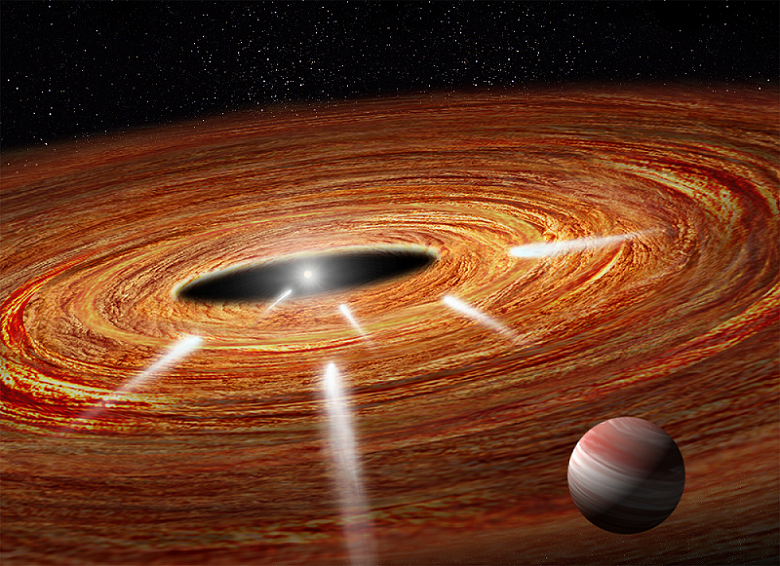

When galaxies collide, all manner of chaos can ensue. Though the process takes millions of years, the merger of two galaxies can result in Supermassive Black Holes (SMBHs, which reside at their centers) merging and becoming even larger. It can also result in stars being kicked out of their galaxies, sending them and even their systems of planets into space as “rogue stars“.

But according to a new study by an international team of astronomers, it appears that in some cases, SMBHs could also be ejected from their galaxies after a merger occurs. Using data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and other telescopes, the team detected what could be a “renegade supermassive black hole” that is traveling away from its galaxy.

