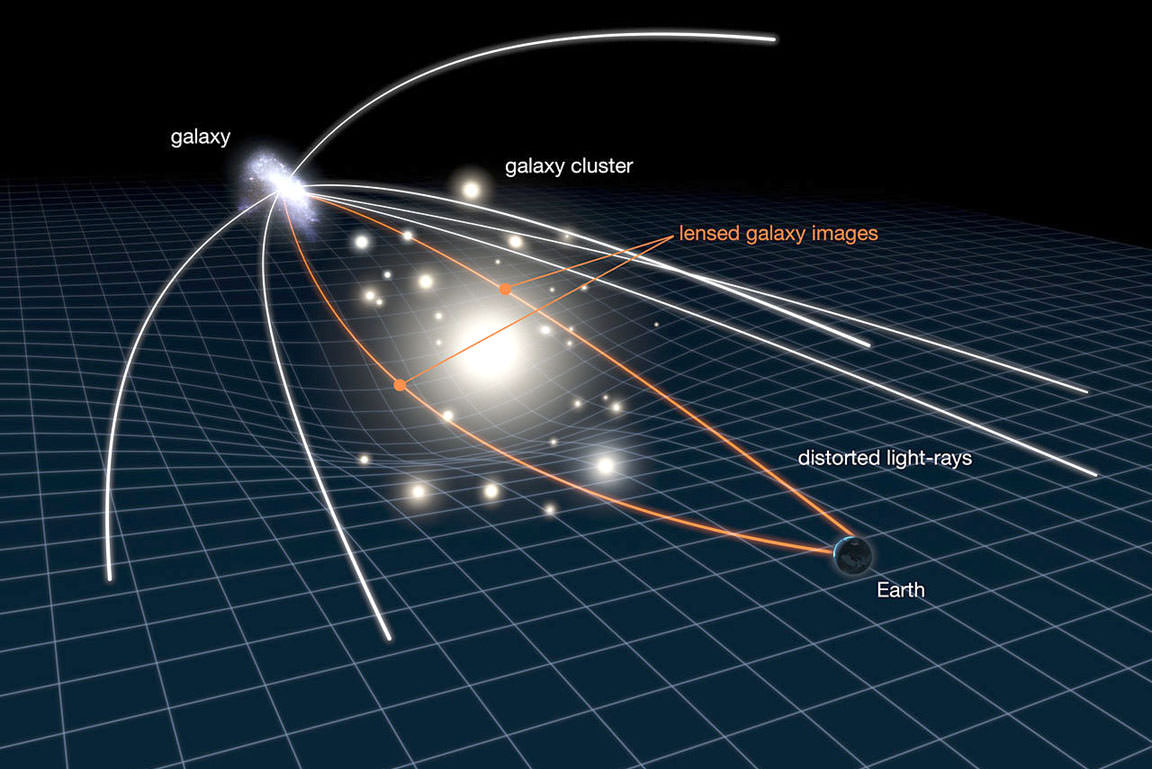

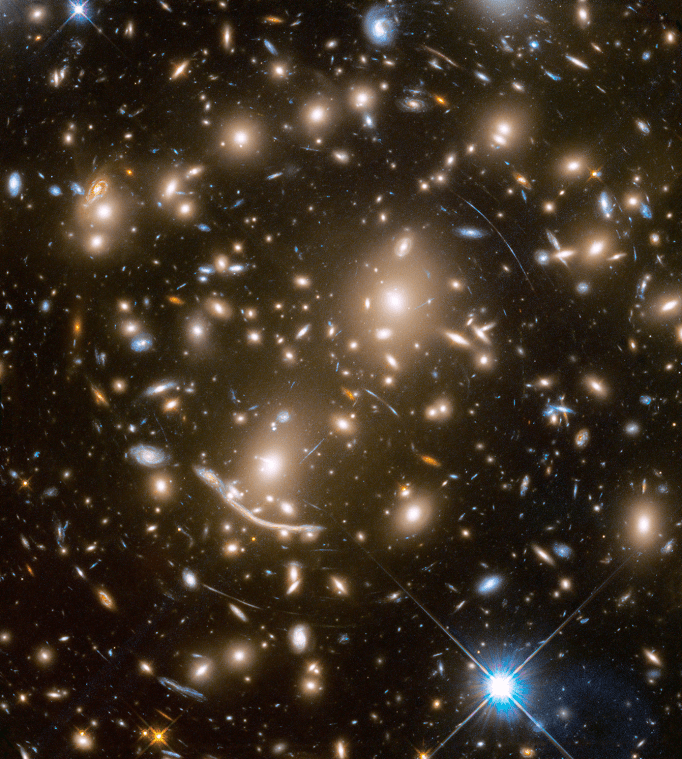

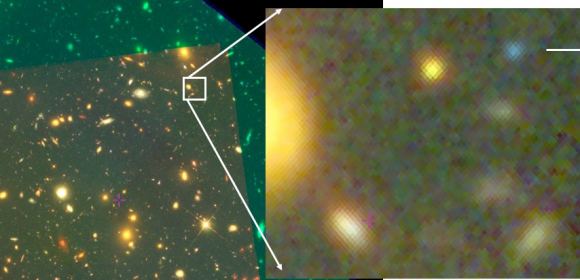

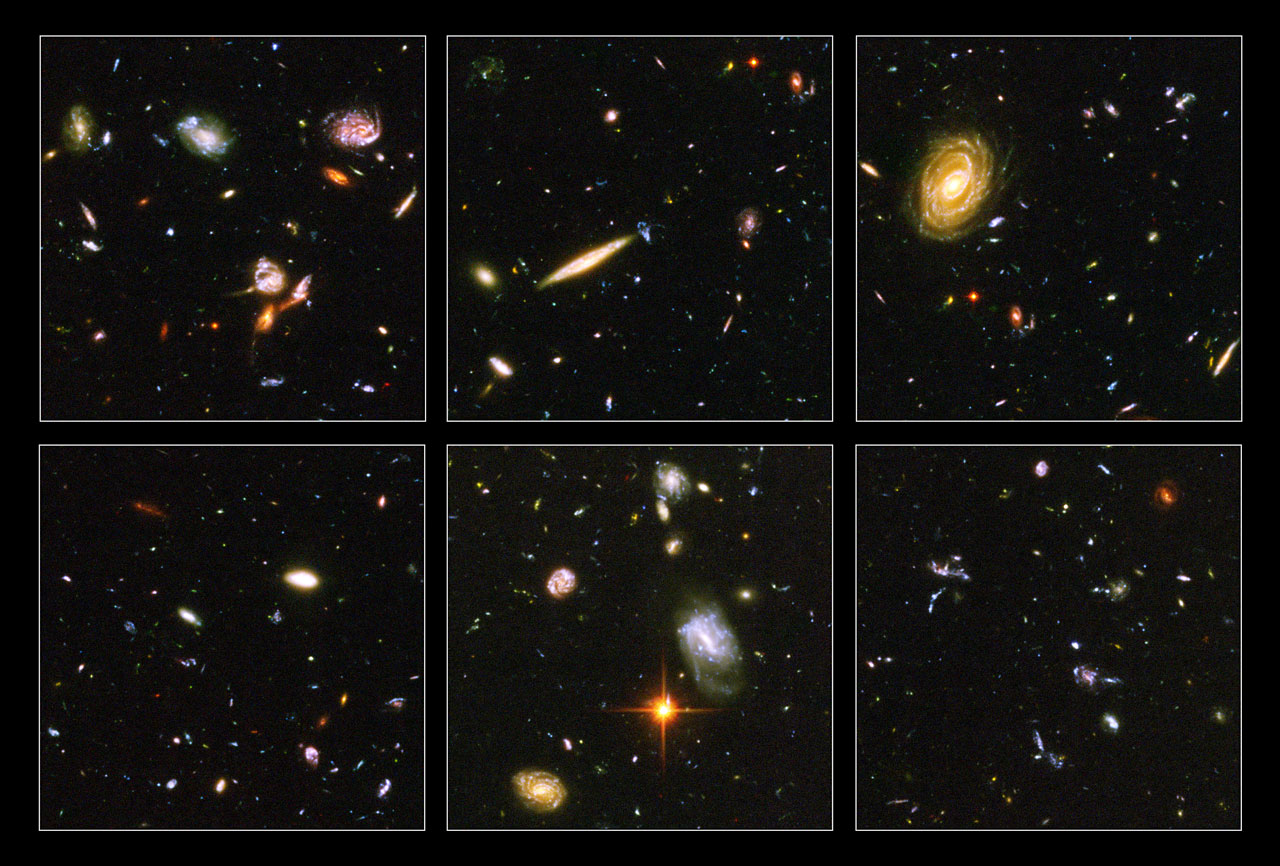

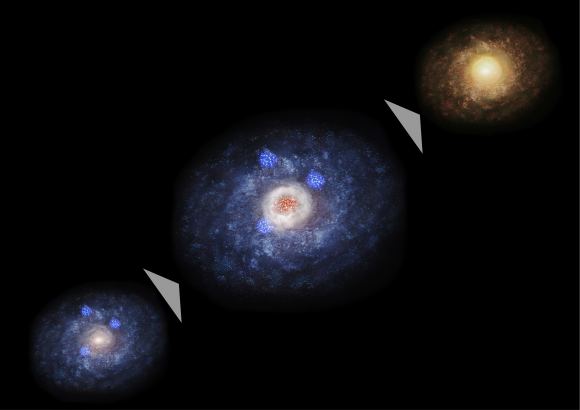

When it comes to studying some of the most distant and oldest galaxies in the Universe, a number of challenges present themselves. In addition to being billions of light years away, these galaxies are often too faint to see clearly. Luckily, astronomers have come to rely on a technique known as Gravitational Lensing, where the gravitational force of a large object (like a galactic cluster) is used to enhance the light of these fainter galaxies.

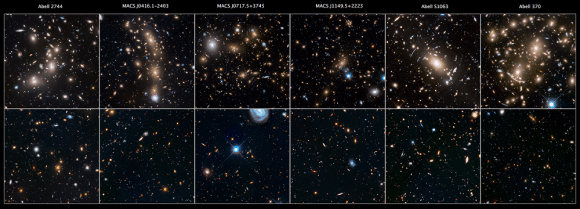

Using this technique, an international team of astronomers recently discovered a distant and quiet galaxy that would have otherwise gone unnoticed. Led by researchers from the University of Hawaii at Manoa, the team used the Hubble Space Telescope to conduct the most extreme case of gravitational lensing to date, which allowed them to observe the faint galaxy known as eMACSJ1341-QG-1.

The study that describes their findings recently appeared in The Astrophysical Journal Letters under the title “Thirty-fold: Extreme Gravitational Lensing of a Quiescent Galaxy at z = 1.6″. Led by Harald Ebeling, an astronomer from the University of Hawaii at Manoa, the team included members from the Niels Bohr Institute, the Centre Nationale de Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), the Space Telescope Science Institute, and the European Southern Observatory (ESO).

