The quest for optimal sites to carry out astronomical observations has taken scientists to the frigid Arctic. Eric Steinbring, who led a team of National Research Council Canada experts, noted that a high Arctic site can, “offer excellent image quality that is maintained during many clear, calm, dark periods that can last 100 hours or more.” The new article by Steinbring and colleagues conveys recent progress made to obtain precise observations from a 600 m high ridge near the Eureka research base on Ellesmere Island, which is located in northern Canada.

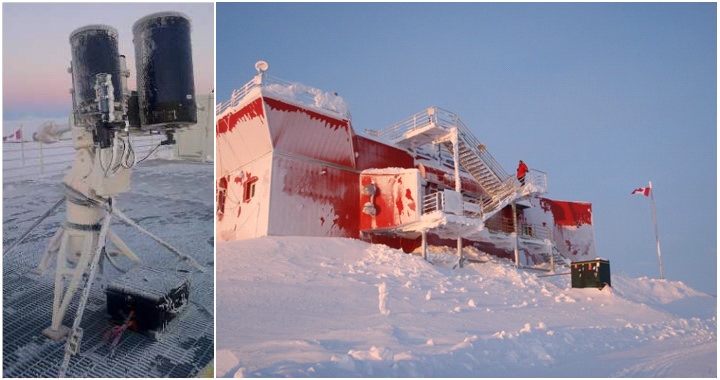

The new telescope that Steinbring and his colleagues tested was located at the Polar Environment Atmospheric Research Laboratory (PEARL). The observatory can be accessed in winter by 4 x 4 trucks via a 15 km long road from a base facility at sea-level. That base camp is operated by Environment Canada and serviced by an airstrip and resupply ship in summer. Recently, wide-field cameras developed at the University of Toronto were deployed near Eureka to monitor thousands of stars, with the objective of expanding the exoplanet database.

Earlier work by Steinbring and colleagues indicated that data obtained from PEARL imply that clear weather prevails 68% of the time. After significant testing, the team concluded that the site “can allow reliable, uninterrupted temporal coverage during successive dark periods, in roughly 100 hour blocks with clear skies and good seeing.”

However, the optimal conditions can be interrupted by brief but potentially intense storms. In the article the team added that, “the primary issue is wind rather than the cold temperatures.” The PEARL facility is equipped with an important weather probe that conveys on-site conditions at 10 minute intervals, thanks to the Canadian Network for the Detection of Atmospheric Change (CANDAC).

