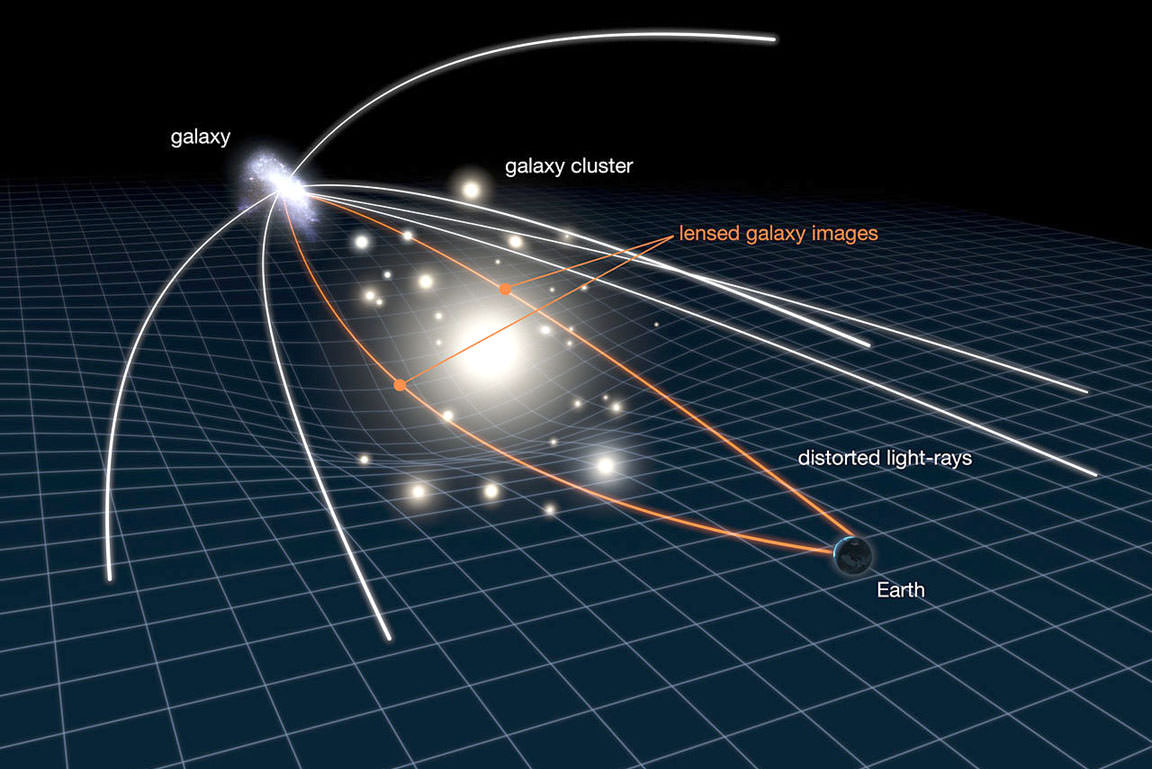

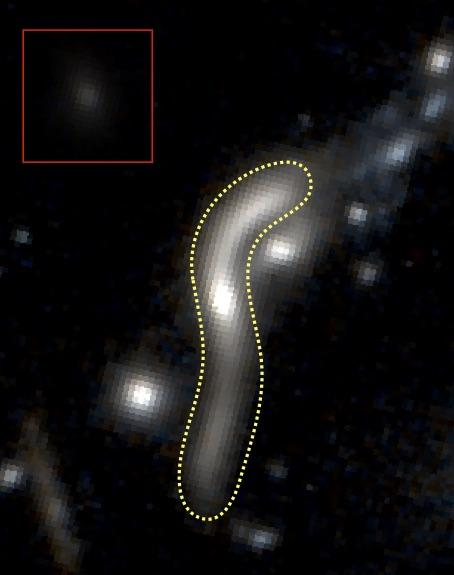

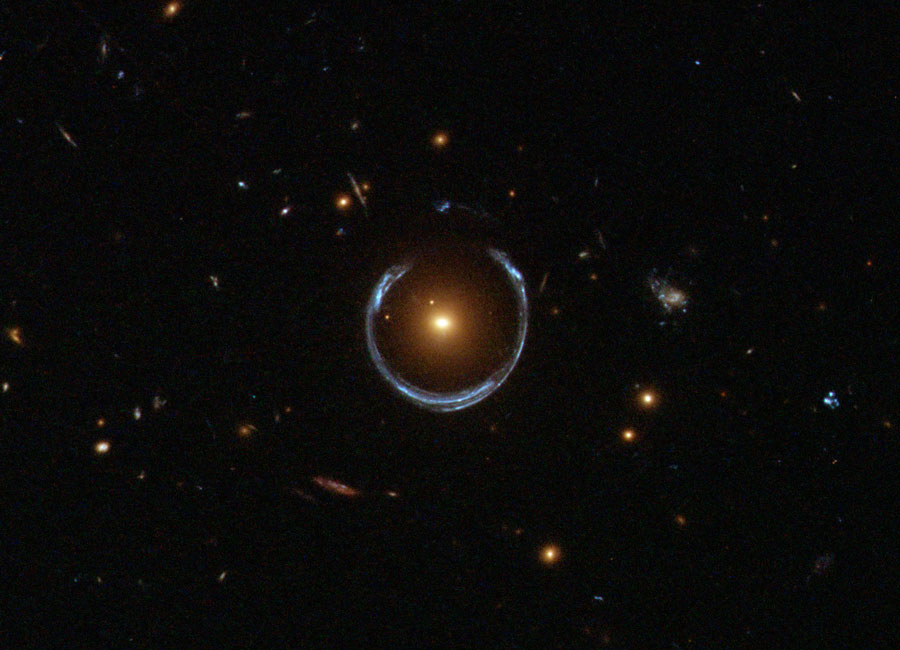

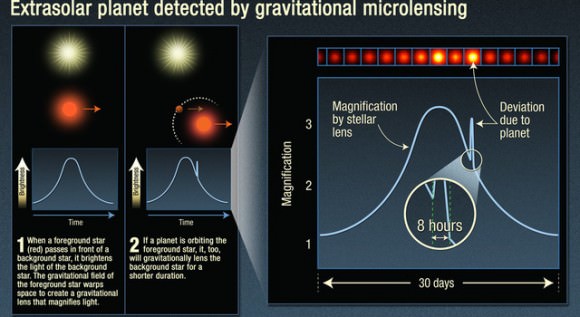

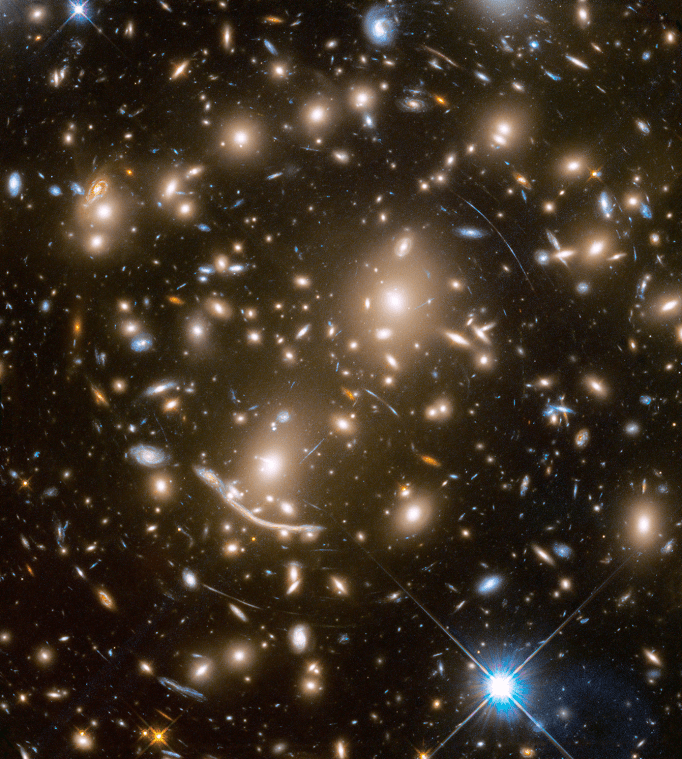

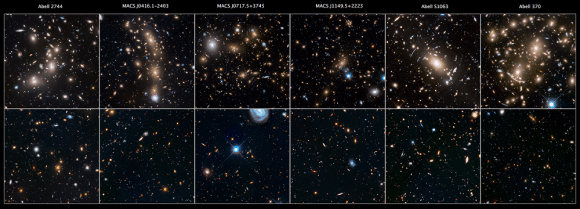

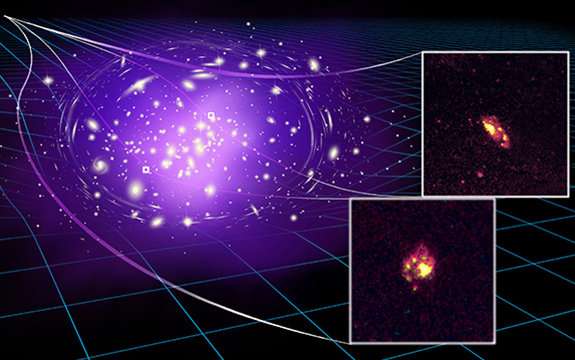

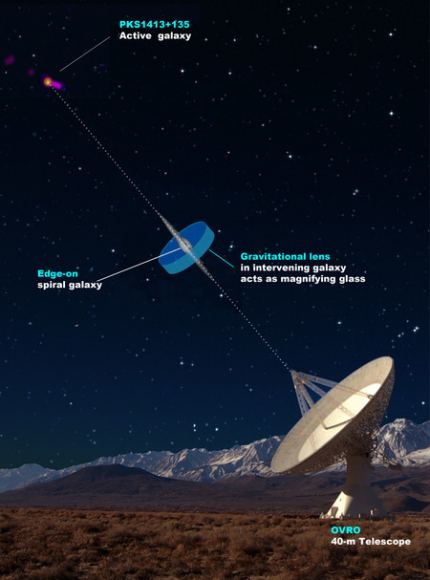

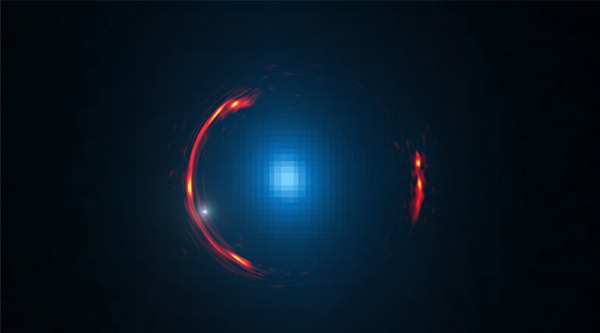

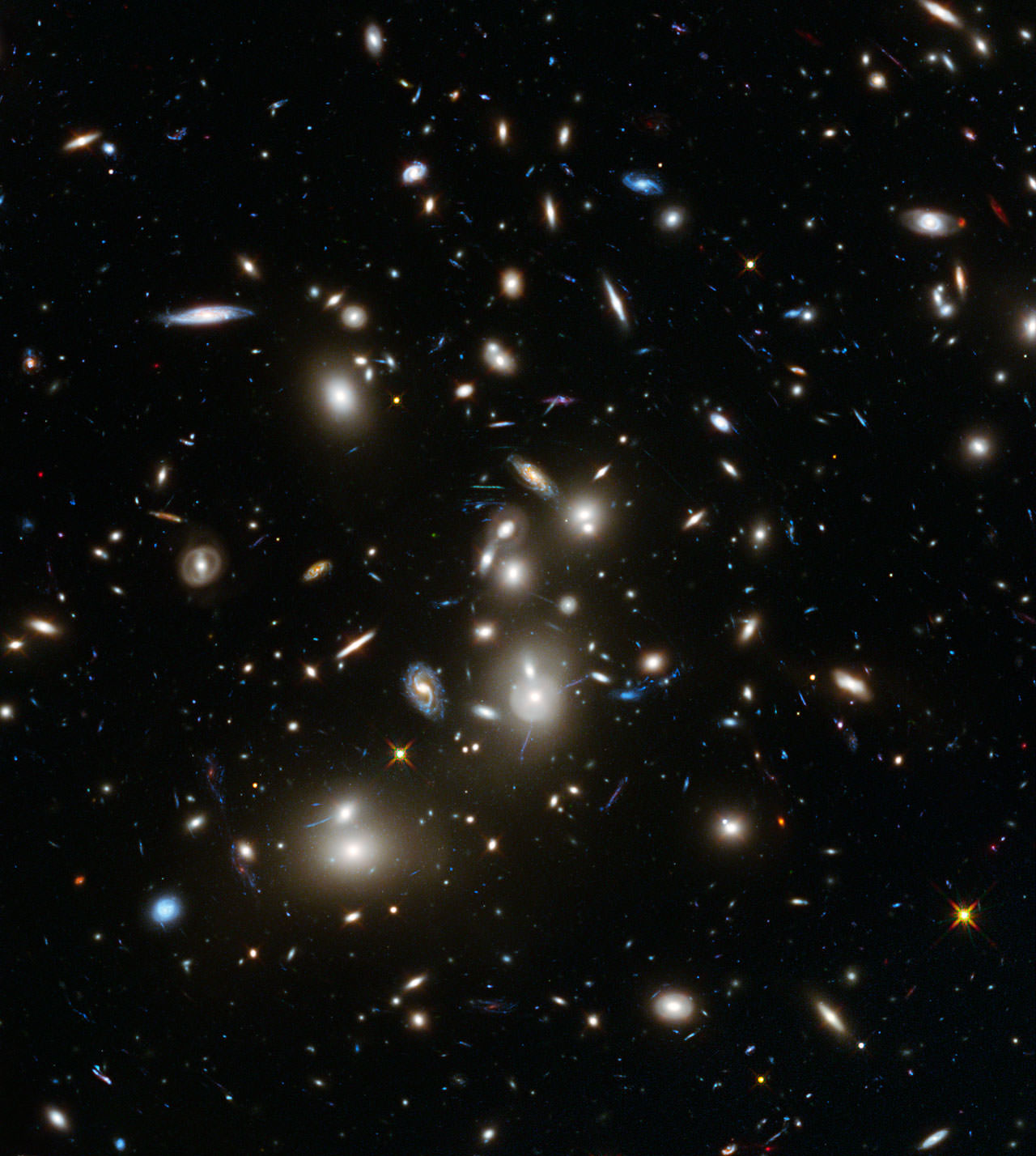

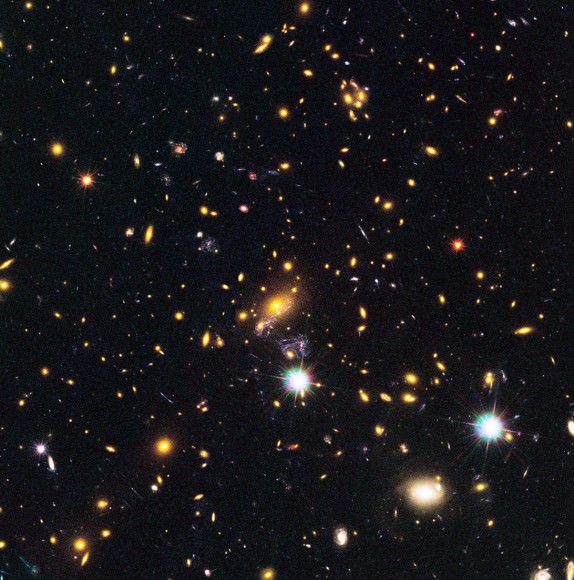

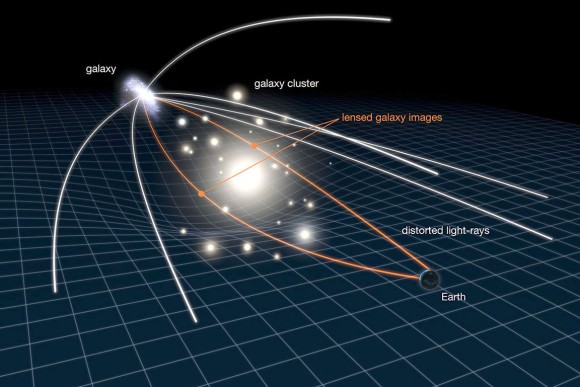

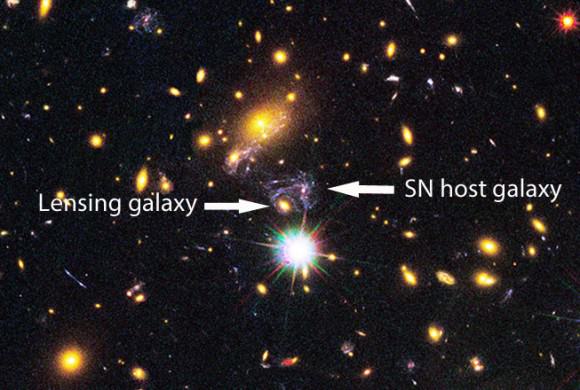

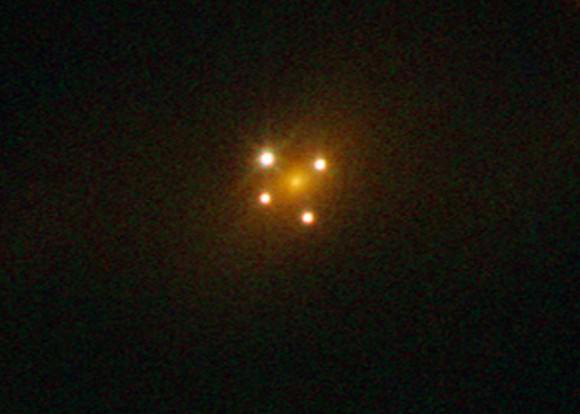

