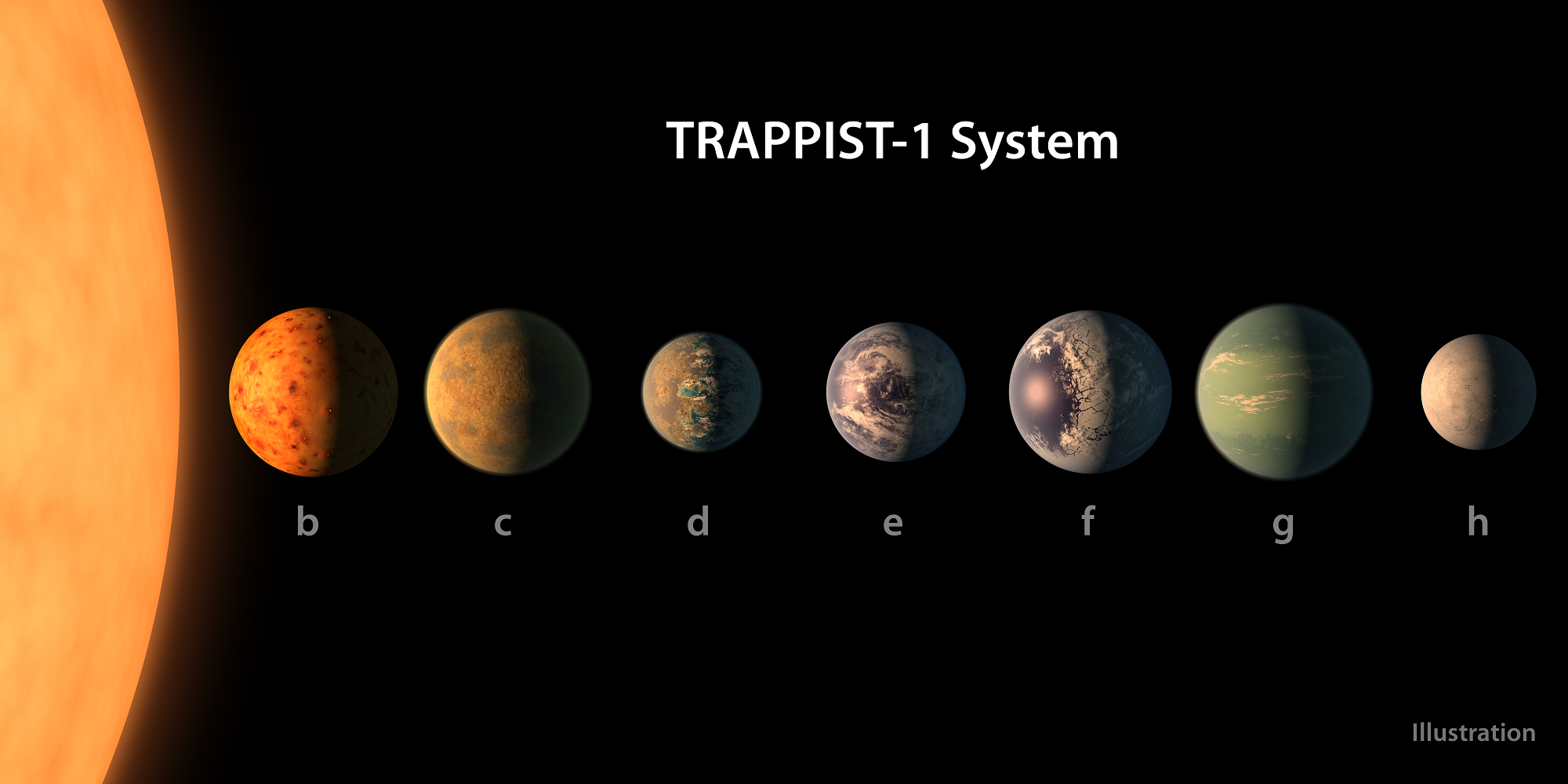

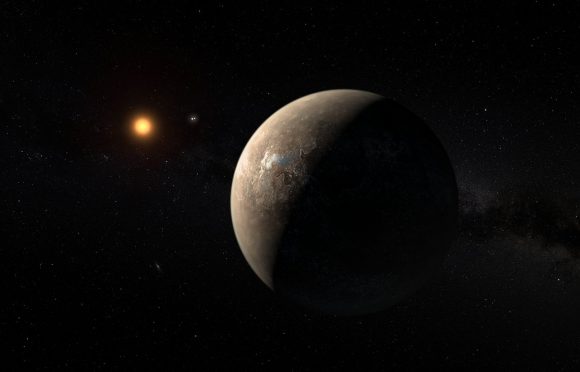

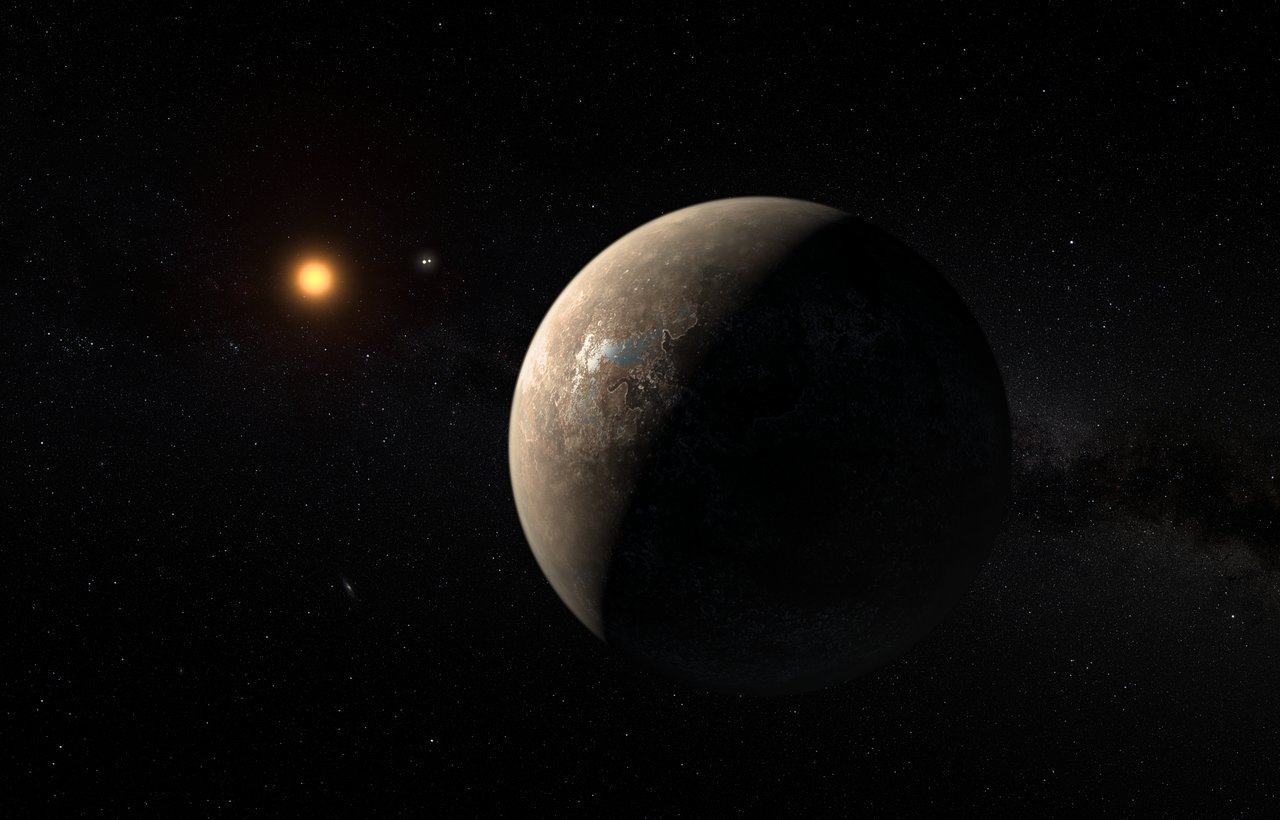

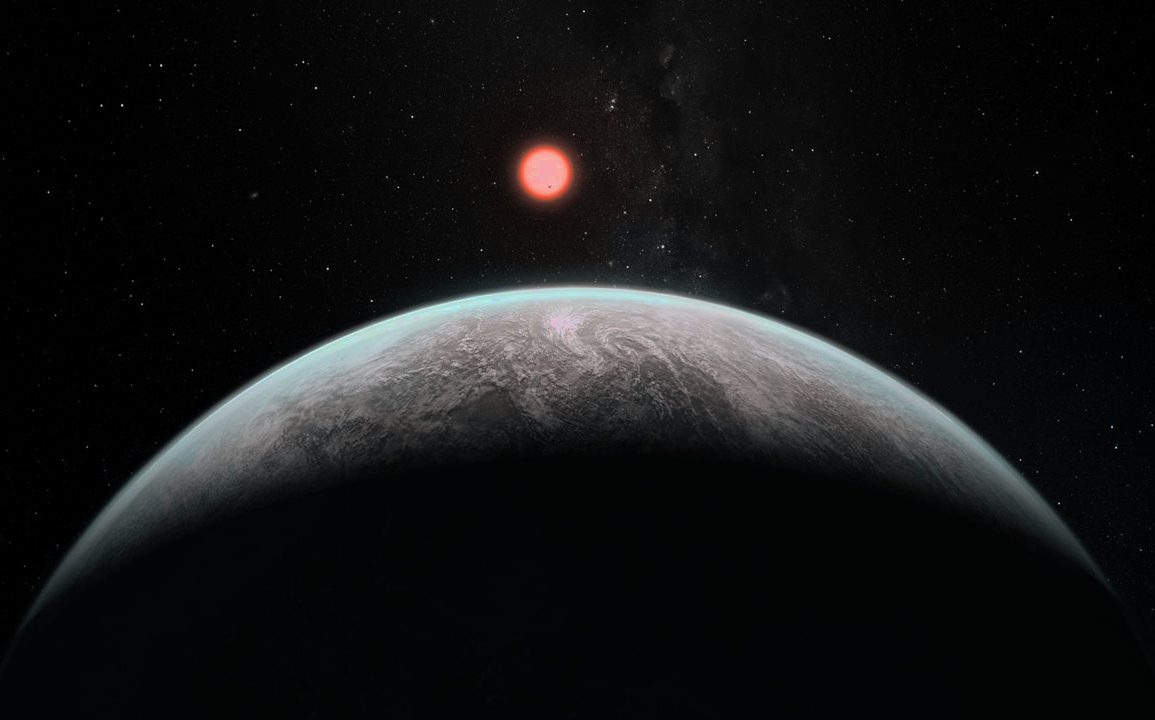

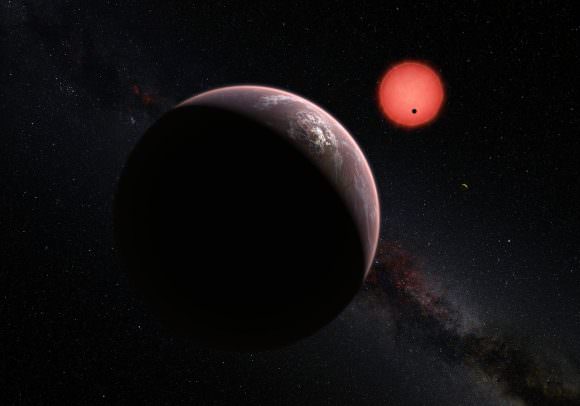

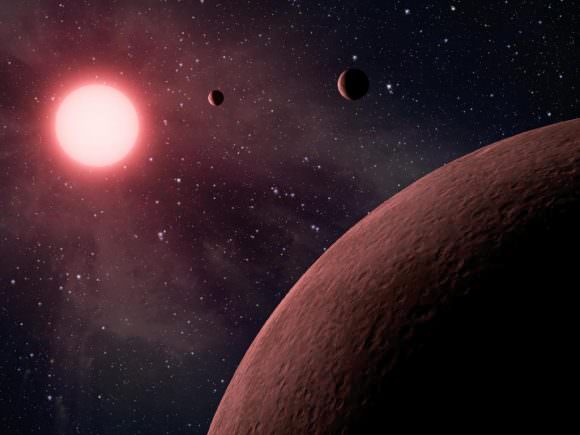

M-type stars, also known as “red dwarfs”, have become a popular target for exoplanet hunters of late. This is understandable given the sheer number of terrestrial (i.e. rocky) planets that have been discovered orbiting around red dwarf stars in recent years. These discoveries include the closest exoplanet to our Solar System (Proxima b) and the seven planets discovered around TRAPPIST-1, three of which orbit within the star’s habitable zone.

