Gravity. The average person probably doesn’t think about it on a daily basis, but yet gravity affects our every move. Because of gravity, we fall down (not up), objects crash to the floor, and we don’t go flying off into space when we jump in the air. The old adage, “everything that goes up must come down” makes perfect sense to everyone because from the day we are born, we are seemingly bound to Earth’s surface due to this all-pervasive invisible force.

But physicists think about gravity all the time. To them, gravity is one of the mysteries to be solved in order to get a complete understanding of how the Universe works.

So, what is gravity and where does it come from?

To be honest, we’re not entirely sure.

We know from Isaac Newton and his law of gravitation that any two objects in the Universe exert a force of attraction on each other. This relationship is based on the mass of the two objects and the distance between them. The greater the mass of the two objects and the shorter the distance between them, the stronger the pull of the gravitational forces they exert on each other.

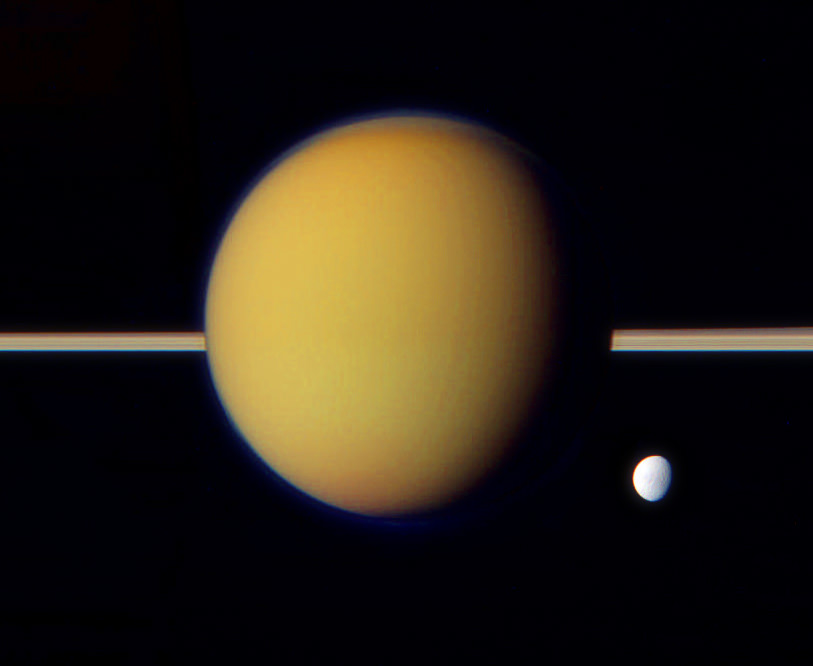

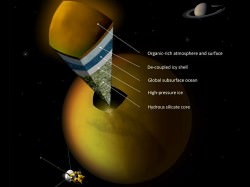

We also know that gravity can work in a complex system with several objects. For example, in our own Solar System, not only does the Sun exert gravity on all the planets, keeping them in their orbits, but each planet exerts a force of gravity on the Sun, as well as all the other planets, too, all to varying degrees based on the mass and distance between the bodies. And it goes beyond just our Solar System, as actually, every object that has mass in the Universe attracts every other object that has mass — again, all to varying degrees based on mass and distance.