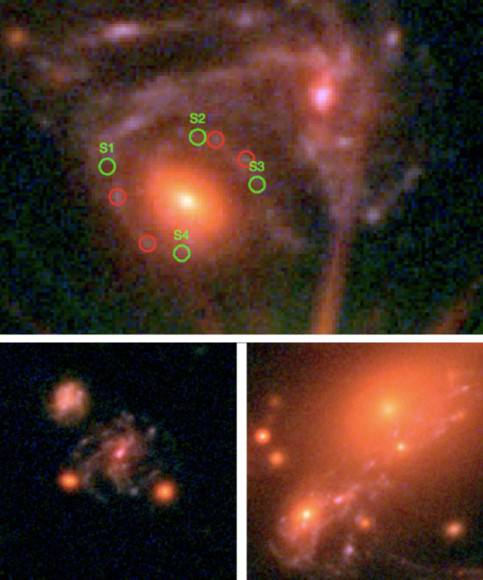

For the sake of studying the most distant objects in the Universe, astronomers often rely on a technique known as Gravitational Lensing. Based on the principles of Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, this technique involves relying on a large distribution of matter (such as a galaxy cluster or star) to magnify the light coming from a distant object, thereby making it appear brighter and larger.

However, in recent years, astronomers have found other uses for this technique as well. For instance, a team of scientists from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) recently