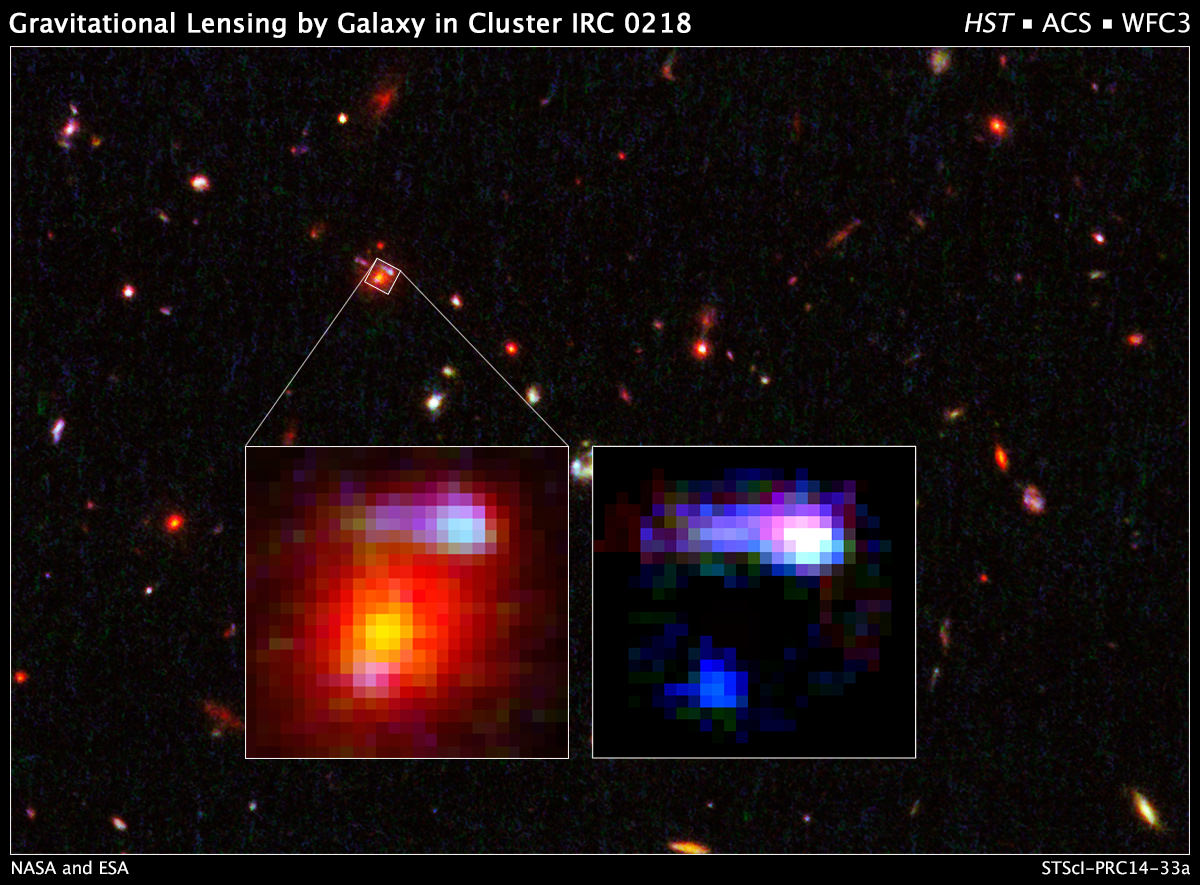

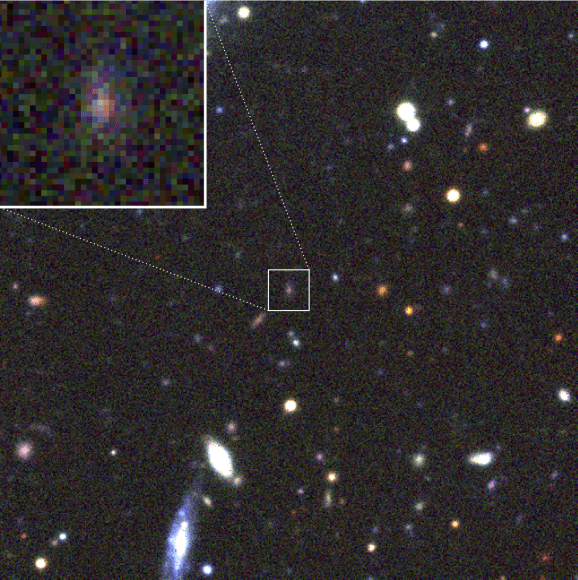

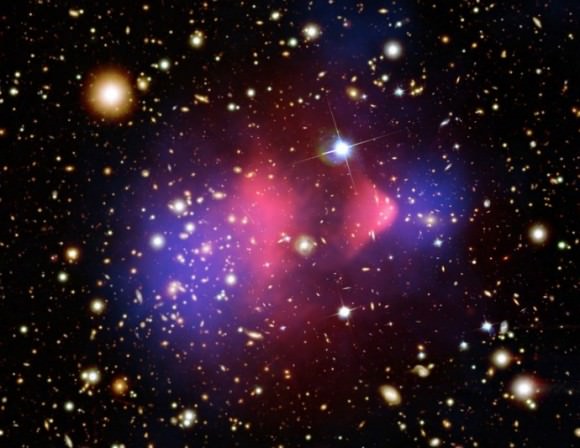

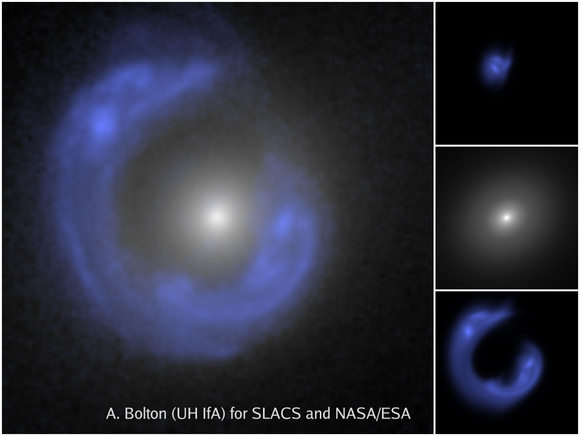

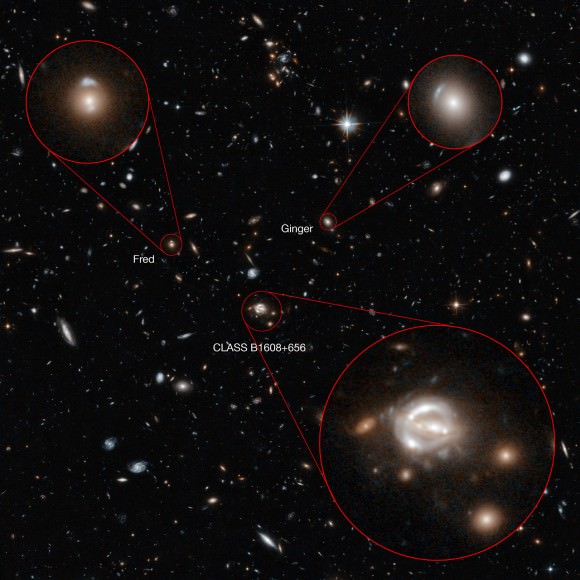

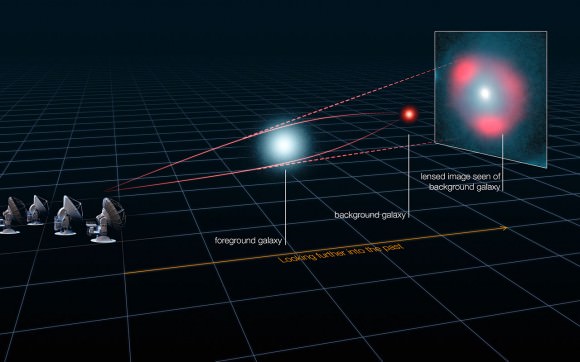

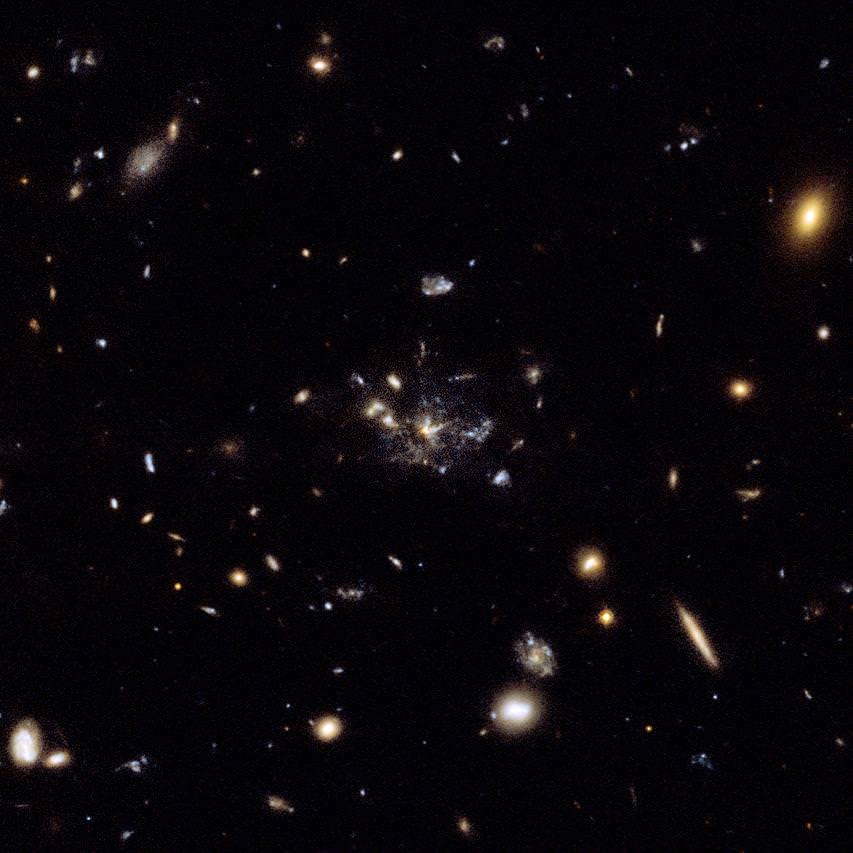

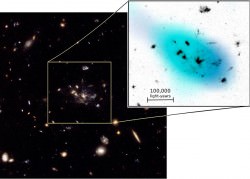

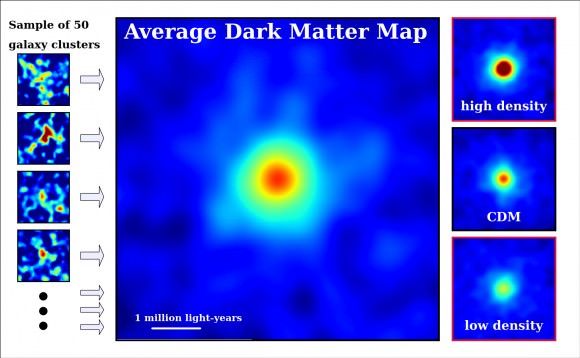

There are numerous challenges that arise when observing from the Arctic, but scientists like Steinbring have worked to overcome them, potentially enabling new studies of gravitational lenses and other pertinent phenomena. Indeed, astronomical observations are likewise being obtained from Antarctica. For example, there is the Antarctic Search for Transiting Exoplanets (ASTEP) 40 cm telescope at Dome C, and three 50 cm Antarctic Survey Telescopes (AST3) at Dome A, Antarctica. Steinbring remarked that floorspace is potentially available for up to 5 more telescopes at PEARL, if the compact design they studied was adopted.

E. Steinbring and his colleagues B. Leckie and R. Murowinski are associated with the National Research Council Canada, Herzberg Astronomy and Astrophysics in Victoria, Canada. An electronic preprint of their article is available on arXiv, and the findings were presented recently at the Adapting to the Atmosphere Conference in Durham, UK.