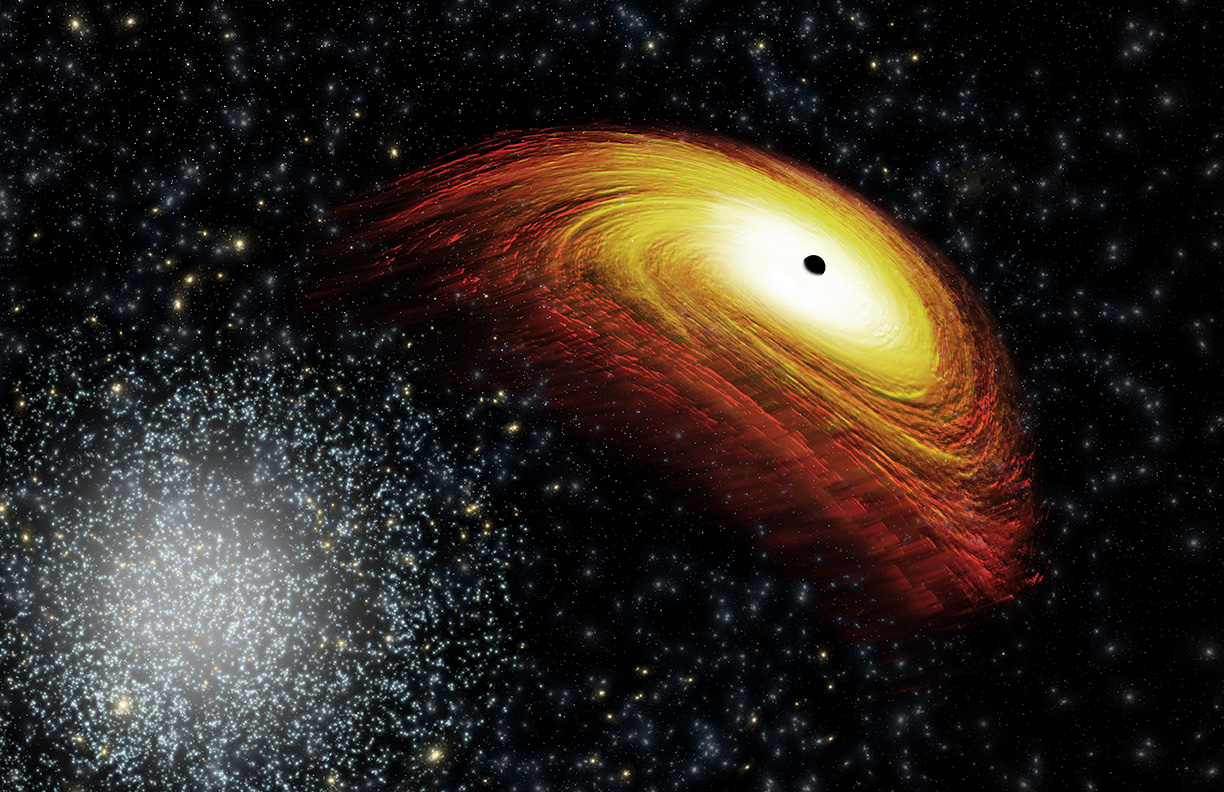

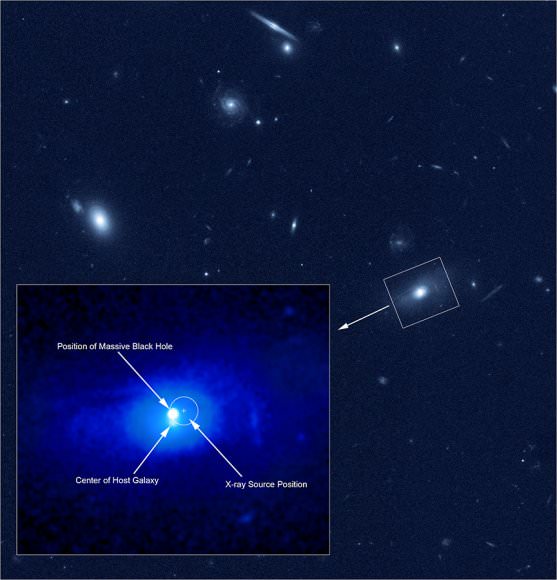

According to the team’s study – which appeared in the Astrophysical Journal under the title A Potential Recoiling Supermassive Black Hole, CXO J101527.2+625911 – the renegade black hole was detected at a distance of about 3.9 billion light years from Earth. It appears to have come from within an elliptical galaxy, and contains the equivalent of 160 million times the mass of our Sun.

