Eta Carinae, a double star system located 7,500 light years away in the constellation Carina, has a combined luminosity of more than 5 million Suns – making it one of the brightest stars in the Milky Way galaxy. But 170 years ago, between 1837 and 1858, this star erupted in what appeared to be a massive supernova, temporarily making it the second brightest star in the sky.

Strangely, this blast was not enough to obliterate the star system, which left astronomers wondering what could account for the massive eruption. Thanks to new data, which was the result of some “forensic astronomy” (where leftover light from the explosion was examined after it reflected off of interstellar dust) a team of astronomers now think they have an explanation for what happened.

The studies which describe their findings – titled “Exceptionally fast ejecta seen in light echoes of Eta Carinae’s Great Eruption” and “Light echoes from the plateau in Eta Carinae’s Great Eruption reveal a two-stage shock-powered event” – recently appeared in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Both studies were led by Nathan Smith of the University of Arizona’s Steward Observatory, and included members from the

In their first study, the team indicates how they studied the “light echoes” produced by the explosion, which were reflected off of interstellar dust and are just now visible from Earth. From this, they observed that the eruption resulted in material expanding at speeds that were up to 20 times faster than with any previously-observed supernova.

In the second study, the team studied the evolution of the echo’s light curve, which revealed that it experienced spikes before 1845, then plateaued until 1858 before steadily declining over the next decade. Basically, the observed velocities and light curve were consistent with the blast wave of a supernova explosion rather than the relatively slow and gentle winds expected from massive stars before they die.

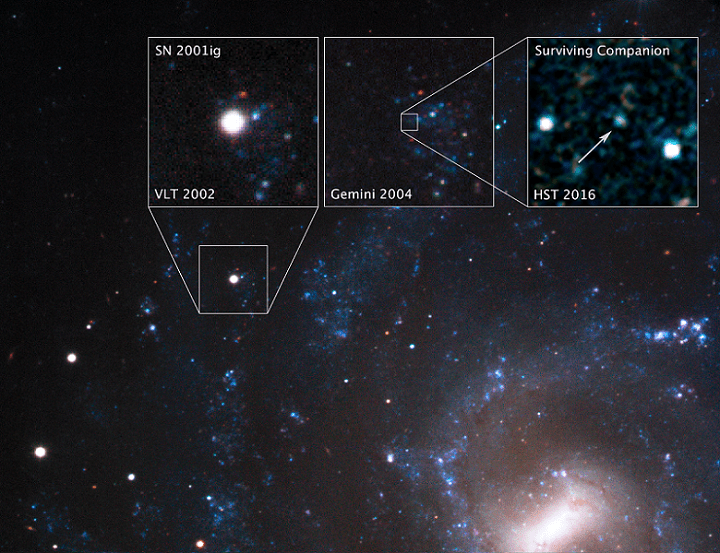

The light echoes were first detected in images obtained in 2003 by telescopes at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile. For the sake of their study, the team consulted spectroscopic data from the Magellan telescopes at the Las Campanas Observatory and the Gemini South Observatory, both located in Chile. This allowed the team to measure the light and determine the ejecta’s expansion speeds – more than 32 million km/h (20 million mph).

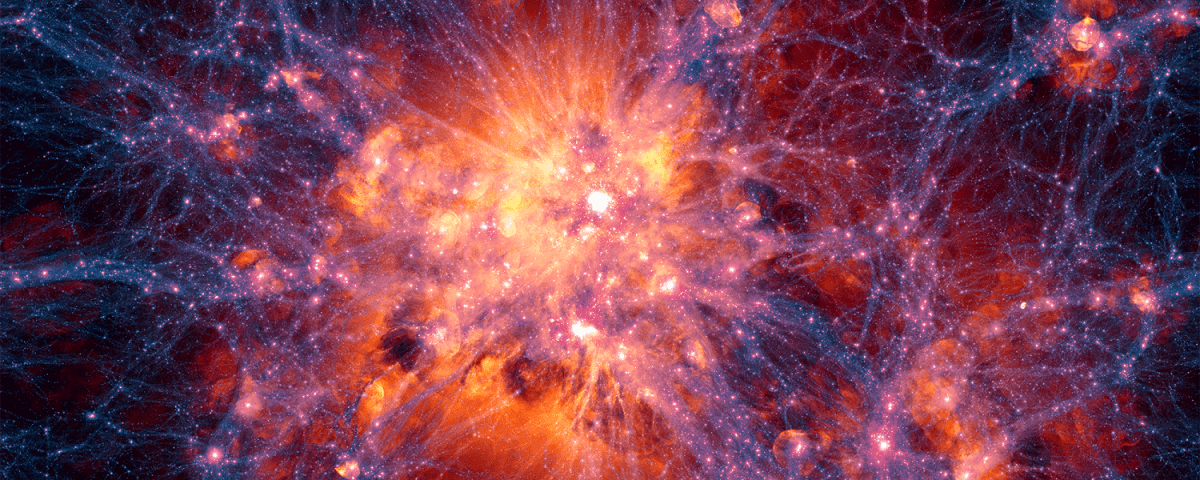

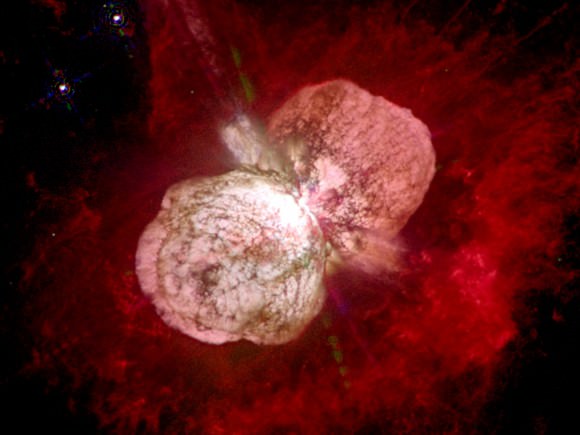

Based on this data, the team hypothesized that the eruption may have been triggered by a prolonged battle between three stars, which destroyed one star and left the other two in a binary system. This battle may have culminated with a violent explosion when Eta Carinae devoured one of its two companions, sending more than 10 Solar masses into space. This ejected mass created the gigantic bipolar nebula (aka. “the Homunculus Nebula”) which is seen today.