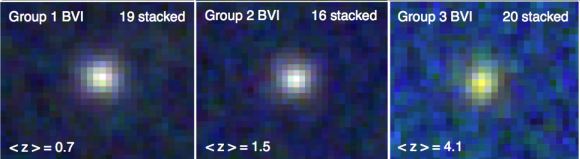

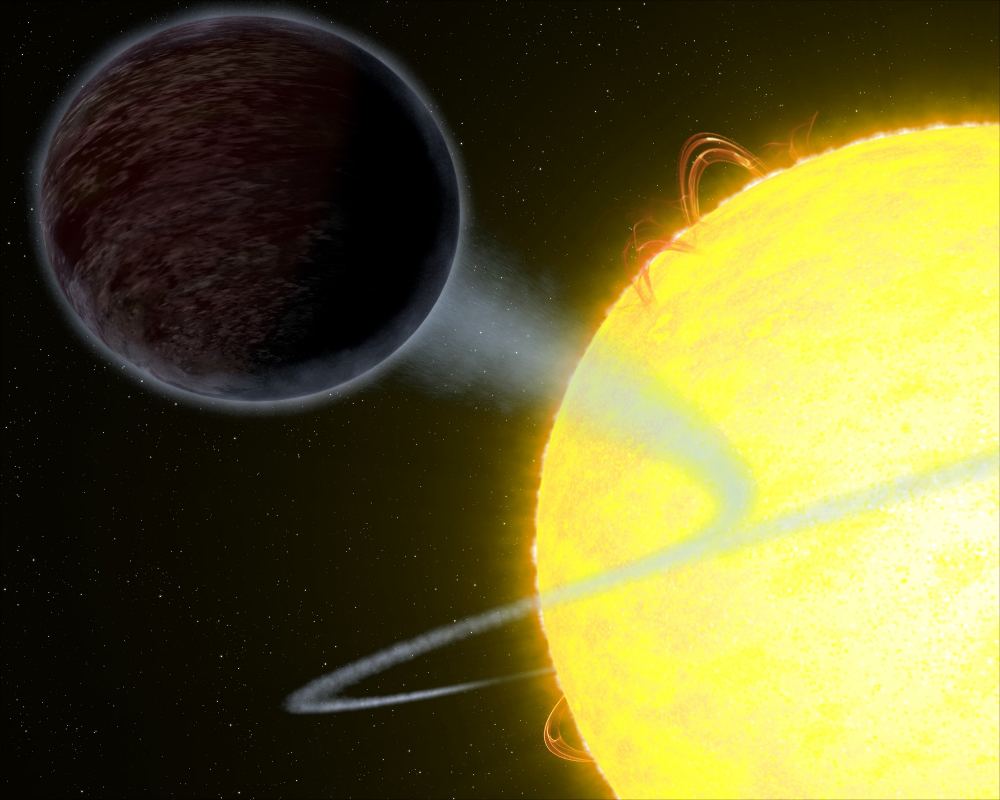

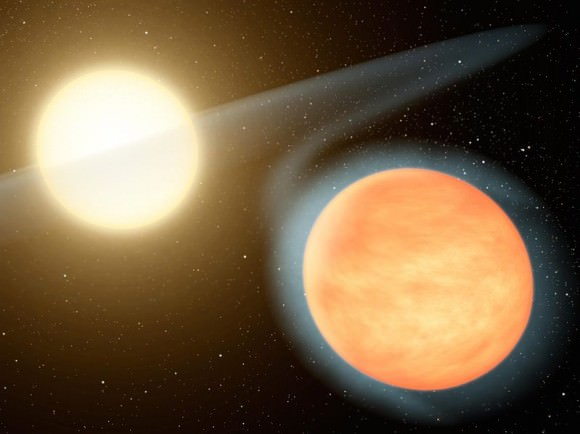

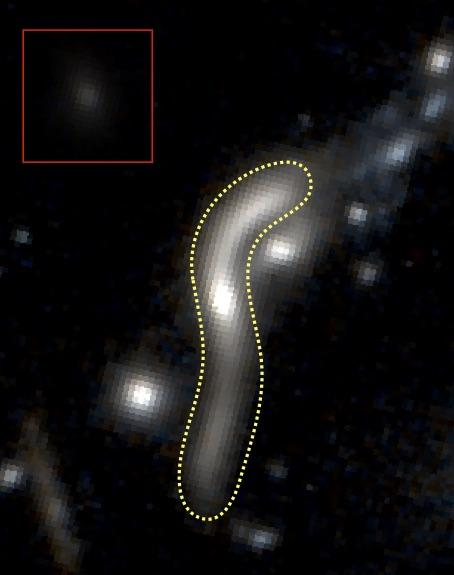

For the sake of their study, the team relied on the massive galaxy cluster known as eMACSJ1341.9-2441 to magnify the light coming from eMACSJ1341-QG-1, a distant and fainter galaxy. In astronomical terms, this galaxy is an example of a “quiescent galaxy”, which are basically older galaxies that have largely depleted their supplies of dust and gas and therefore do not form new stars.

