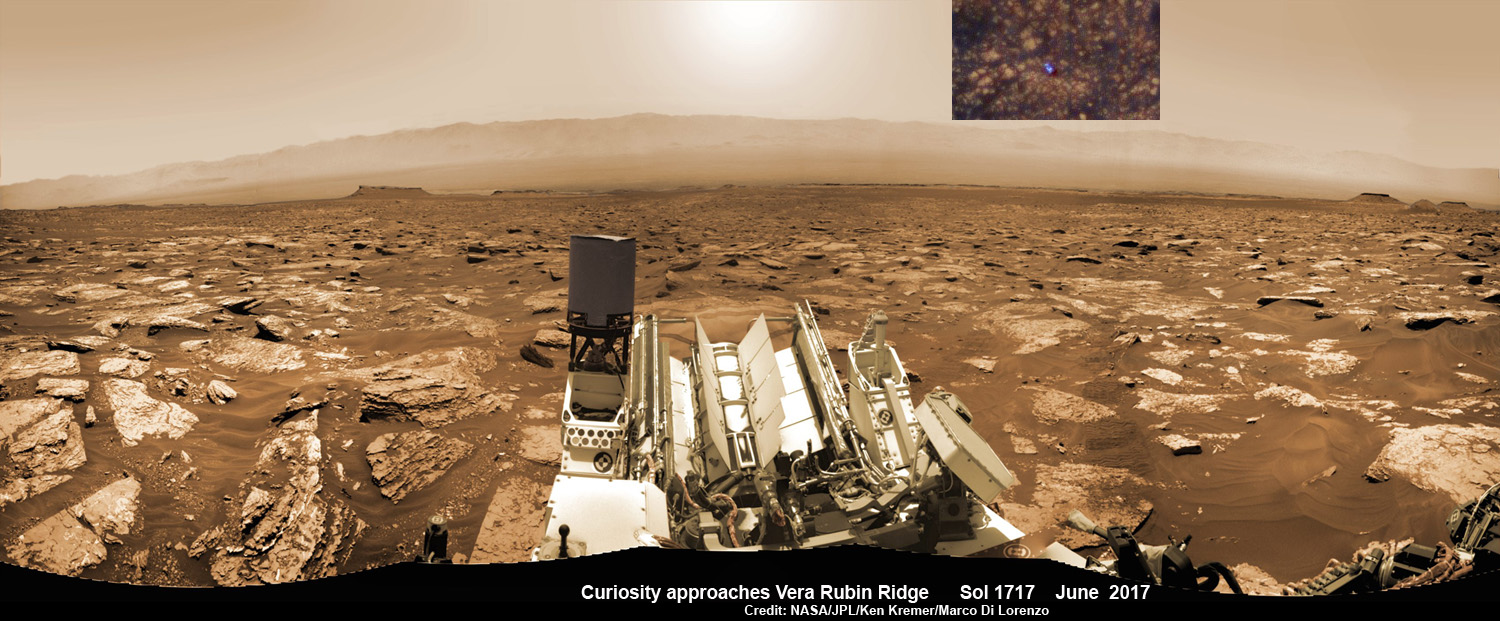

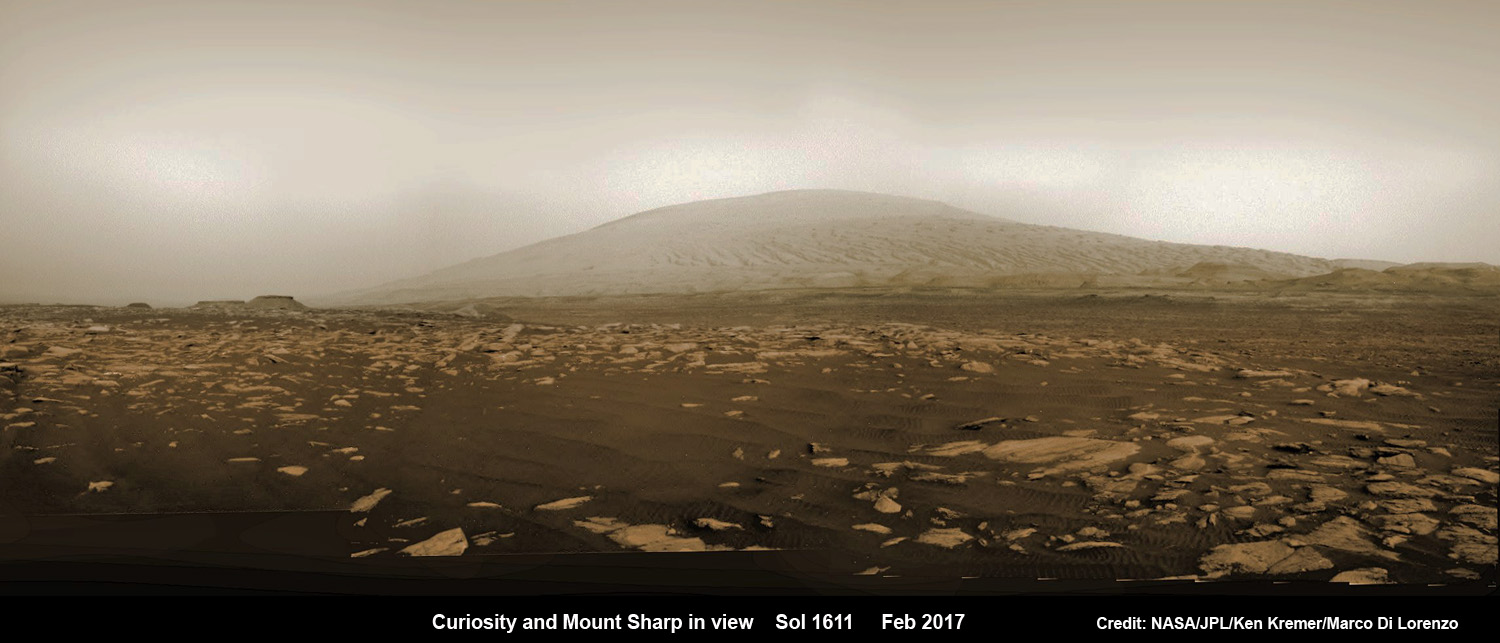

5 years after a heart throbbing Martian touchdown, Curiosity is climbing Vera Rubin Ridge in search of “aqueous minerals” and “clays” for clues to possible past life while capturing “truly breathtaking” vistas of humongous Mount Sharp – her primary destination – and the stark eroded rim of the Gale Crater landing zone from ever higher elevations, NASA scientists tell Universe Today in a new mission update.

“Curiosity is doing well, over five years into the mission,” Michael Meyer, NASA Lead Scientist, Mars Exploration Program, NASA Headquarters told Universe Today in an interview.

“A key finding is the discovery of an extended period of habitability on ancient Mars.”

The car-sized rover soft landed on Mars inside Gale Crater on August 6, 2012 using the ingenious and never before tried “sky crane” system.

A rare glimpse of Curiosity’s arm and turret mounted skyward pointing drill is illustrated with our lead mosaic from Sol 1833 of the robot’s life on Mars – showing a panoramic view around the alien terrain from her current location in October 2017 while actively at work analyzing soil samples.

“Your mosaic is absolutely gorgeous!’ Jim Green, NASA Director Planetary Science Division, NASA Headquarters, Washington D.C., told Universe Today

“We are at such a height on Mt Sharp to see the rim of Gale Crater and the top of the mountain. Truly breathtaking.”