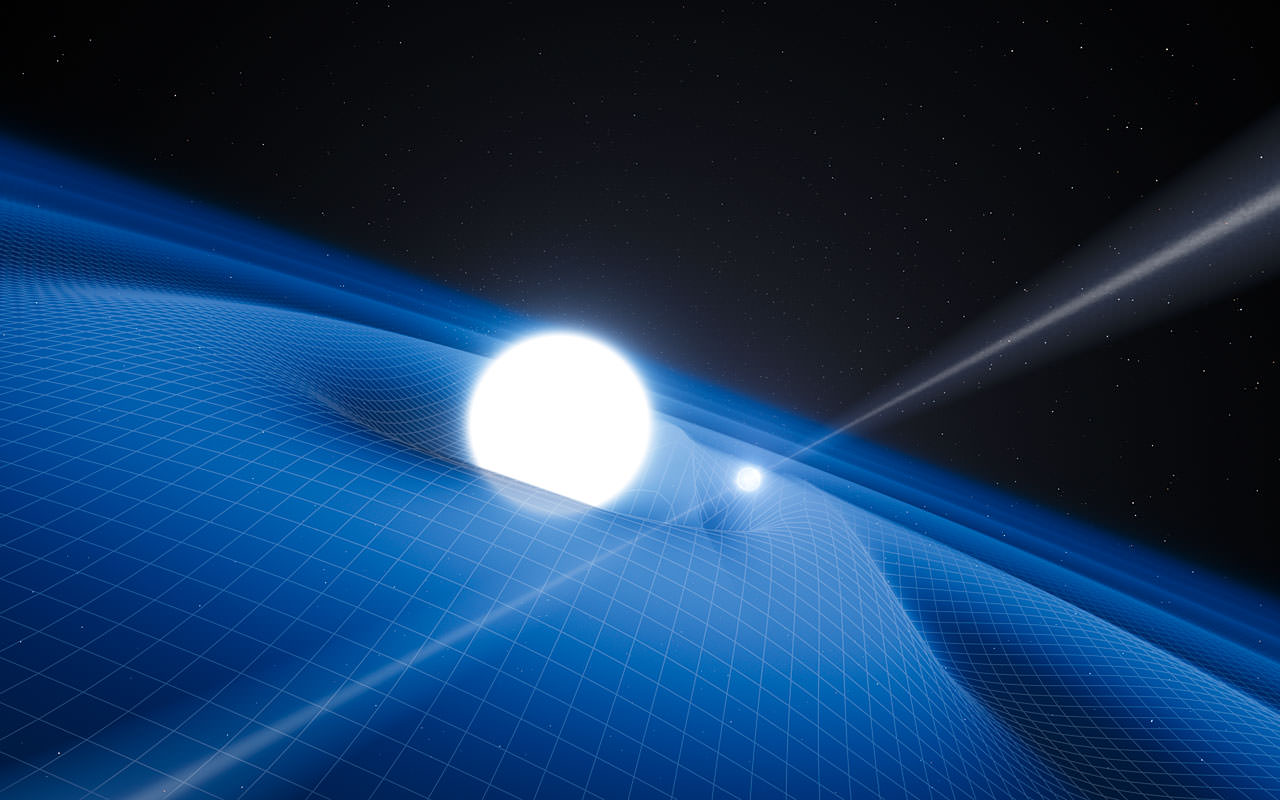

With his theory of relativity, Albert Einstein explained how gravity is more than just a force: it is a curvature in the space-time continuum. That sounds like something straight out of science fiction, but simply put, the mass of an object causes the space around it to essentially bend and curve. This is often portrayed as a heavy ball sitting on a rubber sheet, and other smaller balls fall in towards the heavier object because the rubber sheet is warped from the heavy ball’s weight.