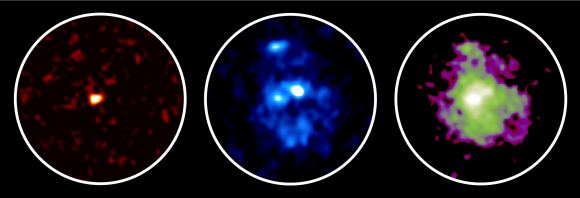

The team began by taking images of the faint galaxy with the Hubble and then conducting follow-up spectroscopic observations using the ESO/X-Shooter spectrograph – which is part of the Very Large Telescope (VLT) at the Paranal Observatory in Chile. Based on their estimates, the team determined that they were able to amplify the background galaxy by a factor of 30 for the primary image, and a factor of six for the two remaining images.

This makes eMACSJ1341-QG-1 the most strongly amplified quiescent galaxy discovered to date, and by a rather large margin! As Johan Richard – an assistant astronomer at the University of Lyon who performed the lensing calculations, and a co-author on the study – indicated in a University of Hawaii News release:

“The very high magnification of this image provides us with a rare opportunity to investigate the stellar populations of this distant object and, ultimately, to reconstruct its undistorted shape and properties.”

Although other extreme magnifications have been conducted before, this discovery has set a new record for the magnification of a rare quiescent background galaxy. These older galaxies are not only very difficult to detect because of their lower luminosity; the study of them can reveal some very interesting things about the formation and evolution of galaxies in our Universe.

As Ebeling, an astronomer with the UH’s Institute of Astronomy and the lead author on the study, explained:

“We specialize in finding extremely massive clusters that act as natural telescopes and have already discovered many exciting cases of gravitational lensing. This discovery stands out, though, as the huge magnification provided by eMACSJ1341 allows us to study in detail a very rare type of galaxy.”

