In February of 2016, scientists working for the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) made history when they announced the first-ever detection of gravitational waves. Since that time, multiple detections have taken place and scientific collaborations between observatories – like Advanced LIGO and Advanced Virgo – are allowing for unprecedented levels of sensitivity and data sharing.

Not only was the first-time detection of gravity waves an historic accomplishment, it ushered in a new era of astrophysics. It is little wonder then why the three researchers who were central to the first detection have been awarded the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics. The prize was awarded jointly to Caltech professors emeritus Kip S. Thorne and Barry C. Barish, along with MIT professor emeritus Rainer Weiss.

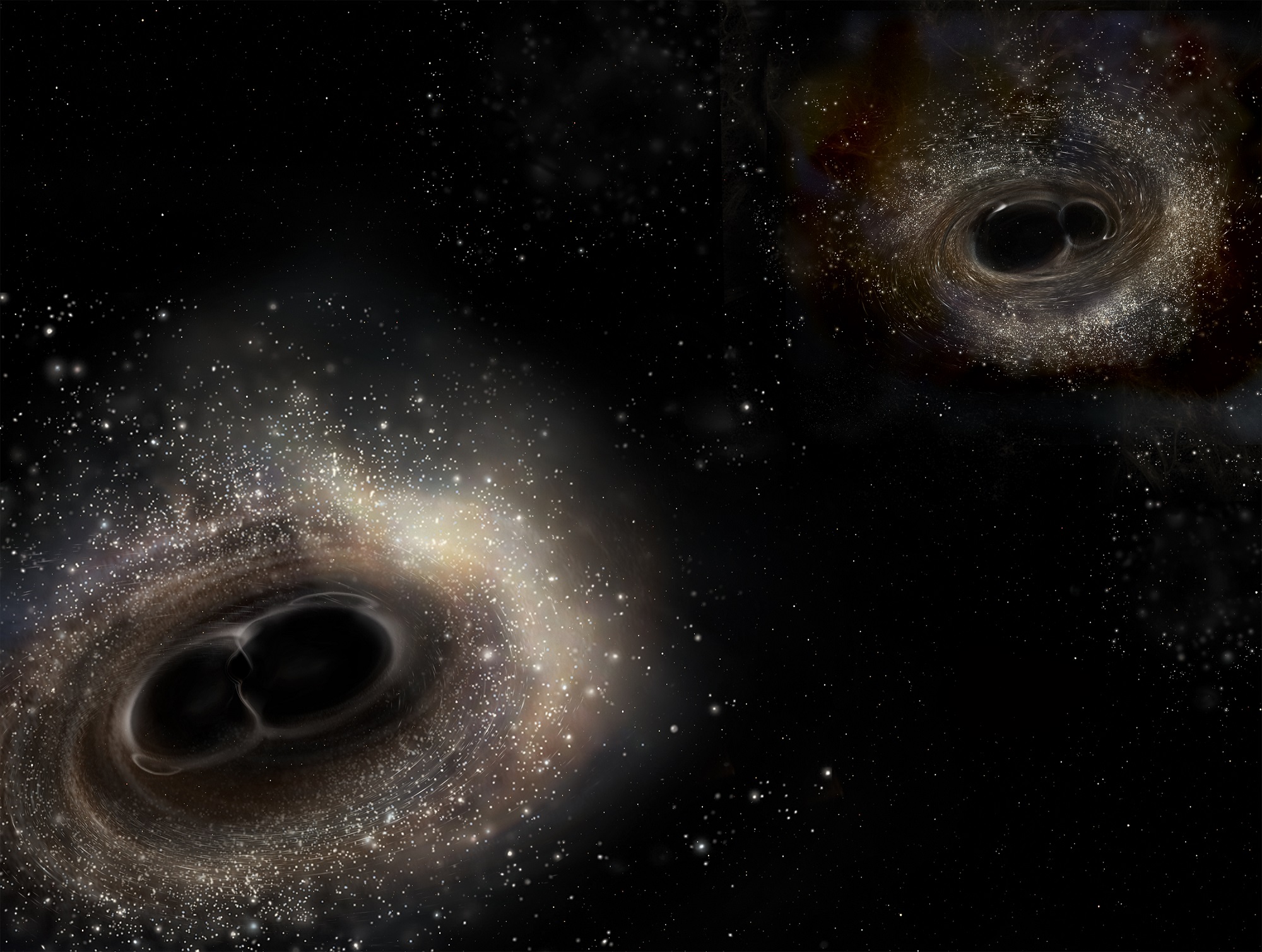

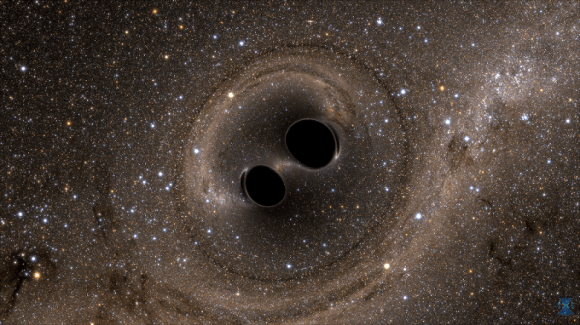

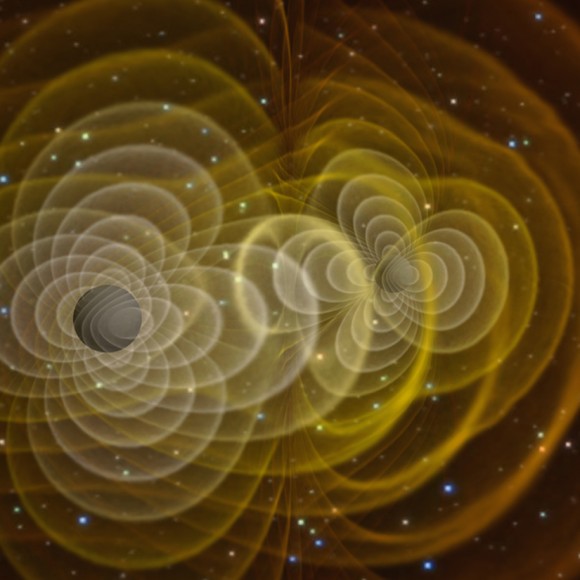

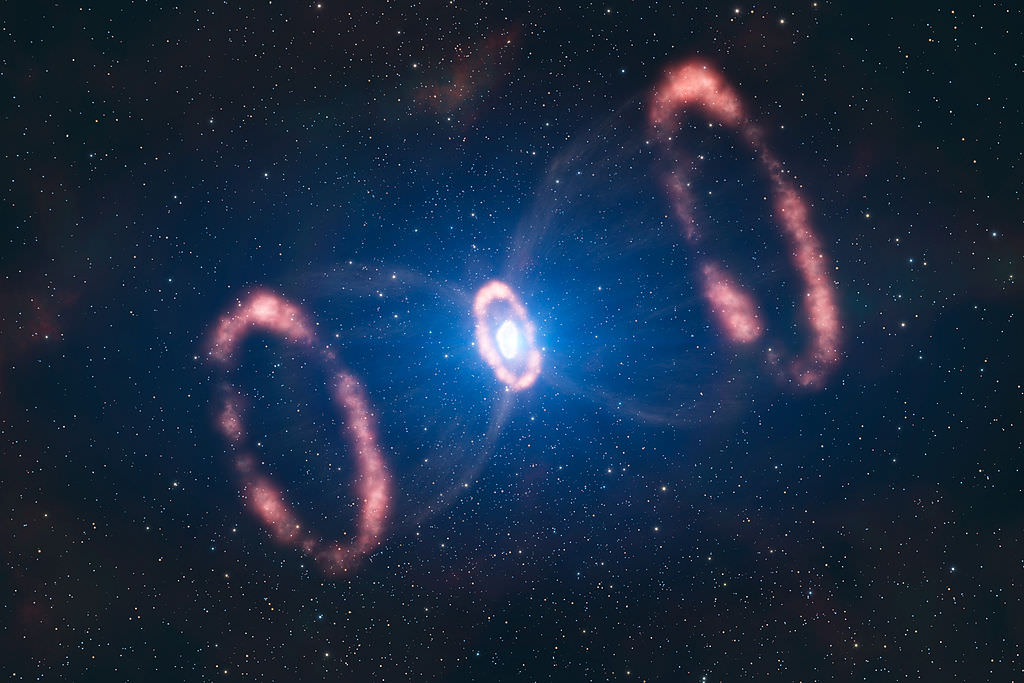

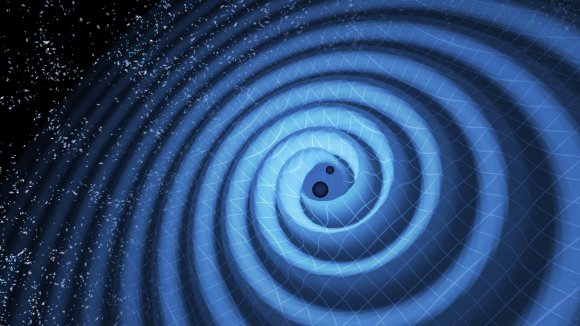

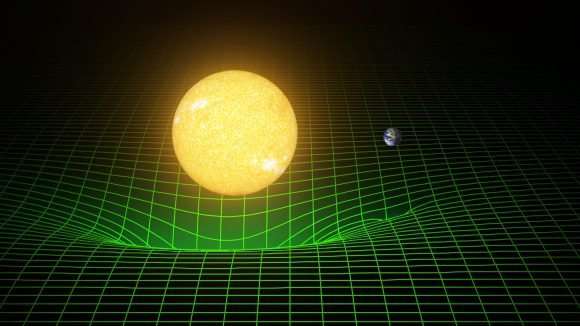

