size comparable to Earth or Venus.

Regarding the asteroid belt, Mandell explained, “Jupiter’s migration process was slow, so when it neared the asteroid belt, it was not a violent collision but more of a do-si-do, with Jupiter deflecting the objects and essentially switching places with the asteroid belt.”

Jupiter’s slow movement caused more of a gentle “nudging” of the asteroid belt when it passed through on its inward movement. When Jupiter moved back outward, the planet moved past the location it originally formed. One side-effect of caused by Jupiter moving further out from its original formation area is that it entered the region of our early solar system where icy objects were. Jupiter pushed many of the icy objects inward towards the sun, causing them to end up in the asteroid belt.

“With the Grand Tack model, we actually set out to explain the formation of a small Mars, and in doing so, we had to account for the asteroid belt,” said Walsh. “To our surprise, the model’s explanation of the asteroid belt became one of the nicest results and helps us understand that region better than we did before.”

With regards to Mars, in theory Mars should have had a larger supply gas and dust, having formed further from the sun than Earth. If the model Walsh and his team developed is correct, Jupiter foray into the inner solar system would have scattered the material around 1.5 A.U.

Mandell added, “Why Mars is so small has been the unsolvable problem in the formation of our solar system. It was the team’s initial motivation for developing a new model of the formation of the solar system.”

An interesting scenario unfolds with Jupiter scattering material between 1 and 1.5 AU. Instead of the higher concentration of planet-building materials being further out, the high concentration led to Earth and Venus forming in a material-rich region.

The model Walsh and his team developed brings new insight into the relationship between the inner planets, our asteroid belt and Jupiter. The knowledge learned not only will allow scientists to better understand our solar system, but helps explain the formation of planets in other star systems. Walsh also mentioned, “Knowing that our own planets moved around a lot in the past makes our solar system much more like our neighbors than we previously thought. We’re not an outlier anymore.”

If you’d like to access the paper (subscription or paid/university access required), you can do so at: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v475/n7355/full/nature10201.html

Source: NASA Solar System News, Nature