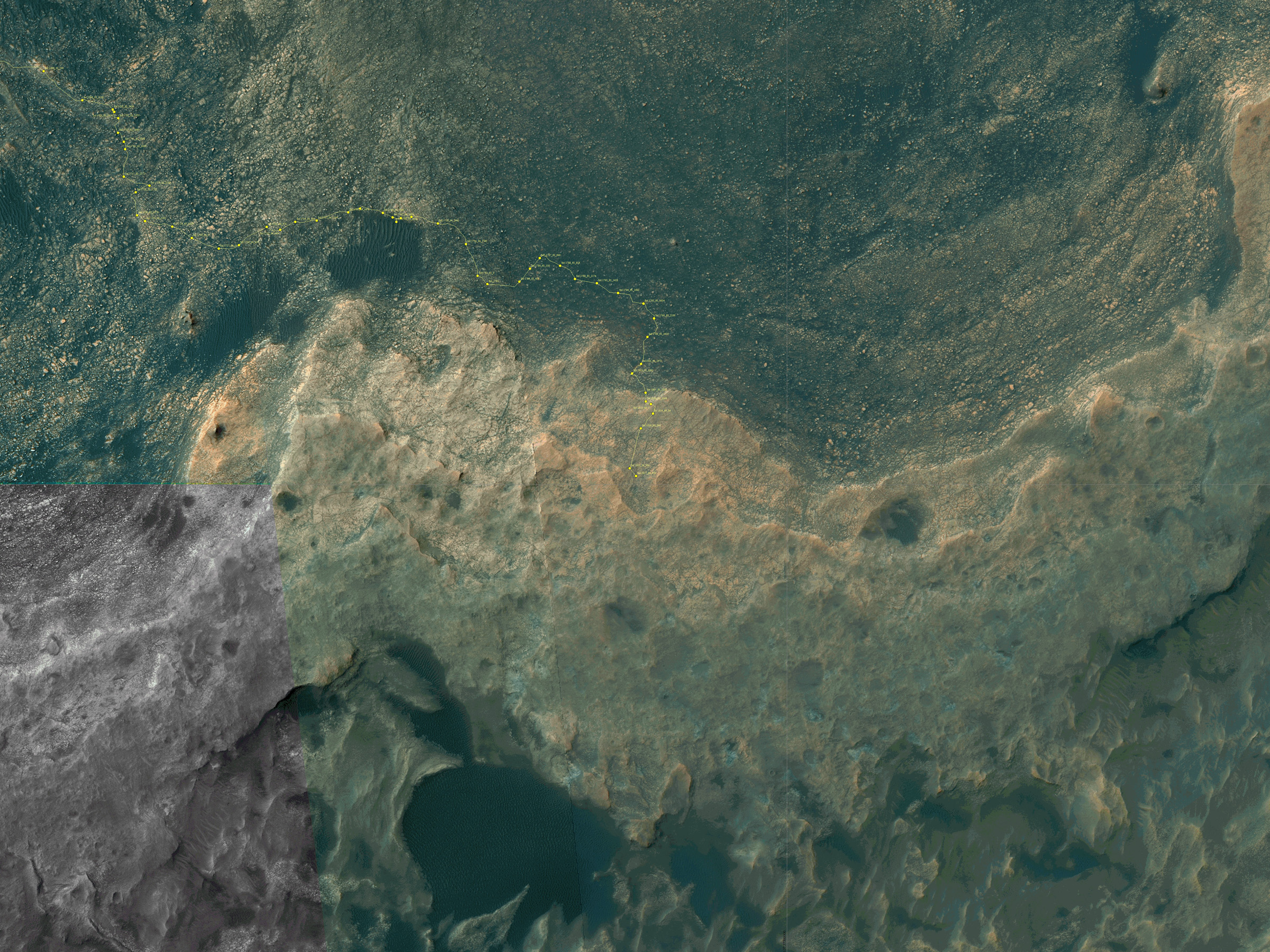

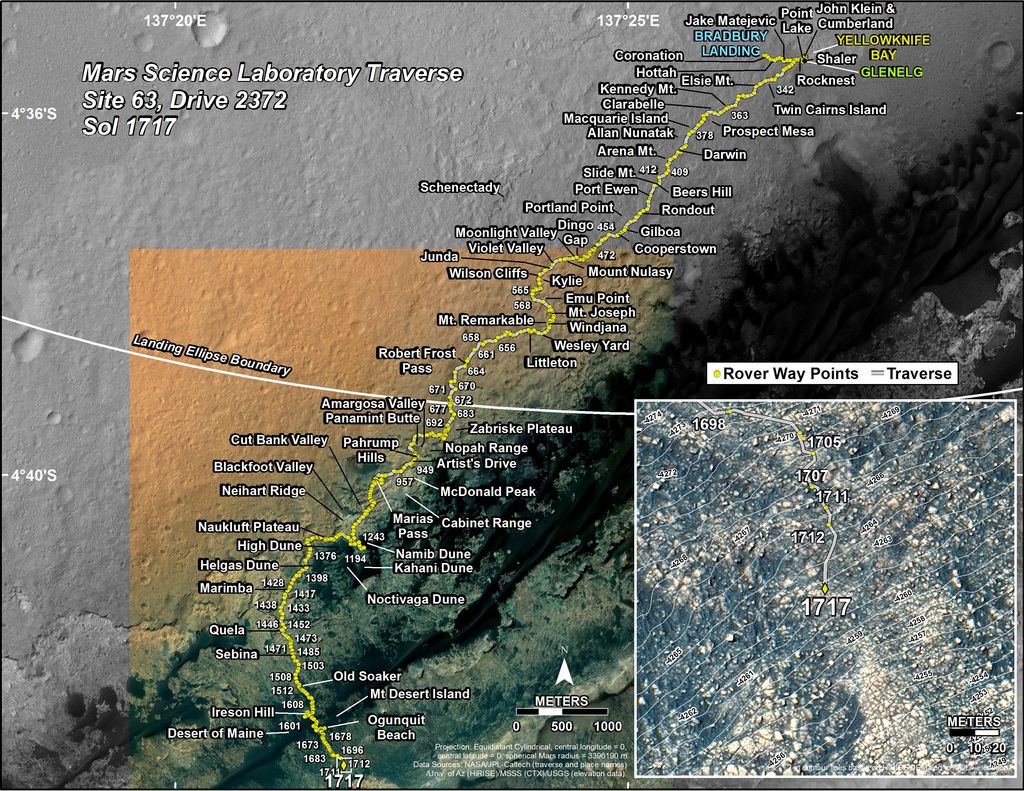

The rover has ascended more than 300 meters in elevation over the past 5 years of exploration and discovery from the crater floor to the mountain ridge. She is driving to the top of Vera Rubin Ridge at this moment and always on the lookout for research worthy targets of opportunity.

Additionally, the Sol 1833 Vera Rubin Ridge mosaic, stitched by the imaging team of Ken Kremer and Marco Di Lorenzo, shows portions of the trek ahead to the priceless scientific bounty of aqueous mineral signatures detected by spectrometers years earlier from orbit by NASA’s fleet of Red Planet orbiters.

“Curiosity is on Vera Rubin Ridge (aka Hematite Ridge) – it is the first aqueous mineral signature that we have seen from space, a driver for selecting Gale Crater,” NASA HQ Mars Lead Scientist Meyer elaborated.

“And now we have access to it.”

The Sol 1833 photomosaic illustrates Curiosity maneuvering her 7 foot long (2 meter) robotic arm during a period when she was processing and delivering a sample of the “Ogunquit Beach” for drop off to the inlet of the CheMin instrument earlier in October. The “Ogunquit Beach” sample is dune material that was collected at Bagnold Dune II this past spring.

The sample drop is significant because the drill has not been operational for some time.