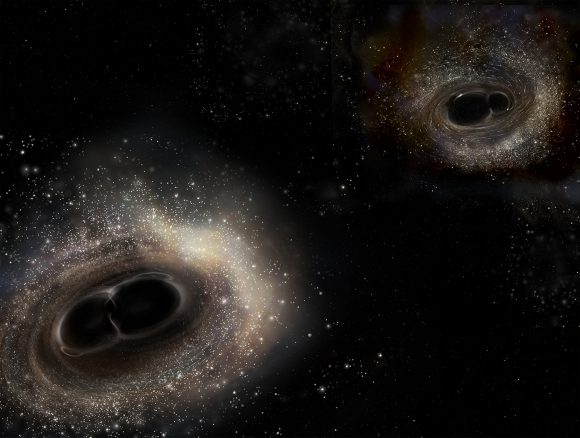

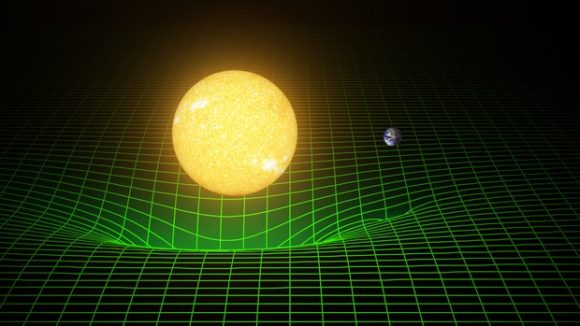

To put it simply, gravitational waves are ripples in space-time that are formed by major astronomical events – such as the merger of a binary black hole pair. They were first predicted over a century ago by Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, which indicated that massive perturbations would alter the structure of space-time. However, it was not until recent years that evidence of these waves was observed for the first time.

