Look at those astronauts, flying through space without a care in the world. But how can they be floating when there’s gravity pulling at them in every direction?

Hey look! It’s a montage of adorable astronauts engaging in hilarious space stuff in zero gravity. Look at them throwing bananas, playing Bowie songs, drinking floating juice balls, and generally having a gay old time in the weightlessness of deep space. It’s a camera inside a ball of water, you won’t believe what happens next! Or whatever it was they told you to get you to click that video.

Space isn’t all that far away, in fact, it’s likely closer than the next big city over. We have an equation to calculate gravitational pull between objects in space. It’s this little monster right here. It’s the “r” at the bottom we’re interested in here. When it’s a small value, like the short 370 km above your head there’s no remarkable difference between being on the space station or being on the surface. In fact, our beloved astronauts experience about 90% of the Earth’s gravity.

So why are they floating around so effortlessly in a most peculiar way? Shouldn’t they fall to the bottom of the space station? Shouldn’t the whole space station crash to the ground. Quickly, to the internet for our dramatic and creepy twilight zone style ending when we realize that the book was actually titled “How to cook forty humans!”. We have to tell someone!

According to our math those astronauts aren’t floating, they’re falling. THEY’RE FALLING.

And roll credits…So, the real twist was that NASA knew this all along. What looks like zero gravity is actually weightlessness. And you can get weightlessness whenever you’re falling.

You know that feeling when you crest a hill on a rollercoaster, or just as the elevator starts moving down? That’s you experiencing decreased weight. Jump out of an airplane, and you’ll experience seconds or even a minute of weightlessness before you have to open the chute. But the Earth moving towards you too rapidly for a little dirt-and-rock-cuddle-spooning time reminds you that this is falling, not flying.

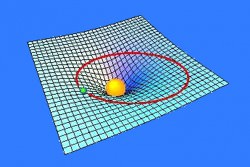

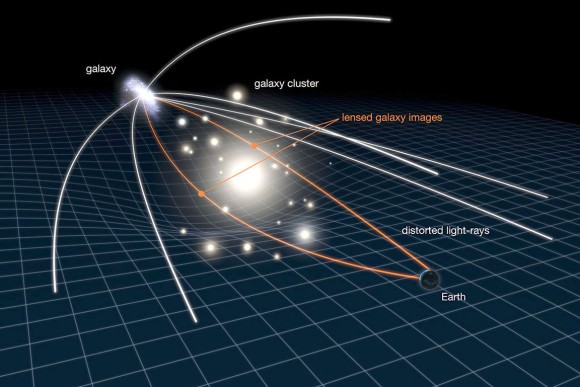

Astronauts are orbiting Earth at a speed of 28,000 kilometers per hour, completing one spin around the planet every 90 minutes. As the astronauts accelerate towards our planet, the curvature of the Earth falls away from them – so they never actually slam into a horrible fiery twisted metal pancake of death.

Imagine there was a tower 370 km high. If you jumped off the top of the tower, you’d fall to the ground, near the base of the tower with a splat. Now, imagine if you jumped sideways off the tower. You might land a few kilometers away from the base of the tower. But still hit the ground. Now, imagine if you could run sideways at 28,000 km/h and you leap off the side of the tower. You’d still be falling, but the Earth is falling away at exactly the same rate, so you never actually hit the ground.

Despite years of training, many astronauts get motion sickness when they first arrive in orbit, and it can take a few days for them to become accustomed to the sensation.… And nobody judges them because they have the giant brass ones required to go into space in the first place.

NASA has developed a special aircraft to help astronauts get experience with weightlessness. It’s called the KC 135, it flies in the emperor of barfolpolis-inducing parabolas, and has the nickname “The Vomit Comet”. At the top of each parabola, the passengers of the KC 135 get to experience a few seconds of weightlessness before gravity catches up with them again and they fall down on the floor of the aircraft, followed with the experience of double gravity on the bottom of the parabola.

Then it’s upchuck city, or everyone takes a few moments to talk to ralph on the big white phone, or has a brief episode of the Technicolor-face-shouts-double-rainbarf across the sky.

What does it mean? What I’m saying is the vomit flows like a river.