determined that Gravitational Lensing could also be used to determine the mass of white dwarf stars. This discovery could lead to a new era in astronomy where the mass of fainter objects can be determined.

The study which details their findings, titled “Predicting gravitational lensing by stellar remnants” appeared in the Monthly Noticed of the Royal Astronomical Society. The study was led by Alexander J. Harding of the CfA and included Rosanne Di Stefano, and Claire Baker (also from the CfA), as well as members from the University of Southampton, Georgia State University, the University of Nigeria, and Cornell University.

To put it simply, determining the mass of an astronomical object is one the greatest challenges for astronomers. Until now, the most successful method relied on binary systems because the orbital parameters of these systems depend on the masses of the two objects. Unfortunately, objects that are at the end states of stellar evolution – like black holes, neutron stars or white dwarfs – are often too faint or isolated to be detectable.

This is unfortunate, since these objects are responsible for a lot of dramatic astronomical events. These include the accretion of material, the emission of energetic radiation, gravitational waves, gamma-ray bursts, or supernovae. Many of these events are still a mystery to astronomers or the study of them is still in its infancy – i.e. gravitational waves. As they state in their study:

“Gravitational lensing provides an alternative approach to mass measurement. It has the advantage of only relying on the light from a background source, and can therefore be employed even for dark lenses. In fact, since light from the lens can interfere with the detection of lensing effects, compact objects are ideal lenses.”

