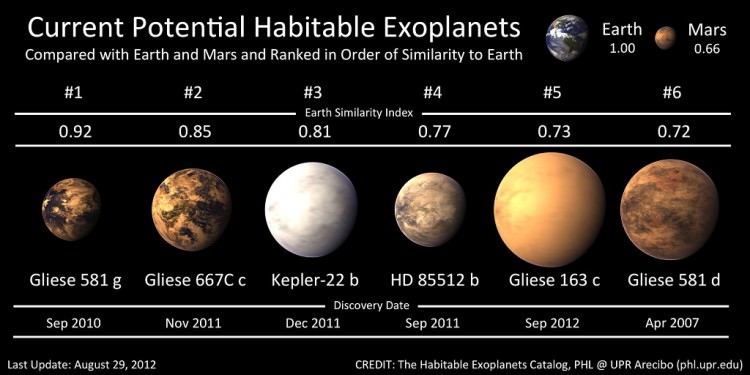

Artistic representation of the current five known potential habitable worlds. Will this list broaden under a new habitability model? Credit: The Planetary Habitability Laboratory (PHL)

When we think of life on other planets, we tend to imagine things (microbes, plant life and yes, humanoids) that exist on the surface. But Earth’s biosphere doesn’t stop at the planet’s surface, and neither would life on another world, says a new study that expands the so-called ‘Goldilocks Zone’ to include the possibility of subterranean habitable zones. This new model of habitability could vastly increase where we could expect to find life, as well as potentially increasing the number of habitable exoplanets.

We know that a large fraction of the Earth’s biomass is dwelling down below, and recently microbiologists discovered bacterial life, 1.4 kilometers below the sea floor in the North Atlantic, deeper in the Earth’s crust than ever before. This and other drilling projects have brought up evidence of hearty microbes thriving in deep rock sediments. Some derive energy from chemical reactions in rocks and others feed on organic seepage from life on the surface. But most life requires at least some form of water.

“Life ‘as we know it’ requires liquid water,” said Sean McMahon, a PhD student from the University of Aberdeen’s (Scotland) School of Geosciences. “Traditionally, planets have been considered ‘habitable’ if they are in the ‘Goldilocks zone’. They need to be not too close to their sun but also not too far away for liquid water to persist, rather than boiling or freezing, on the surface. However, we now know that many micro-organisms—perhaps half of all living things on Earth—reside deep in the rocky crust of the planet, not on the surface.”

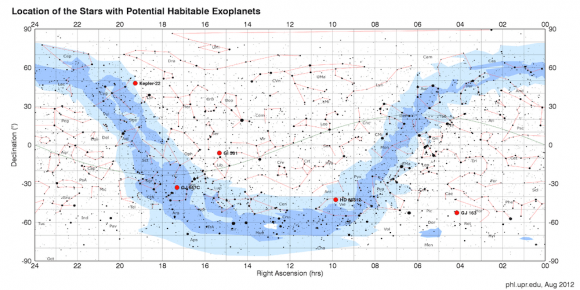

Location in the night sky of the stars with potential habitable exoplanets (red circles). There are two in Gliese 581. Click the image for larger version. CREDIT: PHL @ UPR Arecibo and Jim Cornmell.

While suns warm planet surfaces, there’ also heat from the planets’ interiors. Crust temperature increases with depth so planets that are too cold for liquid water on the surface may be sufficiently warm underground to support life.

“We have developed a new model to show how ‘Goldilocks zones’ can be calculated for underground water and hence life,” McMahon said. “Our model shows that habitable planets could be much more widespread than previously thought.”

In the past, the Goldilocks zone has really been determined by a circumstellar habitable zone (CHZ), which is a range of distances from a star, and depending on the star’s characteristics, the zone varies. The consensus has been that planets that form from Earth-like materials within a star’s CHZ are able to maintain liquid water on their surfaces.

But McMahon and his professor, John Parnell, also from Aberdeen University who is leading the study now are introducing a new term: subsurface-habitability zone (SSHZ). This denote the range of distances from a star within which planets are habitable at any depth below their surfaces up to a certain maximum, for example, they mentioned a “SSHZ for 2 km depth”, within which planets can support liquid water 2 km or less underground.

If this notion catches on – which it should – it will have exoplanet hunters recalculating the amount of potentially habitable worlds.

The research was presented at the annual British Science Festival in Aberdeen.

Source: University of Aberdeen