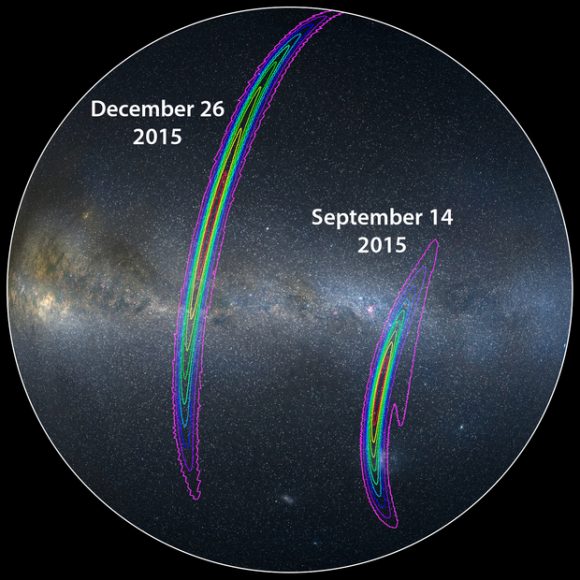

The first signal was detected by LIGO’s twin observatories – in Hanford, Washington, and Livingston, Louisiana, respectively – and traced to a black mole merger 1.3 billion light-years away. To date, four detections have been, all of which were due to the mergers of black-hole pairs. These took place on December 26, 2015, January 4, 2017, and August 14, 2017, the last being detected by LIGO and the European Virgo gravitational-wave detector.

For the role they played in this accomplishment, one half of the prize was awarded jointly to Caltech’s Barry C. Barish – the Ronald and Maxine Linde Professor of Physics, Emeritus – and Kip S. Thorne, the Richard P. Feynman Professor of Theoretical Physics, Emeritus. The other half was awarded to Rainer Weiss, Professor of Physics, Emeritus, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

As Caltech president Thomas F. Rosenbaum – the Sonja and William Davidow Presidential Chair and Professor of Physics – said in a recent Caltech press statement:

“I am delighted and honored to congratulate Kip and Barry, as well as Rai Weiss of MIT, on the award this morning of the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics. The first direct observation of gravitational waves by LIGO is an extraordinary demonstration of scientific vision and persistence. Through four decades of development of exquisitely sensitive instrumentation—pushing the capacity of our imaginations—we are now able to glimpse cosmic processes that were previously undetectable. It is truly the start of a new era in astrophysics.”

This accomplishment was all the more impressive considering that Albert Einstein, who first predicted their existence, believed gravitational waves would be too weak to study. However, by the 1960s, advances in laser technology and new insights into possible astrophysical sources led scientists to conclude that these waves might actually be detectable.

The first gravity wave detectors were built by Joseph Weber, an astrophysics from the University of Maryland. His detectors, which were built in the 1960s, consisted of large aluminum cylinders that would be driven to vibrate by passing gravitational waves. Other attempts followed, but all proved unsuccessful; prompting a shift towards a new type of detector involving interferometry.

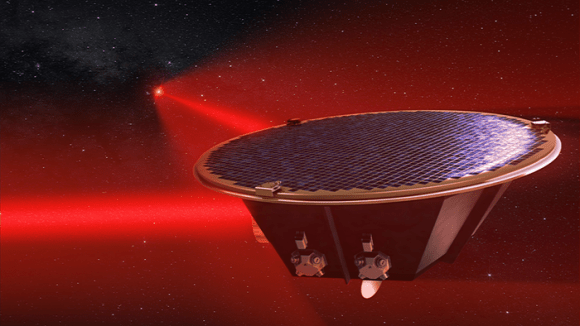

One such instrument was developed by Weiss at MIT, which relied on the technique known as laser interferometry. In this kind of instrument, gravitational waves are measured using widely spaced and separated mirrors that reflect lasers over long distances. When gravitational waves cause space to stretch and squeeze by infinitesimal amounts, it causes the reflected light inside the detector to shift minutely.

At the same time, Thorne – along with his students and postdocs at Caltech – began working to improve the theory of gravitational waves. This included new estimates on the strength and frequency of waves produced by objects like black holes, neutron stars and supernovae. This culminated in a 1972 paper which Throne co-published with his student, Bill Press, which summarized their vision of how gravitational waves could be studied.

That same year, Weiss also published a detailed analysis of interferometers and their potential for astrophysical research. In this paper, he stated that larger-scale operations – measuring several km or more in size – might have a shot at detecting gravitational waves. He also identified the major challenges to detection (such as vibrations from the Earth) and proposed possible solutions for countering them.