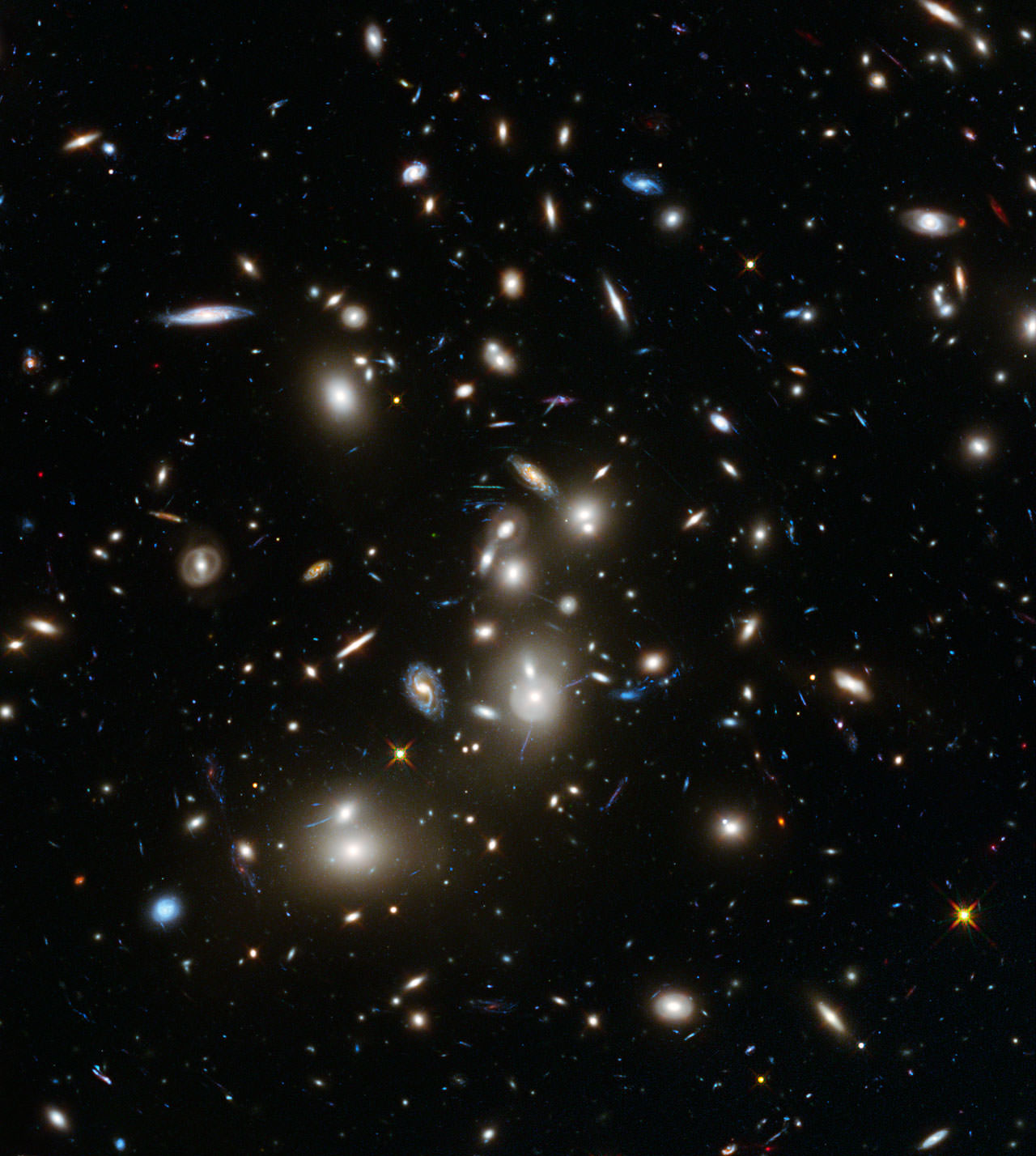

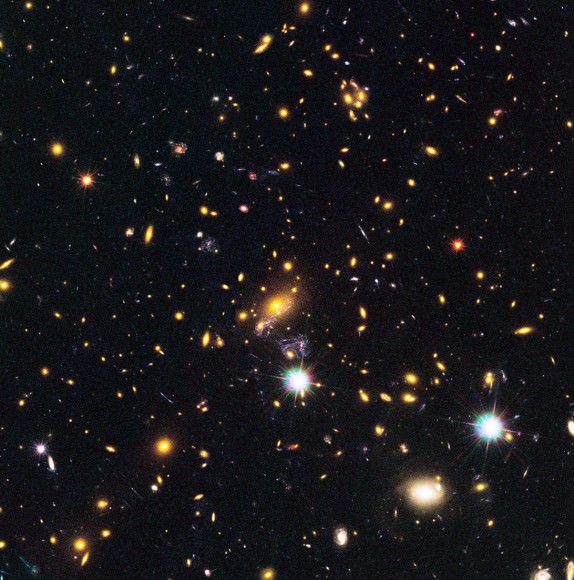

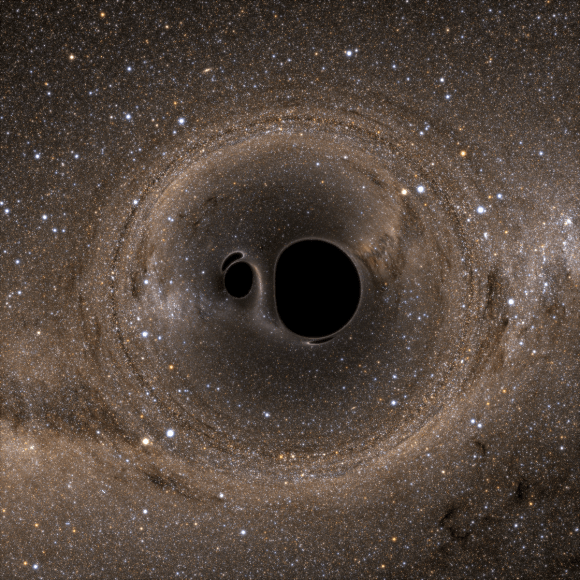

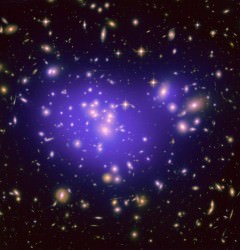

In fact, there is no place you could go in the entire Universe where you could be in true zero gravity. Ever. At all. None. As we discussed in a previous episode, you’re under the influence of gravity of every single atom in the observable Universe. Without the Earth or the Sun here, you’d start falling into the center of the Milky Way. Or maybe into the Virgo Supercluster.

We’re all falling all the time. Fortunately we’re stuck to a giant ball which gives us a reference point where everything falls at the same rate we do including our atmosphere and lunch, both prior to and post consumption.

To best illustrate our point, I’m going to turn to Douglas Adams. He said in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy series: “the knack of flying is learning how to throw yourself at the ground and miss.” Do you want to experience true weightlessness? Would you be willing to go to orbit and give it a try?