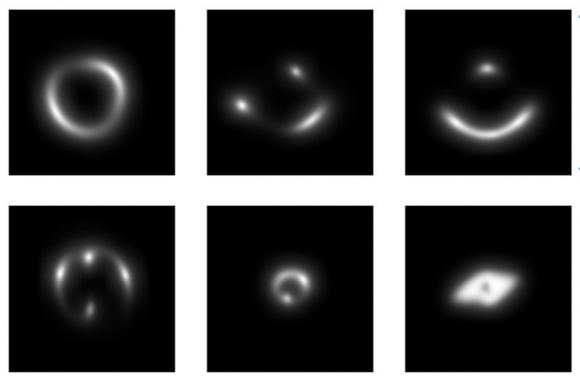

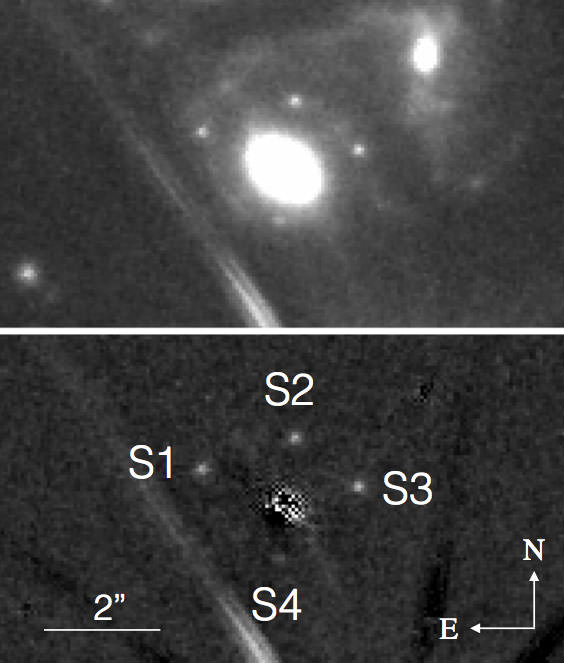

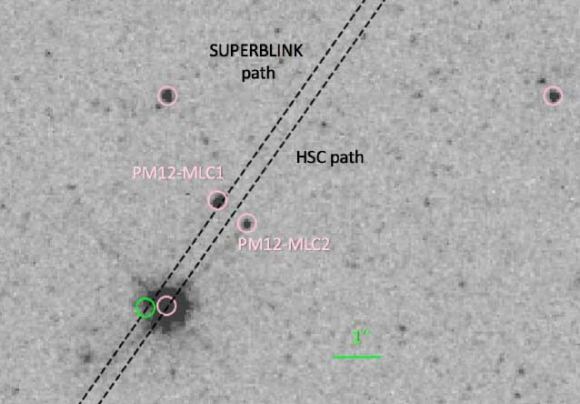

As they go on to state, of the 18,000 lensing events that have been detected to date, roughly 10 to 15% are believed to have been caused by compact objects. However, scientists are unable to tell which of the detected events were due to compact lenses. For the sake of their study then, the team sought to circumvent this problem by identifying local compact objects and predicting when they might produce a lensing event so they could be studied.

“By focusing on pre-selected compact objects in the near vicinity of the Sun, we ensure that the lensing event will be caused by a white dwarf, neutron star, or black hole,” they state. “Furthermore, the distance and proper motion of the lens can be accurately measured prior to the event, or else afterwards. Armed with this information, the lensing light curve allows one to accurately measure the mass of the lens.”

In the end, the team determined that lensing events could be predicted from thousands of local objects. These include 250 neutron stars, 5 black holes, and roughly 35,000 white dwarfs. Neutron stars and black holes present a challenge since the known populations are too small and their proper motions and/or distances are not generally known.

But in the case of white dwarfs, the authors anticipate that they will provide for many lensing opportunities in the future. Based on the general motions of the white dwarfs across the sky, they obtained a statistical estimate that about 30-50 lensing events will take place per decade that could be spotted by the Hubble Space Telescope, the ESA’s Gaia mission, or NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). As they state in their conclusions:

“We find that the detection of lensing events due to white dwarfs can certainly be observed during the next decade by both Gaia and HST. Photometric events will occur, but to detect them will require observations of the positions of hundreds to thousands of far-flung white dwarfs. As we learn the positions, distances to, and proper motions of larger numbers of white dwarfs through the completion of surveys such as Gaia and through ongoing and new wide-field surveys, the situation will continue to improve.”

The future of astronomy does indeed seem bright. Between improvements in technology, methodology, and the deployment of next-generation space and ground-based telescopes, there is no shortage of opportunities to see and learn more.