In 1975, Weiss invited Thorne to speak at a NASA committee meeting in Washington, D.C., and the two spent an entire night talking about gravitational experiments. As a result of their conversation, Thorne went back to Calteh and proposed creating a experimental gravity group, which would work on interferometers in parallel with researchers at MIT, the University of Glasgow and the University of Garching (where similar experiments were being conducted).

Development on the first interferometer began shortly thereafter at Caltech, which led to the creation of a 40-meter (130-foot) prototype to test Weiss’ theories about gravitational waves. In 1984, all of the work being conducted by these respective institutions came together. Caltech and MIT, with the support of the National Science Foundation (NSF) formed the LIGO collaboration and began work on its two interferometers in Hanford and Livingston.

The construction of LIGO was a major challenge, both logistically and technically. However, things were helped immensely when Barry Barish (then a Caltech particle physicist) became the Principal Investigator (PI) of LIGO in 1994. After a decade of stalled attempts, he was also made the director of LIGO and put its construction back on track. He also expanded the research team and developed a detailed work plan for the NSF.

As Barish indicated, the work he did with LIGO was something of a dream come true:

“I always wanted to be an experimental physicist and was attracted to the idea of using continuing advances in technology to carry out fundamental science experiments that could not be done otherwise. LIGO is a prime example of what couldn’t be done before. Although it was a very large-scale project, the challenges were very different from the way we build a bridge or carry out other large engineering projects. For LIGO, the challenge was and is how to develop and design advanced instrumentation on a large scale, even as the project evolves.”

By 1999, construction had wrapped up on the LIGO observatories and by 2002, LIGO began to obtain data. In 2008, work began on improving its original detectors, known as the Advanced LIGO Project. The process of converting the 40-m prototype to LIGO’s current 4-km (2.5 mi) interferometers was a massive undertaking, and therefore needed to be broken down into steps.

The first step took place between 2002 and 2010, when the team built and tested the initial interferometers. While this did not result in any detections, it did demonstrate the observatory’s basic concepts and solved many of the technical obstacles. The next phase – called Advanced LIGO, which took placed between 2010 and 2015 – allowed the detectors to achieve new levels of sensitivity.

These upgrades, which also happened under Barish’s leadership, allowed for the development of several key technologies which ultimately made the first detection possible. As Barish explained:

“In the initial phase of LIGO, in order to isolate the detectors from the earth’s motion, we used a suspension system that consisted of test-mass mirrors hung by piano wire and used a multiple-stage set of passive shock absorbers, similar to those in your car. We knew this probably would not be good enough to detect gravitational waves, so we, in the LIGO Laboratory, developed an ambitious program for Advanced LIGO that incorporated a new suspension system to stabilize the mirrors and an active seismic isolation system to sense and correct for ground motions.”

Given how central Thorne, Weiss and Barish were to the study of gravitational waves, all three were rightly-recognized as this year’s recipients of the Nobel Prize in Physics. Both Thorne and Barish were notified that they had won in the early morning hours on October 3rd, 2017. In response to the news, both scientists were sure to acknowledge the ongoing efforts of LIGO, the science teams that have contributed to it, and the efforts of Caltech and MIT in creating and maintaining the observatories.

“The prize rightfully belongs to the hundreds of LIGO scientists and engineers who built and perfected our complex gravitational-wave interferometers, and the hundreds of LIGO and Virgo scientists who found the gravitational-wave signals in LIGO’s noisy data and extracted the waves’ information,” said Thorne. “It is unfortunate that, due to the statutes of the Nobel Foundation, the prize has to go to no more than three people, when our marvelous discovery is the work of more than a thousand.”

