[/caption]

And just where have your buckyballs been lately? More technically known as fullerenes, this magnetic form of carbon shows some pretty interesting properties deduced from laboratory work here on Earth. But even more interesting is its cousin – graphene. And guess where it’s been found?!

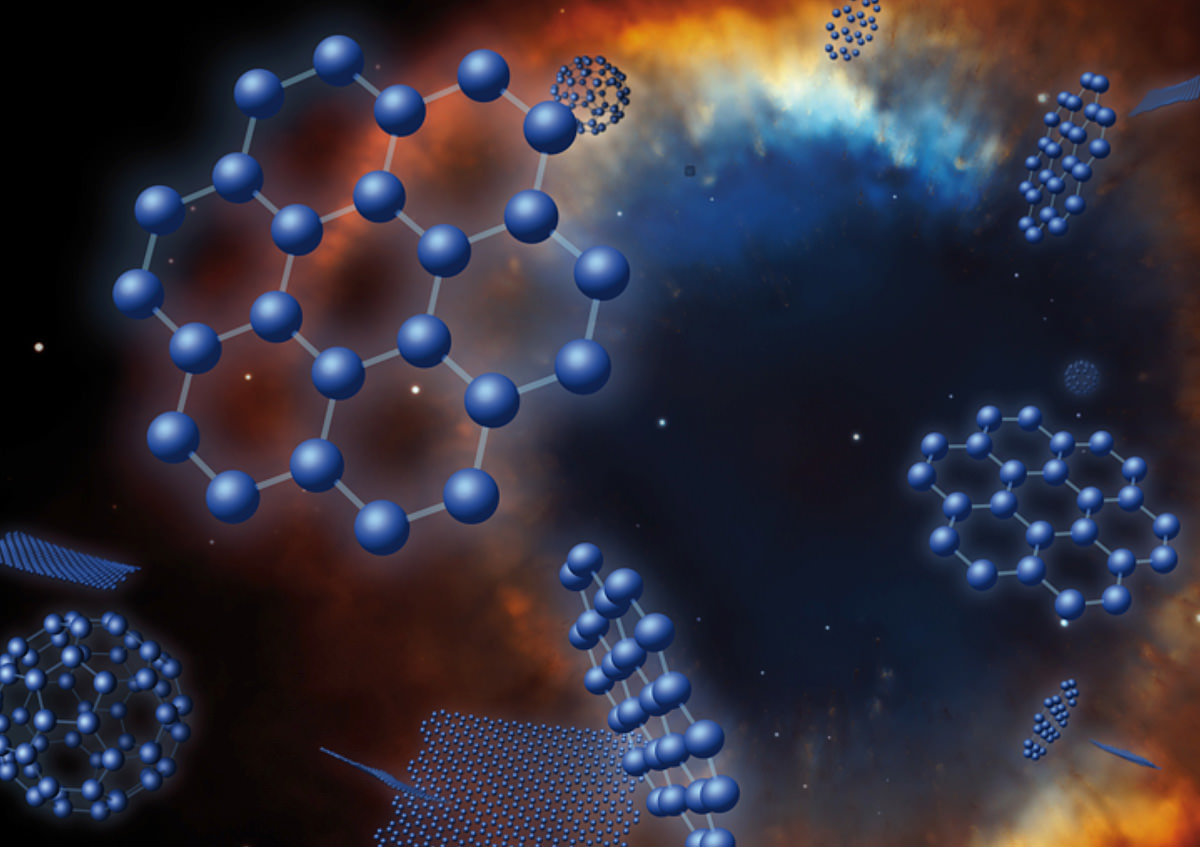

When you picture a fullerene, you conjure up a mental image of carbon atoms arranged in a three-dimensional configuration with two structures: C60 which patterns out similar to a soccer ball and C70 which more closely resembles a rugby ball. Both of these types of “buckyballs” have been detected in space, but the real kicker is graphene. Its technical name is planar C24 and instead of being geodesic, it’s the thinnest substance known. Just one atom thick, this flat sheet of carbon is a portrait in extraordinary strength, conductivity and elasticity. Graphene was first synthesized in the lab in 2004 and now planar C24 may have been detected in space.

Through the use of the Spitzer Space Telescope, a team of astronomers led by Domingo Aníbal García-Hernández of the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias in Spain have not only picked up a C70 fullerene molecule, but may have also detected graphene as well. “If confirmed with laboratory spectroscopy – something that is almost impossible with the present techniques – this would be the first detection of graphene in space” said García-Hernández.

Letizia Stanghellini and Richard Shaw, members of the team at the National Optical Astronomy Observatory in Tucson, Arizona suspect collisional shocks generated in stellar winds of planetary nebulae could be responsible for the presence of fullerenes and graphenes through the destruction of hydrogenated amorphous carbon grains (HACs). “What is particularly surprising is that the existence of these molecules does not depend on the stellar temperature, but on the strength of the wind shocks” says Stanghellini.

So where has this discovery taken place? Try the Magellanic Clouds. In this case, using a planetary nebula “closer to home” is not part of the equation because science needs to be certain the material they are looking at is indeed the by-product of a planetary nebula and not a mix. Fortunately the SMG is known to be metal-poor, which enhances the chances of spotting complex carbon molecules. Right now the challenge has been to pinpoint the evidence for graphene from Spitzer data.

“The Spitzer Space Telescope has been amazingly important for studying complex organic molecules in stellar environments” says Stanghellini. “We are now at the stage of not only detecting fullerenes and other molecules, but starting to understand how they form and evolve in stars.” Shaw adds “We are planning ground-based follow up through the NOAO system of telescopes. We hope to find other molecules in planetary nebulae where fullerene has been detected to test some physical processes that might help us understand the biochemistry of life.”

Original News Source: National Optical Astronomy Observatory News Release.