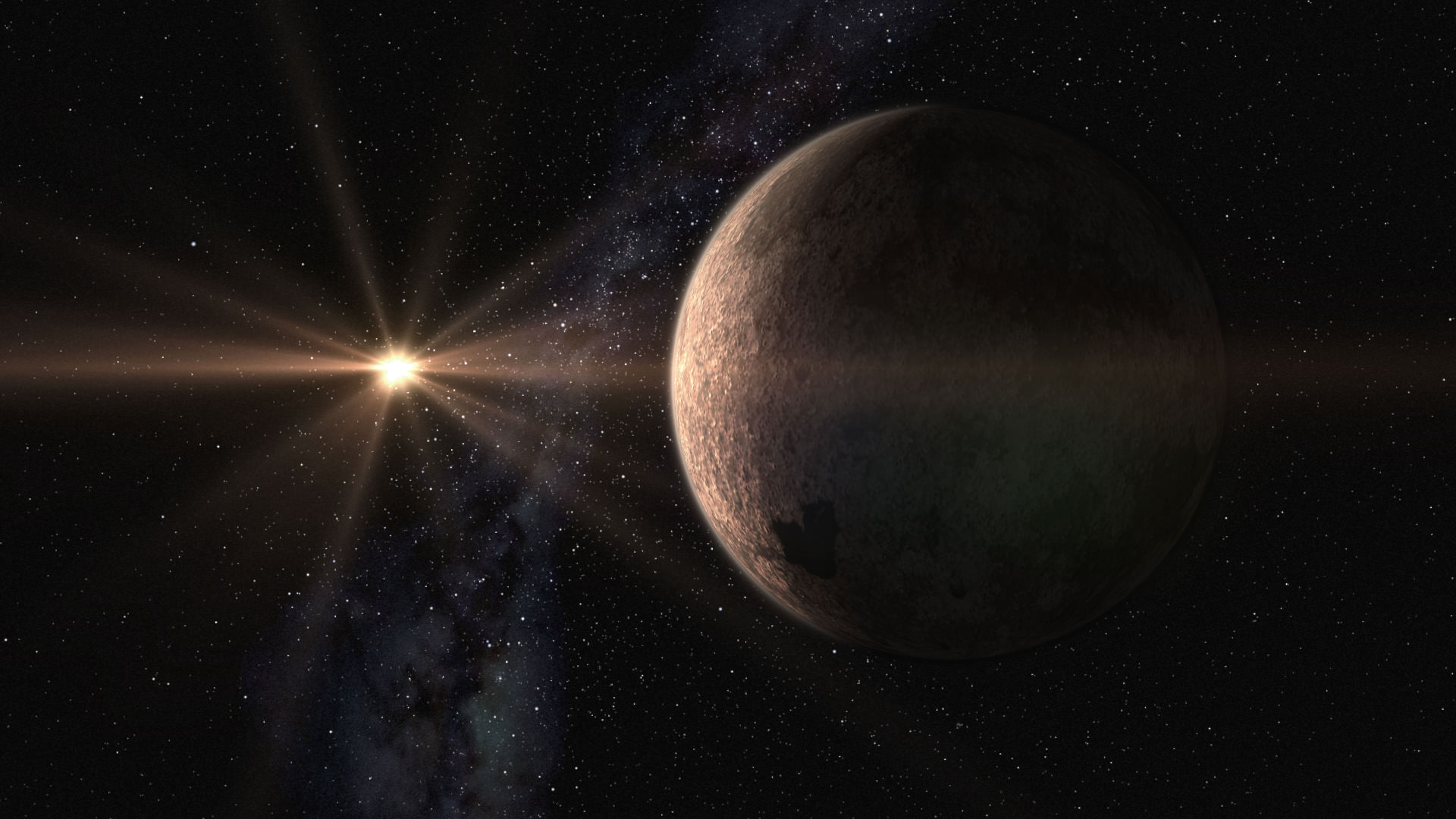

The latest find comes from a team of international astronomers who discovered a planet around GJ 625, a red dwarf star located just 21 light years away from Earth. This terrestrial planet is roughly 2.82 times the mass of Earth (aka. a “super-Earth”) and orbits within the star’s habitable zone. Once again, news of this discovery is prompting questions about whether or not this world could indeed be habitable (and also inhabited).

The international team was led by Alejandro Mascareño of the Canary Islands Institute of Astrophysics (IAC), and includes members from the University of La Laguna and the University of Geneva. Their research was also supported by the Spanish National Research Council (CSIS), the Institute of Space Studies of Catalonia (IEEC), and the National Institute For Astrophysics (INAF).

The study which details their findings was recently accepted for publication by the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, and appears online under the title “A super-Earth on the Inner Edge of the Habitable Zone of the Nearby M-dwarf GJ 625“. According to the study, the team used radial-velocity measurements of GJ 625 in order to determine the presence of a planet that has between two and three times the mass of Earth.

This discovery was part of the HArps-n red Dwarf Exoplanet Survey (HADES), which studies red dwarf stars to determine the presence of potentially habitable planets orbiting them. This survey relies on the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher for the Northern hemisphere (HARPS-N) instrument – which is part of the 3.6-meter Galileo National Telescope (TNG) at the IAC’s Roque de Los Muchachos Observatory on the island of La Palma.

Using this instrument, the team collected high-resolution spectroscopic data of the GJ 625 system over the course of three years. Specifically, they measured small variations in the stars radial velocity, which are attributed to the gravitational pull of a planet. From a total of 151 spectra obtained, they were able to determine that the planet (GJ 625 b) was likely terrestrial and had a minimum mass of 2.82 ± 0.51 Earth masses.

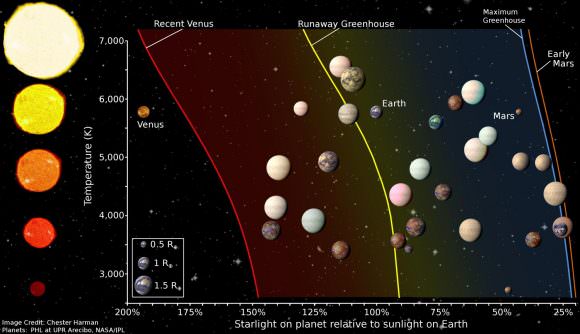

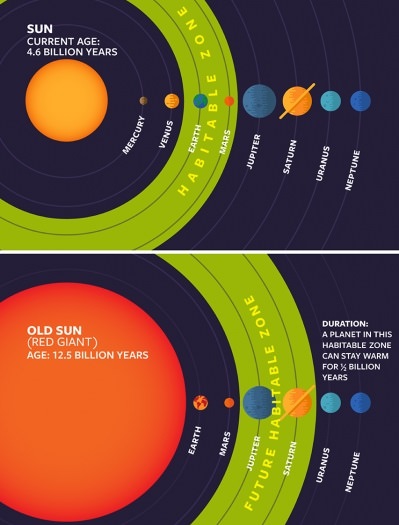

Moreover, they obtained distance estimates that placed it roughly 0.078 AU from its star, and an orbital period estimate of 14.628 ± 0.013 days. At this distance, the planet’s orbit places it just within GJ 625’s habitable zone. Of course, this does not mean conclusively that the planet has conditions conducive to life on its surface, but it is an encouraging indication.

As Alejandro Suárez Mascareño explained in an IAC press release:

“As GJ 625 is a relatively cool star the planet is situated at the edge of its habitability zone, in which liquid water can exist on its surface. In fact, depending on the cloud cover of its atmosphere and on its rotation, it could potentially be habitable”.

This is not the first time that the HADES project detected an exoplanet around a red dwarf star. In fact, back in 2016, a team of international researchers used this project to discover 2 super-Earths orbiting GJ 3998, a red dwarf located about 58 ± 2.28 light years from Earth. Beyond HADES, this discovery is yet another in a long line of rocky exoplanets that have been discovered in the habitable zone of a nearby red dwarf star.

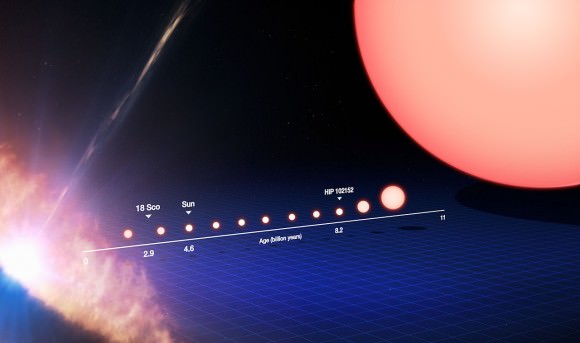

Such findings are very encouraging since red dwarfs are the most common type of star in the known Universe- accounting for an estimated 70% of stars in our galaxy alone. Combined with the fact that they can exist for up to 10 trillion years, red dwarf systems are considered a prime candidate in the search for habitable exoplanets.

But as with all other planets discovered around red dwarf stars, there are unresolved questions about how the star’s variability and stability could affect the planet. For starters, red dwarf stars are known to vary in brightness and periodically release gigantic flares. In addition, any planet close enough to be within the star’s habitable zone would likely be tidally-locked with it, meaning that one side would be exposed to a considerable amount of radiation.

As such, additional observations will need to be made of this exoplanet candidate using the time-tested transit method. According to Jonay Hernández – a professor from the University of La Laguna, a researcher with the IAC and one of the co-authors on the study – future studies using this method will not only be able to confirm the planet’s existence and characterize it, but also determine if there are any other planets in the system.

“In the future, new observing campaigns of photometric observations will be essential to try to detect the transit of this planet across its star, given its proximity to the Sun,” he said. “There is a possibility that there are more rocky planets around GJ 625 in orbits which are nearer to, or further away from the star, and within the habitability zone, which we will keep on combing”.

According to Rafael Rebolo – one of the study’s co-authors from the Univeristy of La Laguna, a research with the IAC, and a member of the CSIS – future surveys using the transit method will also allow astronomers to determine with a fair degree of certainty whether or not GJ 625 b has the all-important ingredient for habitability – i.e. an atmosphere:

“The detection of a transit will allow us to determine its radius and its density, and will allow us to characterize its atmosphere by the transmitted light observe using high resolution high stability spectrographs on the GTC or on telescopes of the next generation in the northern hemisphere, such as the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT)”.

But what is perhaps most exciting about this latest find is how it adds to the population of extra-solar planets within our cosmic neighborhood. Given their proximity, each of these planets represent a major opportunity for research. And as Dr. Mascareño told Universe Today via email:

“While we have already found more than 3600 extra-solar planets, the exoplanet population in our near neighborhood is still somewhat unknown. At 21 ly from the Sun, GJ 625 is one of the 100 nearest stars, and right now GJ 625 b is one of the 30 nearest exoplanets detected and the 6th nearest potentially habitable exoplanet.”

Once again, ongoing surveys of nearby star systems is providing plenty of potential targets in the search for life beyond our Solar System. And with both ground-based and space-based next-generation telescopes joining the search, we can expect to find many, many more candidates in the coming years. In the meantime, be sure to check out this animation of GJ 625 b and its parent star: