Our Milky Way is a pretty vast and highly-populated space. All told, its stars number between 100 and 400 billion, with some estimates saying that it may have as many as 1 trillion. But just where did all these stars come from? Well, as it turns out, in addition to forming many of its own and merging with other galaxies, the Milky Way may have stolen some of its stars from other galaxies.

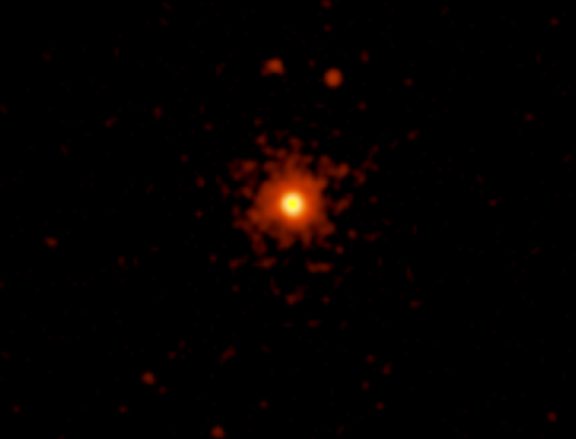

Such is the argument made by two astronomers from Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. According to their study, which has been accepted for publication in the The Astrophysical Journal, they claim that roughly half of the stars that orbit at the extreme outer edge of the Milky Way were actually stolen from the nearby Sagittarius dwarf galaxy.

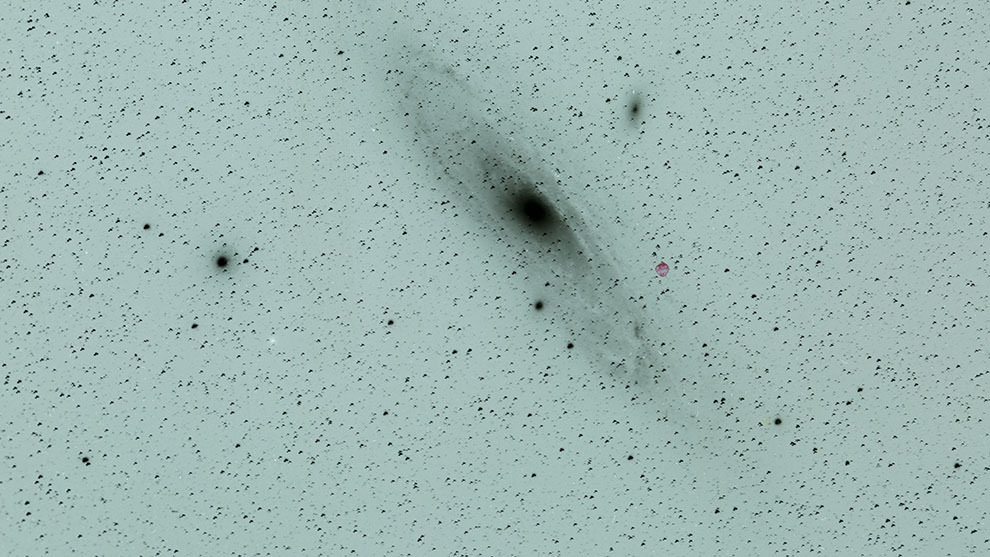

At one time, the Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy was thought to be the closest galaxy to our own (a position now held by the Canis Major dwarf galaxy). As one of several dozen dwarf galaxies that surround the Milky Way, it has orbited our galaxy several times in the past. With each passing orbit, it becomes subject to our galaxy’s strong gravity, which has the effect of pulling it apart.

The long-term effects of this can be seen by looking to the farthest stars in our galaxy, which consist of the eleven stars that are at a distance of about 300,000 light-years from Earth (well beyond the Milky Way’s spiral disk). According the study produced by Marion Dierickx, a graduate student at Harvard University’s Department of Astronomy, half of these stars were taken from the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy in the past.

Professor Avi Loeb, the Frank B. Baird, Jr. Professor of Science at Harvard and Marion Dierickx PhD advisor, co-authored the study – titled, “Predicted Extension of the Sagittarius Stream to the Milky Way Virial Radius“. As he told Universe Today via email:

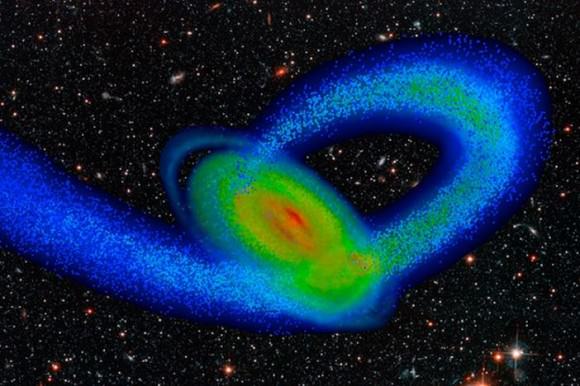

“We see evidence for streams of stars connected to the core of the galaxy, and indicating that this dwarf galaxy passed multiple times around the Milky Way center and was ripped apart by the tidal gravitational field of the Milky Way. We are all familiar with the tide in the ocean caused by the gravitational pull of the moon, but if the moon was a much more massive object – it would have pulled the oceans apart from the Earth and we would see a stream of vapor stretched away from the Earth.”

For the sake of their study, Dierickx and Loeb ran computer models to simulate the movements of the Sagittarius dwarf over the past 8 billion years. These simulations reproduced the streams of stars stretching away from the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy to the center of our galaxy. They also varied Sagittarius’ velocity and angle of approach to see if the resulting exchanges would match current observations.

“We attempted to match the distance and velocity data for the core of the Sagitarrius galaxy, and then compared the resulting prediction for the position and velocity of the streams of stars,” said Loeb. “The results were very encouraging for some particular set of initial conditions regarding the start of the Sagittarius galaxy journey when the universe was roughly half its present age.”

What they found was that over time, the Sagittarius dwarf lost about one-third of its stars and nine-tenths of its dark matter to the Milky Way. The end result of this was the creation of three distinct streams of stars that reach one million light-years from galactic center to the very edge of the Milky Way’s halo. Interestingly enough, one of these streams has been predicted by simulations conducted by projects like the Sloan Digital Survey.

The simulations also showed that five of Sagittarius’ stars would end becoming part of the Milky Way. What’s more, the positions and velocities of these stars coincided with five of the most distant stars in our galaxy. The other six do not appear to be from Sagittarius dwarf, and may be the result of gravitational interactions with another dwarf galaxy in the past.

“The dynamics of stars in the extended arms we predict (which is the largest Galactic structure on the sky ever predicted) can be used to measure the mass and structure of the Milky Way,” said Loeb. “The outer envelope of the Milky Way was never probed directly, because no other stream was known to extend that far.”

Given the way the simulations match up with current observations, Dierickx is confident that more Sagittarius dwarf interlopers are out there, just waiting to be found. For instance, future instruments – like the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST), which is expected to begin full-survey operations by 2022 – may be able to detect the two remaining streams of stars which were predicted by the survey.

Given the time scales and the distances involved, it is rather difficult to probe our galaxy (and by extension, the Universe) to see exactly how it evolved over time. Pairing observational data with computer models, however, has been proven to test our best theories of how things came to be. In the future, thanks to improved instruments and more detailed surveys, we just might know for certain!

And sure to check out this animation of the computer simulation, which shows the effects on the Milky Way’s gravity on the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy’s stars and dark matter.

Further Reading: CfA

![Comparison of best-fit size of the exoplanet GJ 1132 b with the Solar System planet Earth, as reported in the Open Exoplanet Catalogue[1] as of 2015-11-14. Open Exoplanet Catalogue (2015-11-14). Retrieved on 2015-11-14. Aldaron, a.k.a. Aldaro](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Exoplanet_Comparison_GJ_1132_b-e1471628608145-580x319.png)