As Smith explained in a recent HubbleSite press release:

“We see these really high velocities in a star that seems to have had a powerful explosion, but somehow the star survived. The easiest way to do this is with a shock wave that exits the star and accelerates material to very high speeds.”

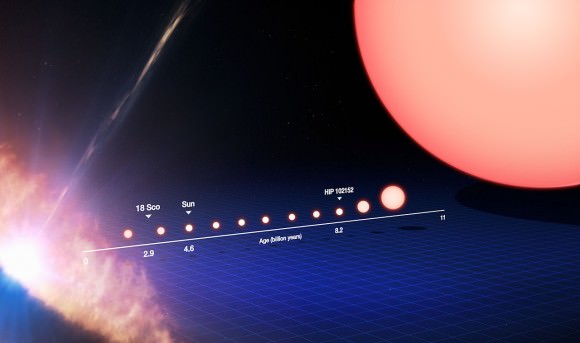

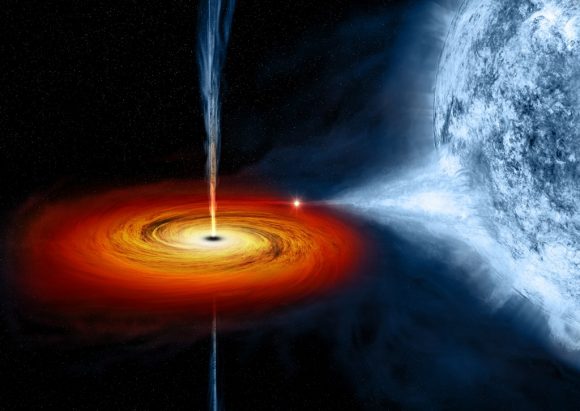

In this scenario, Eta Carinae started out as a trinary system, with two massive stars orbiting close to each other and the third orbiting further away. When the most massive of the binary neared the end of its life, it began to expand and then transfer much of its material onto its slightly smaller companion. This caused the smaller star to accumulate just enough energy to cause it to eject its outer layers, but not enough to completely annihilate it.

The companion star would have then grown to become about 100 times the mass of our Sun and extremely bright. The other star, now weighing only 30 Solar masses, would have been stripped of its hydrogen layers, exposing its hot helium core – which represent an advanced stage of evolution in the lives of massive stars. As Armin Rest – a researcher from the explained:

“From stellar evolution, there’s a pretty firm understanding that more massive stars live their lives more quickly and less massive stars have longer lifetimes. So the hot companion star seems to be further along in its evolution, even though it is now a much less massive star than the one it is orbiting. That doesn’t make sense without a transfer of mass.”

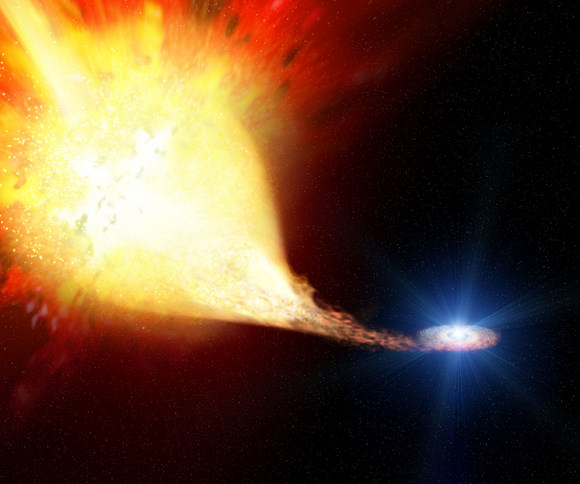

This transfer of mass would have altered the gravitational balance of the system, causing the helium-core star to move farther away from its now-massive companion and eventually travel so far that it would interact with the outermost third star. This would cause the third star to move towards the massive star and eventually merge with it, producing an outflow of material.

Initially, the merger caused ejecta that expanded relatively slowly, but as the two stars finally joined together, they produced an explosive event that blasted material off 100 times faster. This material caught up to the slow ejecta, pushing it forward and heating the material until it glowed. This glowing material was the main light source that was viewed by astronomers 170 years ago.

In the end, the smaller helium-core star settled into an elliptical orbit around around its massive counterpart, passing through the star’s outer layers every 5.5 years and generating X-ray shock waves. According to Smith, while this explanation cannot account for everything observed in Eta Carinae, it does explain both the brightening and the fact that the star remains:

“The reason why we suggest that members of a crazy triple system interact with each other is because this is the best explanation for how the present-day companion quickly lost its outer layers before its more massive sibling.”

These studies have provided new clues as to the mystery of how Eta Carinae appeared to explode in a massive supernova, but left behind a massive star and nebula. In addition, a better understanding of the physics behind the Eta Carinae explosion could help astronomers to learn more about the complicated interactions that govern binary and multiple star systems – which are critical to our understanding of the evolution and death of massive stars.

Further Reading: HubbleSite, MNRAS, MNRAS (2)