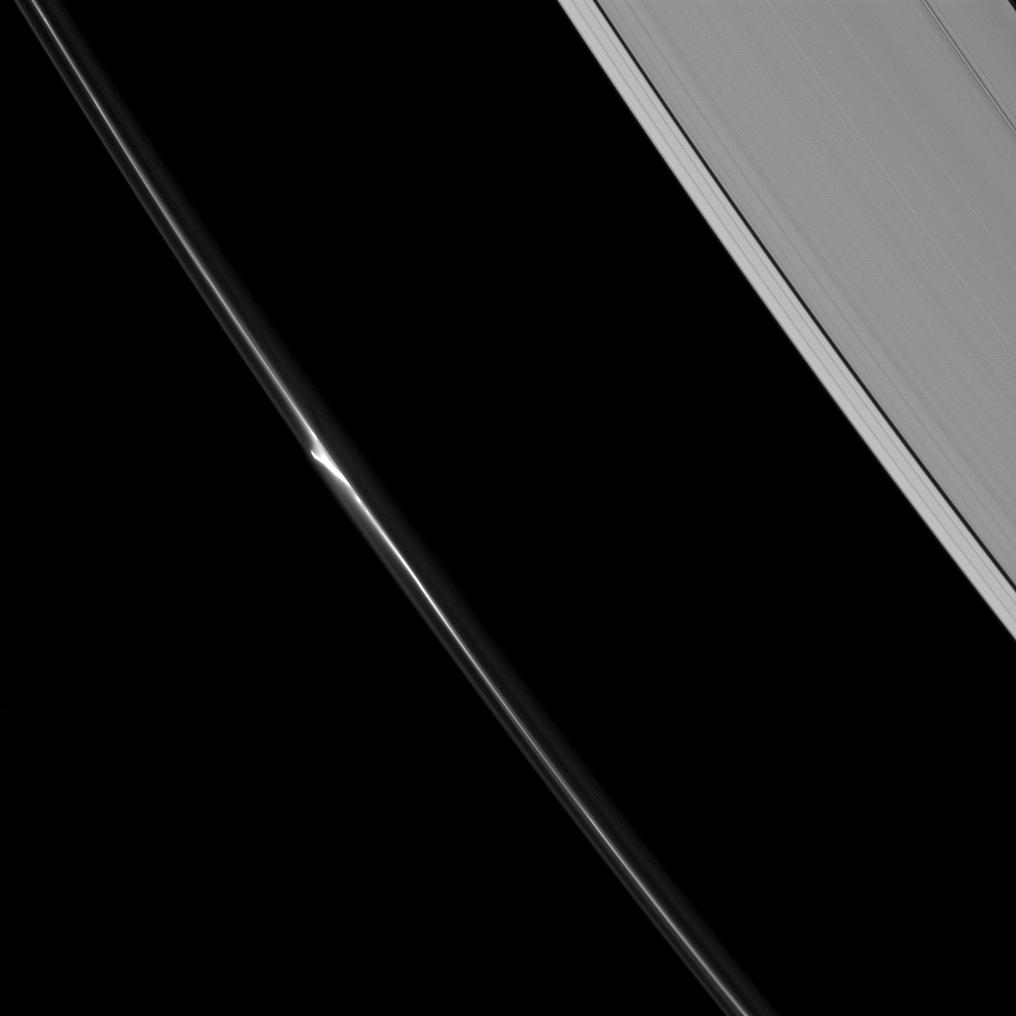

In reality, we can’t see curvature of space directly, but we can detect it in the motions of objects. Any object ‘caught’ in another celestial body’s gravity is affected because the space it is moving through is curved toward that object. It is similar to the way a coin would spiral down one of those penny slot cyclone machines you see at tourist shops, or the way bicycles spiral around a velodrome.

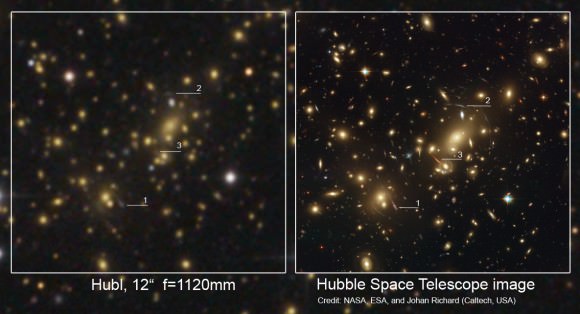

We can also see the effects of gravity on light in a phenomenon called gravitational lensing. If an object in space is massive enough – such as a large galaxy or cluster of galaxies — it can cause an otherwise straight beam of light to curve around it, creating a lensing effect.

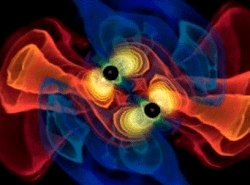

But these effects – where there are basically curves, hills and valleys in space — occur for reasons we can’t fully really explain. Besides being a characteristic of space, gravity is also a force (but it is the weakest of the four forces), and it might be a particle, too. Some scientists have proposed particles called gravitons cause objects to be attracted to one another. But gravitons have never actually been observed. Another idea is that gravitational waves are generated when an object is accelerated by an external force, but these waves have never been directly detected, either.

Our understanding of gravity breaks down at both the very small and the very big: at the level of atoms and molecules, gravity just stops working. And we can’t describe the insides of black holes and the moment of the Big Bang without the math completely falling apart.

The problem is that our understanding of both particle physics and the geometry of gravity is incomplete.

“Having gone from basically philosophical understandings of why things fall to mathematical descriptions of how things accelerate down inclines from Galileo, to Kepler’s equations describing planetary motion to Newton’s formulation of the Laws of Physics, to Einstein’s formulations of relativity, we’ve been building and building a more comprehensive view of gravity. But we’re still not complete,” said Dr. Pamela Gay. “We know that there still needs to be some way to unite quantum mechanics and gravity and actually be able to write down equations that describe the centers of black holes and the earliest moments of the Universe. But we’re not there yet.”

And so, the mystery remains … for now.

This “Minute Physics” video helps explain what we know about gravity:

We have written many articles about gravity for Universe Today. Here’s an article about gravity and antimatter, and here’s an article about the discovery of gravity. This recent article discusses how the latest research looks at quantum physics to explain gravity.

If you’d like more info on Gravity, check out The Constant Pull of Gravity: How Does It Work?, and here’s a link to Gravity on Earth Versus Gravity in Space: What’s the Difference?.

We’ve also recorded an entire episode of Astronomy Cast all about Gravity. Listen here, Episode 102: Gravity.

For further reading:

Cornell Astronomy

UT-Knoxville