“Ogunquit Beach” sediment materials were successfully delivered to the CheMin and SAM instruments over the following sols and multiple analyses are in progress.

To date three CheMin integrations of “Ogunquit Beach” have been completed. Each one brings the mineralogy into sharper focus.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS

What’s the status of the rover health at 5 years, the wheels and the drill?

“All the instruments are doing great and the wheels are holding up,” Meyer explained.

“When 3 grousers break, 60% life has been used – this has not happened yet and they are being periodically monitored. The one exception is the drill feed (see detailed update below).”

NASA’s 1 ton Curiosity Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) rover is now closer than ever to the mineral signatures that were the key reason why Mount Sharp was chosen as the robots landing site years ago by the scientists leading the unprecedented mission.

Along the way from the ‘Bradbury Landing’ zone to Mount Sharp, six wheeled Curiosity has often been climbing. To date she has gained over 313 meters (1027 feet) in elevation – from minus 4490 meters to minus 4177 meters today, Oct. 19, 2017, said Meyer.

The low point was inside Yellowknife Bay at approx. minus 4521 meters.

VRR alone stands about 20 stories tall and gains Curiosity approx. 65 meters (213 feet) of elevation to the top of the ridge. Overall the VRR traverse is estimated by NASA to take drives totaling more than a third of a mile (570 m).

“Vera Rubin Ridge” or VRR is also called “Hematite Ridge.” It’s a narrow and winding ridge located on the northwestern flank of Mount Sharp. It was informally named earlier this year in honor of pioneering astrophysicist Vera Rubin.

The intrepid robot reached the base of the ridge in early September.

The ridge possesses steep cliffs exposing stratifications of large vertical sedimentary rock layers and fracture filling mineral deposits, including the iron-oxide mineral hematite, with extensive bright veins.

VRR resists erosion better than the less-steep portions of the mountain below and above it, say mission scientists.

What’s ahead for Curiosity in the coming weeks and months exploring VRR before moving onward and upwards to higher elevation?

“Over the next several months, Curiosity will explore Vera Rubin Ridge,” Meyer replied.

“This will be a big opportunity to ground-truth orbital observations. Of interest, so far, the hematite of VRR does not look that different from what we have been seeing all along the Murray formation. So, big question is why?”

“The view from VRR also provides better access to what’s ahead in exploring the next aqueous mineral feature – the clay, or phyllosilicates, which can be indicators of specific environments, putting constraints on variables such as pH and temperature,” Meyer explained.

The clay minerals or phyllosilicates form in more neutral water, and are thus extremely scientifically interesting since pH neutral water is more conducive to the origin and evolution of Martian microbial life forms, if they ever existed.

How far away are the clays ahead and when might Curiosity reach them?

“As the crow flies, the clays are about 0.5 km,” Meyer replied. “However, the actual odometer distance and whether the clays are where we think they are – area vs. a particular location – can add a fair degree of variability.”

The clay rich area is located beyond the ridge.

Over the past few months Curiosity make rapid progress towards the hematite-bearing location of Vera Rubin Ridge after conducting in-depth exploration of the Bagnold Dunes earlier this year.

“Vera Rubin Ridge is a high-standing unit that runs parallel to and along the eastern side of the Bagnold Dunes,” said Mark Salvatore, an MSL Participating Scientist and a faculty member at Northern Arizona University, in a mission update.

“From orbit, Vera Rubin Ridge has been shown to exhibit signatures of hematite, an oxidized iron phase whose presence can help us to better understand the environmental conditions present when this mineral assemblage formed.”

Curiosity is using the science instruments on the mast, deck and robotic arm turret to gather detailed research measurements with the cameras and spectrometers. The pair of miniaturized chemistry lab instruments inside the belly – CheMin and SAM – are used to analyze the chemical and elemental composition of pulverized rock and soil gathered by drilling and scooping selected targets during the traverse.

A key instrument is the drill which has not been operational. I asked Meyer for a drill update.

“The drill feed developed problems retracting (two stabilizer prongs on either side of the drill retract, controlling the rate of drill penetration),” Meyer replied.

“Because the root cause has not been found (think FOD) and the concern about the situation getting worse, the drill feed has been retracted and the engineers are working on drilling without the stabilizing prongs.”

“Note, a consequence is that you can still drill and collect sample but a) there is added concern about getting the drill stuck and b) a new method of delivering sample needs to be developed and tested (the drill feed normally needs to be moved to move the sample into the chimera). One option that looks viable is reversing the drill – it does work and they are working on the scripts and how to control sample size.”

Ascending and diligently exploring the sedimentary lower layers of Mount Sharp, which towers 3.4 miles (5.5 kilometers) into the Martian sky, is the primary destination and goal of the rover’s long term scientific expedition on the Red Planet.

“Lower Mount Sharp was chosen as a destination for the Curiosity mission because the layers of the mountain offer exposures of rocks that record environmental conditions from different times in the early history of the Red Planet. Curiosity has found evidence for ancient wet environments that offered conditions favorable for microbial life, if Mars has ever hosted life,” says NASA.

Stay tuned. In part 2 we’ll discuss the key findings from Curiosity’s first 5 years exploring the Red Planet.

As of today, Sol 1850, Oct. 19, 2017, Curiosity has driven over 10.89 miles (17.53 kilometers) since its August 2012 landing inside Gale Crater from the landing site to the ridge, and taken over 445,000 amazing images.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.