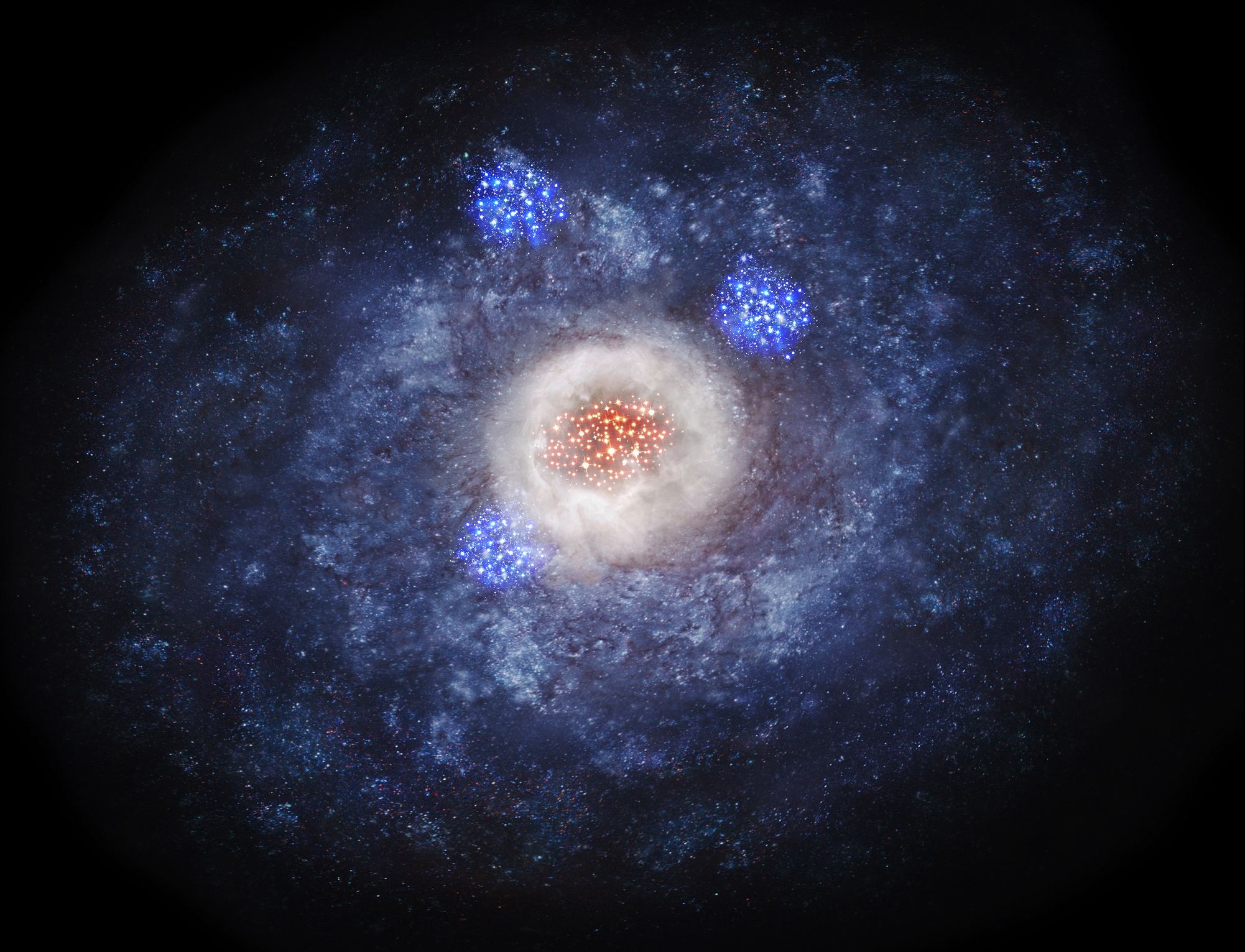

Quiescent galaxies are common in the local Universe, representing the end-point of galactic evolution. As such, this record-breaking find could provide some unique opportunities for studying these older galaxies and determining why star-formation ended in them. As Mikkel Stockmann, a team member from the University of Copenhagen and an expert in galaxy evolution, explained:

“[A]s we look at more distant galaxies, we are also looking back in time, so we are seeing objects that are younger and should not yet have used up their gas supply. Understanding why this galaxy has already stopped forming stars may give us critical clues about the processes that govern how galaxies evolve.”

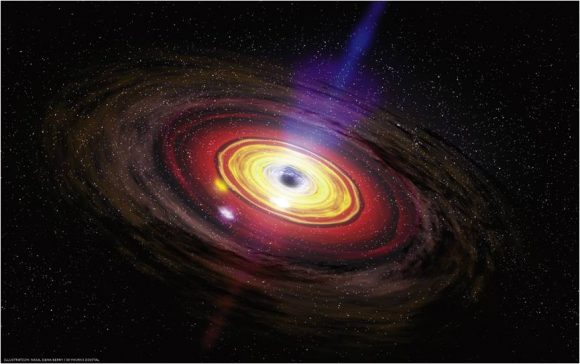

In a similar vein, recent studies have been conducted that suggest that the presence of a Supermassive Black Hole (SMBH) could be what is responsible for galaxies becoming quiescent. As the powerful jets these black holes create begin to drain the core of galaxies of their dust and gas, potential stars find themselves starved of the material they would need to undergo gravitational collapse.

In the meantime, follow-up observations of eMACSJ1341-QG1 are being conducted using telescopes at the Paranal Observatory in Chile and the Maunakea Observatories in Hawaii. What these observations reveal is sure to tell us much about what will become of our own Milky Way Galaxy someday, when the last of the dust and gas is depleted and all its stars become red giants and long-lived red dwarfs.

Further Reading: University of Hawa’ii News, The Astrophysical Journal Letters