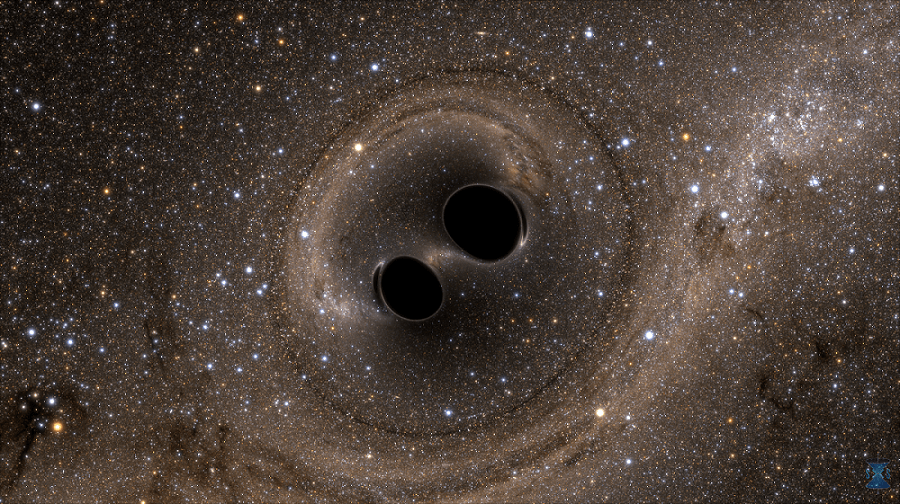

“I am humbled and honored to receive this award,” said Barish. “The detection of gravitational waves is truly a triumph of modern large-scale experimental physics. Over several decades, our teams at Caltech and MIT developed LIGO into the incredibly sensitive device that made the discovery. When the signal reached LIGO from a collision of two stellar black holes that occurred 1.3 billion years ago, the 1,000-scientist-strong LIGO Scientific Collaboration was able to both identify the candidate event within minutes and perform the detailed analysis that convincingly demonstrated that gravitational waves exist.”

Looking ahead, it is also pretty clear that Advanved LIGO, Advanced Virgo and other gravitational wave observatories around the world are just getting started. In addition to having detected four separate events, recent studies have indicated that gravitational wave detection could also open up new frontiers for astronomical and cosmological research.

For instance, a recent study by a team of researchers from the Monash Center for Astrophysics proposed a theoretical concept known as ‘orphan memory’. According to their research, gravitational waves not only cause waves in space-time, but leave permanent ripples in its structure. By studying the “orphans” of past events, gravitational waves can be studied both as they reach Earth and long after they pass.

In addition, a study was released in August by a team of astronomers from the Center of Cosmology at the University of California Irvine that indicated that black hole mergers are far more common than we thought. After conducting a survey of the cosmos intended to calculate and categorize black holes, the UCI team determined that there could be as many as 100 million black holes in the galaxy.

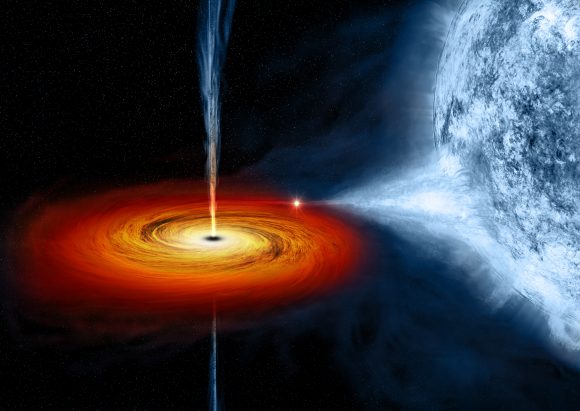

Another recent study indicated that the Advanced LIGO, GEO 600, and Virgo gravitational-wave detector network could also be used to detect the gravitational waves created by supernovae. By detecting the waves created by star that explode near the end of their lifespans, astronomers could be able to see inside the hearts of collapsing stars for the first time and probe the mechanics of black hole formation.

The Nobel Prize in Physics is one of the highest honors that can be bestowed upon a scientist. But even greater than that is the knowledge that great things resulted from one’s own work. Decades after Thorne, Weiss and Barish began proposing gravitational wave studies and working towards the creation of detectors, scientists from all over the world are making profound discoveries that are revolutionizing the way we think of the Universe.

And as these scientists will surely attest, what we’ve seen so far is just the tip of the iceberg. One can imagine that somewhere, Einstein is also beaming with pride. As with other research pertaining to his theory of General Relativity, the study of gravitational waves is demonstrating that even after a century, his predictions were still bang on!

And be sure to check out this video of the Caltech Press Conference where Barish and Thorn were honored for their accomplishments: