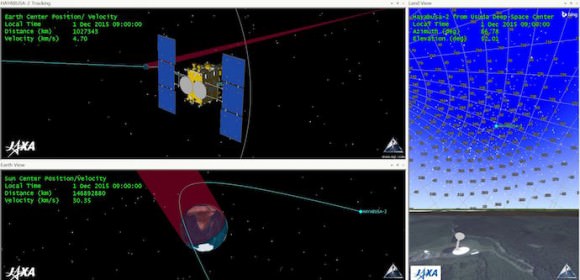

A space-faring friend pays our fair planet a visit this week on the morning of December 3rd, as the Japanese Space Agency’s Hayabusa 2 spacecraft passes the Earth.

The Flyby

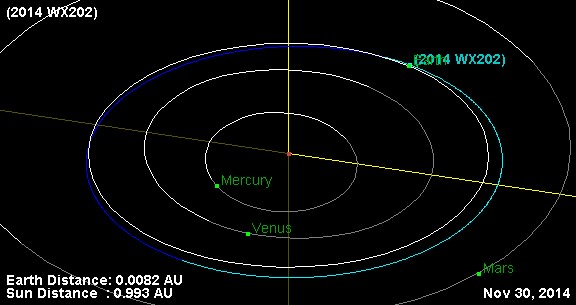

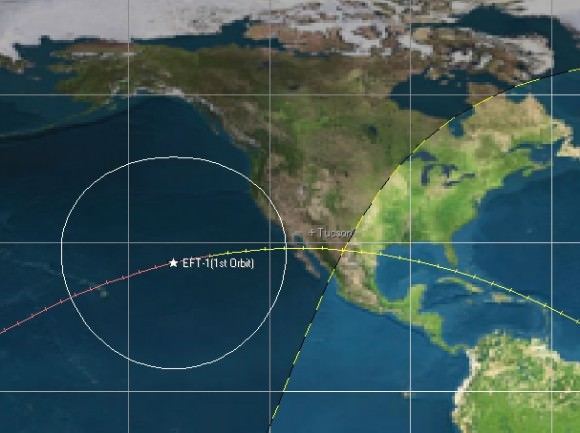

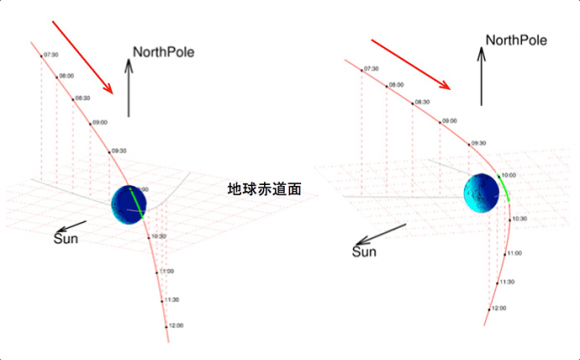

Rick Baldridge on the SeeSat-L message board notes that Hayabusa-2 will pass 9,520 kilometers from the Earth’s center or 3,142 kilometers/1,885 miles from the Earth’s surface at 10:08 UT/5:08 AM EST on Thursday, December 3rd, passing from north-to-south above latitude 18.7 north, longitude 189.8 east just southwest of the Hawaiian Islands.

Unfortunately, the sighting opportunities for Hayabusa-2 aren’t stellar: even at its closest, the 1.5 meter-sized spacecraft is about nine times more distant than the International Space Station and satellites in low Earth orbit. To compound the challenge, Hayabusa-2 passes into the Earth’s shadow from 9:58 UT to 10:19 UT.

Still, skilled observers with large telescopes and sophisticated tracking rigs based along the Pacific Rim of North America might just catch sight of Hayabusa-2 as it speeds by. The JPL Horizons ephemeris generator is a great resource to create a customized positional chart in right ascension and declination for spacecraft for your given location, including Hayabusa-2.

Hayabusa-2 won’t crack 20 degrees elevation for observers along the U.S. West Coast, putting it down in the atmospheric murk of additional air mass low to the horizon. This also tends to knock the brightness of objects down a magnitude or so… estimates place Hayabusa-2 at around magnitude +13 shortly before entering the Earth’s shadow. That’s pretty faint, but still, there are some dedicated observers with amazing rigs out there, and it’s quite possible someone could nab it. Hawaii-based observers should have the best shot at it, though again, it’ll be in the Earth’s shadow at its very closest…

Amateur radio satellite trackers are also on the hunt for the carrier-wave signal of the inbound Hayabusa-2 mission. You can also virtually fly along with the spacecraft until December 5th: (H/T @ImAstroNix):

Probably the best eye-candy images will come from the spacecraft itself: already, Hayabusa-2 has already snapped some great images of the Earth-Moon pair using its ONC-T optical navigation camera during its inbound leg.

Other notable missions used Earth flybys en route to their final destinations, including Cassini in 1999, and Juno in 2013. Cassini’s return caused a bit of a stir as it has a plutonium-powered RTG aboard, though Earth and its inhabitants were never in danger. A nuclear RTG actually reentered during the return of Apollo 13, with no release of radioactive material. Meant for the ALSEP science package on the surface of the Moon, it was deposited on the reentry of the Lunar Module over the Marinas Trench in the South Pacific. And no, Hayabusa-2 carries no radioactive material, and in any event, it’s missing the Earth by about a quarter of its girth.

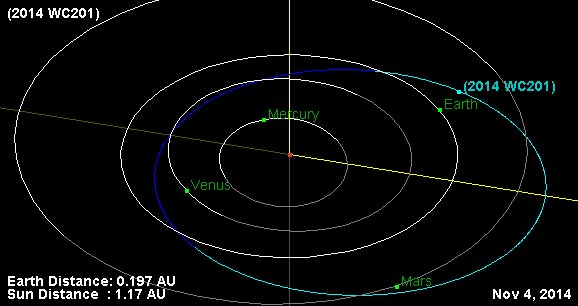

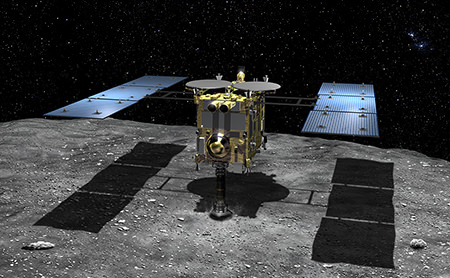

The successor to the Hayabusa (‘Peregrine Falcon’ in Japanese) mission which carried out a historic asteroid sample return from 25143 Itokawa in 2010, Hayabusa-2 launched atop an H-IIA rocket from Tanegashima, Japan exactly a year ago tomorrow on a six year mission to asteroid 162173 Ryugu. This week’s Earth flyby will boost the spacecraft an additional 1.6 kilometers per second to an outbound velocity towards its target of 31.9 kilometers per second post-flyby.

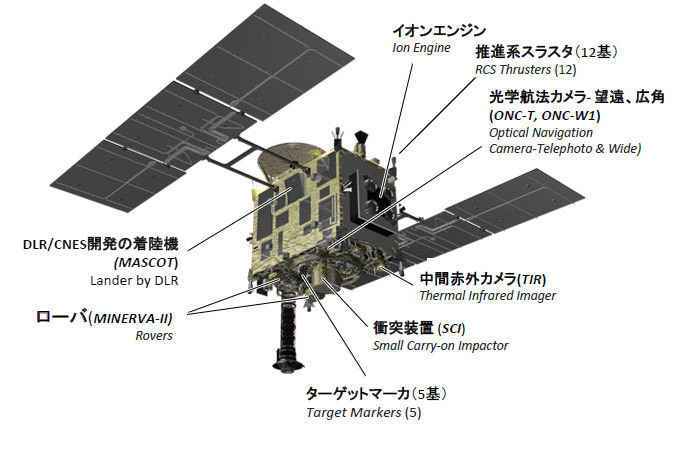

Like its predecessor, Hayabusa-2 is a sample return mission. Unlike the original Hayabusa, however, Hayabusa-2 is more ambitious, also carrying the MASCOT (Mobile Asteroid Surface Scout) lander and an explosive seven kilogram impactor. Hayabusa-2 will deploy a secondary camera in orbit to watch the detonation and will briefly touch down at the impact site to collect material.

If all goes as planned, Hayabusa-2 will return to Earth in late 2020.

NASA has its own future asteroid sample return mission planned, named OSIRIS-REx. This mission will launch in September of next year to rendezvous with asteroid 101955 Bennu in September 2019 and return to Earth in September 2023.

We’re entering the golden age of asteroid exploration, for sure. And this all comes about as the U.S. authorized asteroid mining just last week (or at least, as stated, ‘asteroid utilization’) under the controversial U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act. But the original Hayabusa mission brought back mere micro-meter-sized dust grains, highlighting just how difficult asteroid mining is using present technology…

Perhaps, for now, its more cost effective to simply wait for the asteroids to come to us as meteorites and just scoop ’em up. We’ll be keeping an eye out over the next few days for images of Hayabusa-2 as it speeds by, and more postcards of the Earth-Moon system from the spacecraft as it heads towards its 2018 rendezvous with destiny.