In the past decade, the rate at which extra-solar planets have been discovered and characterized has increased prodigiously. Because of this, the question of when we might explore these distant planets directly has repeatedly come up. In addition, the age-old question of what we might find once we get there – i.e. is humanity alone in the Universe or not? – has also come up with renewed vigor.

These questions have led to a number of interesting and ambitious proposals. These include Project Blue, a space telescope which would directly observe any planets orbiting Alpha Centauri, and Breakthrough Starshot – which aims to send a laser-driven nanocraft to Alpha Centauri in just 20 years. But perhaps the most daring proposal comes in the form of Project Genesis, which would attempt to seed distant planets with life.

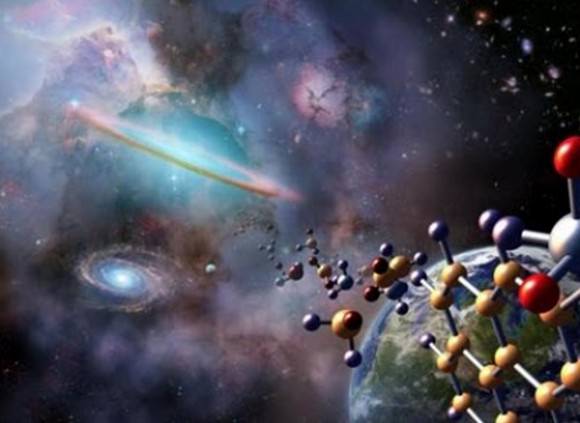

This proposal was put forth by Dr. Claudius Gros, a theoretical physicist from the Institute for Theoretical Physics at Goethe University Frankfurt. In 2016, he published a paper that described how robotic missions equipped with gene factories (or cryogenic pods) could be used to distribute microbial life to “transiently habitable exoplanets – i.e. planets capable of supporting life, but not likely to give rise to it on their own.

Not long ago, Universe Today wrote about Dr. Gros’ recent study where he proposed using a magnetic sail to slow down an interstellar spacecraft. We were fortunate to catch up with Dr. Gros again and had a chance to ask him about Project Genesis. You can find our Q&A below, and be sure to check out his seminal paper that describes this project – “Developing Ecospheres on Transiently Habitable Planets: The Genesis Project“.

Exoplanets come in all sizes, temperatures and compositions. The purpose of the Genesis project is to offer terrestrial life alternative evolutionary pathways on those exoplanets that are potentially habitable but yet lifeless. The basic philosophy of most scientists nowadays is that simple life is common in the universe and complex life is rare. We don’t know that for sure, but at the moment, that is the consensus.

If you had good conditions, simple life can develop very fast, but complex life will have a hard time. At least on Earth, it took a very long time for complex life to arrive. The Cambrian Explosion only happened about 500 million years ago, roughly 4 billion years after Earth was formed. If we give planets the opportunity to fast forward evolution, we can give them the chance to have their own Cambrian Explosions.

What worlds would be targeted?

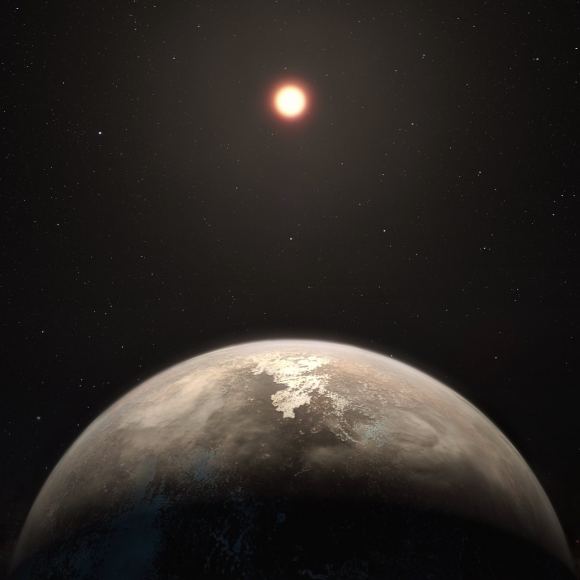

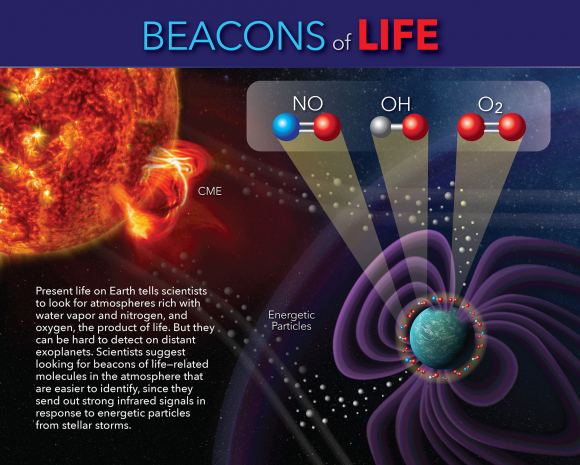

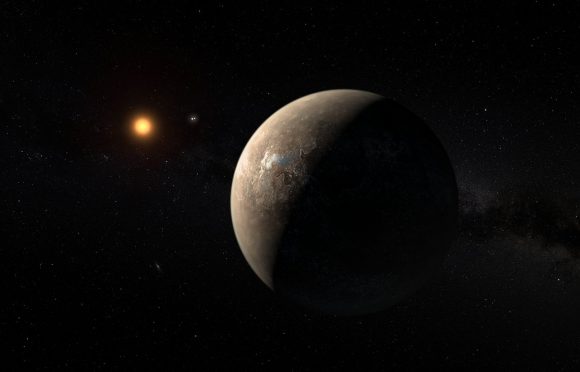

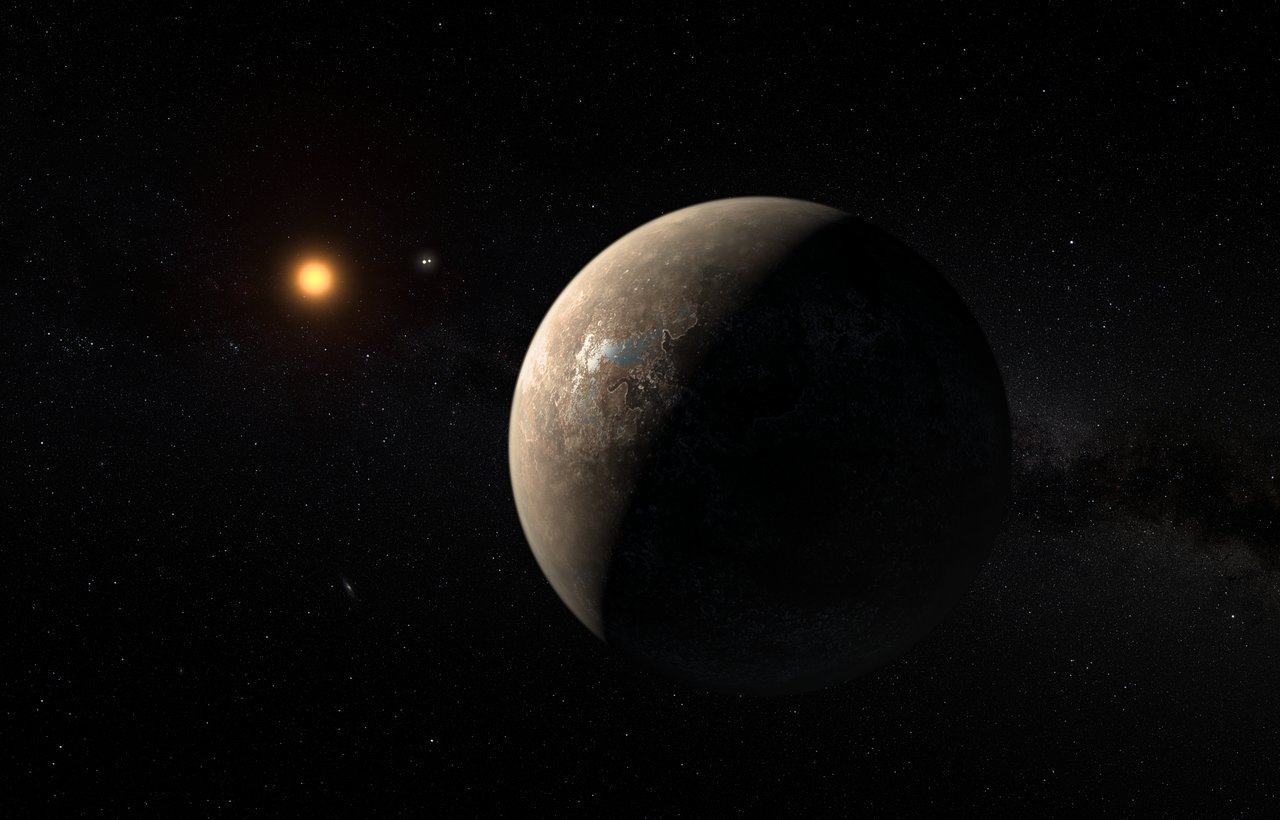

The prime candidates are habitable “oxygen planets” around M-dwarfs like TRAPPIST-1. It is very likely that the oxygen-rich primordial atmosphere of these planets will have prevented abiogenesis in first place, that is the formation of life. Our galaxy could potentially harbor billions of habitable but lifeless oxygen planets.

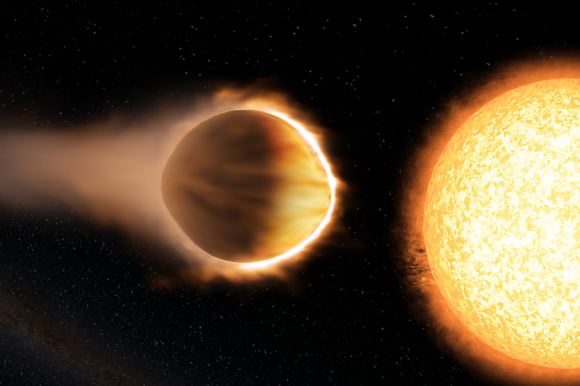

Nowadays, astronomers are looking for planets around M-stars. These are very different from planets around Sun-like stars. Once a star forms, it takes a certain amount of time to contract to the point where fusion begins, and it starts to produce energy. For the Sun, this took 10 million years, which is very fast. For stars like TRAPPIST-1, it would take 100 million to 1 billion years. Then they have to contract to dissipate their initial heat.

The planets around TRAPPIST-1 would have been very hot, because the star was very hot for a long time. All the water that was in their stratospheres, the UV radiation would have disassociated it into hydrogen and oxygen – the hydrogen escaped, and the oxygen remained. All surveys have showed that they have oxygen atmospheres, but this is the product of chemical disassociation and not from plants (as with Earth).

There’s a good chance that oxygen planets are sterile, because oxygen planets eat up prebiotic conditions. We believe there may be billions of oxygen planets in our galaxy. They would have no life, and complex life needs oxygen. In science fiction, you have all these planets that look alike. We could imagine that in half a billion years, we could have this because we seeded oxygen planets (only we couldn’t travel there quickly since we have no FTL).

What kind of organisms would be sent?

The first wave would consist of unicellular autotrophs. That is photo-synthesizing bacteria, like cyanobacteria, and eukaryotes (the cell type making up all complex life, that is animals and plants). Heterotrophs would follow in a second stage, organisms that feed on other organisms and can only exist after autotrophs exist and take root.

How would these organisms be sent?

That depends on the technology. If it can advance, we can miniaturize a gene factory. In principle, nature is a miniature gene factory. Everything we want to produce is very small. If it’s possible that would be the best option. Send in a gene bank, and then select the most optimal organism to send down. If that is not possible, you would have to have frozen germs. In the end, it depends on what would be the technically available.

You could also send in synthetic life. Synthetic biology is a very active research field, which involves reprogramming the genetic code. In science fiction, you have alien life with a different genetic code. Today, people are trying to produce this here on Earth. The end goal is to have new life forms that are based on a different code. This would be very dangerous on Earth, but on a far-distant planet, it would be beneficial.

What if these worlds are not sterile?

Genesis is all about life, not destroying life, so we’d want to avoid that. The probes would have to go into orbit, so we are pretty sure that from orbit, we could detect complex life on the surface. The Genesis Project was intended for planets that are not habitable for eternity. Earth is habitable for billions of years, but we are not sure about habitable exoplanets.

Exoplanets come in all kinds of sized, temperatures, and habitabilities. Many of these planets will only be habitable for some time, maybe 1 billion years. Life there will not have time to evolve into complex life forms. So you have a decision: leave them like they are, or take a chance at developing complex life there.

Some believe that all bacteria are worth saving. On Earth, there is no protection for bacteria. But bacteria living on different planets are treated differently. Planetary protection, why do we do that? So we can study the life, or for the sake of protecting life itself? Mars most likely had life at one time, but now not, except for maybe a few bacteria. Still, we plan manned missions to Mars, which means planetary protection is off. It’s a contradiction.

I am very enthusiastic about finding life, but what about the planets where we don’t find life? This offers the possibility about doing something about it.

Could humanity benefit from this someday (i.e. colonize “seeded” planets)?

Yes and no. Yes, because nothing would keep our decedents (or any other intelligence living on Earth by then), to visit Genesis planets in 10-100 million years (the minimal time for the life initially seeded to fully unfold). No, because the involved time spans are so long, that it is not rational to speak of a ‘benefit’.

How soon could such a mission be mounted?

Genesis probes could be launched by the same directed-energy launch system planned for the Breakthrough Starshot initiative. Breakthrough Starshot aims to send very fast, very small, very light probes of about 1 gram to another star system. The same laser technology could send something more massive, but slower. Slow is relative, of course. So the in the end it depends on what is optimal.

The magnetic sail paper I recently wrote was a sample mission to show that it was possible. The probe would be about the size of a car (1 tonne) and would travel at a speed of about 1000 km/s – slow for interstellar travel relative to speed of light, but fast for Earth. If you reduce the velocity by a factor of 100, the mass you can propel is 10,000 heavier. You could accelerate a 1-tonne Genesis Probe and it would still fit into the layout of Breakthrough Starshot.

Therefore, the launch facility could see dual use and you wouldn’t need to build something new. Once that is in place one would need to test the magnetic sail. A realistic time span would hence be in the 50-100 years window.

What counter-arguments are there against this?

There are three main lines of counter-arguments. The first is the religious counter-argument, which says that humanity should not play God. The Genesis project is however not about creating life, but to give life the possibility to further develop. Just not on Earth, but elsewhere in the cosmos.

The second is the Planetary protection argument, which argues that we should not interfere. Some people objecting to the Genesis Project cite the ‘first directive’ of the Star Trek TV series. The Genesis Project fully supports planetary protection of planets which harbor complex life and of planets on which complex life could potentially develop in the future. The Genesis project will target only planets on which complex life could not develop on its own.

The third argument is about the lack of benefit to humanity. The Genesis Project is expressively not for human benefit. It is reasonable to argue, from the perspective of survival, that the ethical values of a species (like humanity) has to put the good of the species at the center. Ethical is therefore “what is good for our own species”. Spending a large amount of money on a project, like the Genesis Project, which is expressively not for the benefit of our own species, would then be unethical.

___

Our thanks go out to Dr. Gros for taking the time to talk to us! We hope to hear more from him in the future and wish him the best of luck with Project Genesis.