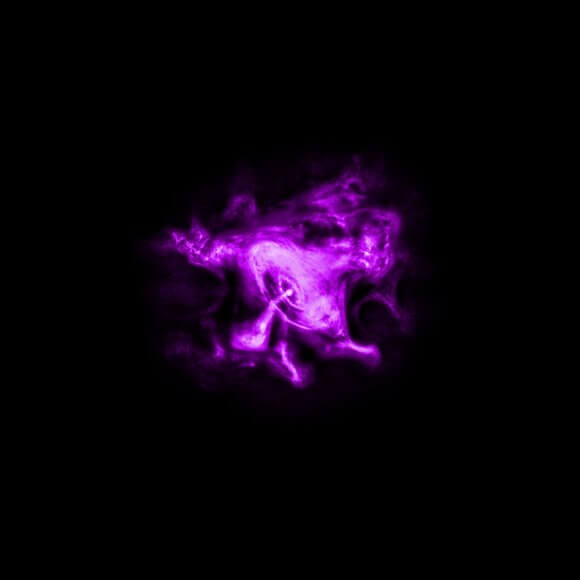

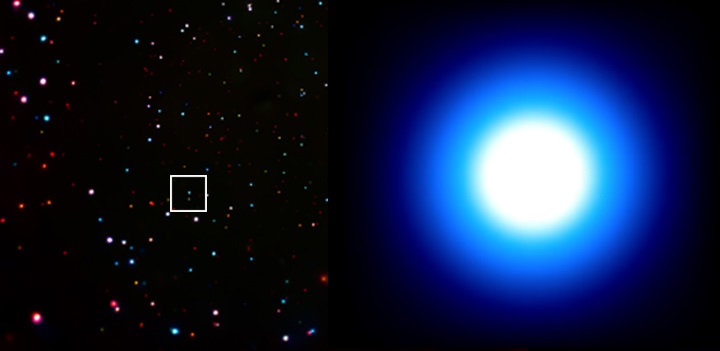

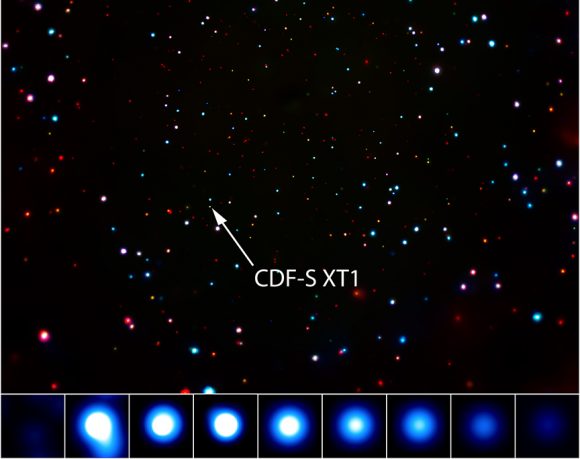

The team found this black hole while searching through thousands of galaxies for evidence of black holes that showed signs of being in motion. This consisted of sifting through data obtained by the Chandra X-ray telescope for bright X-ray sources – a common feature of rapidly-growing SMBHs – that were observed as part of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS).

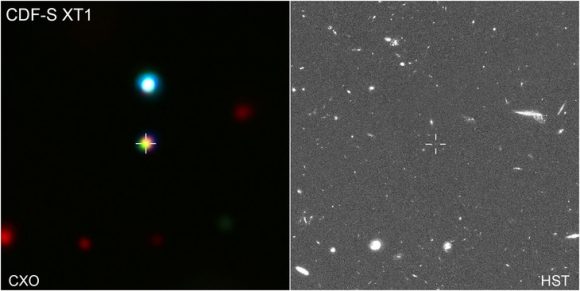

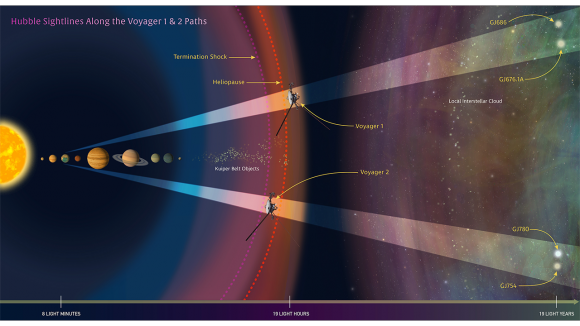

They then looked at Hubble data of all these X-ray bright galaxies to see if it would reveal two bright peaks at the center of any. These bright peaks would be a telltale indication that a pair of supermassive black holes were present, or that a recoiling black hole was moving away from the center of the galaxy. Last, the astronomers examined the SDSS spectral data, which shows how the amount of optical light varies with wavelength.

From all of this, the researchers invariably found what they considered to be a good candidate for a renegade black hole. With the help data from the SDSS and the Keck telescope in Hawaii, they determined that this candidate was located near, but visibly offset from, the center of its galaxy. They also noted that it had a velocity that was different from the galaxy – properties which suggested that it was moving on its own.

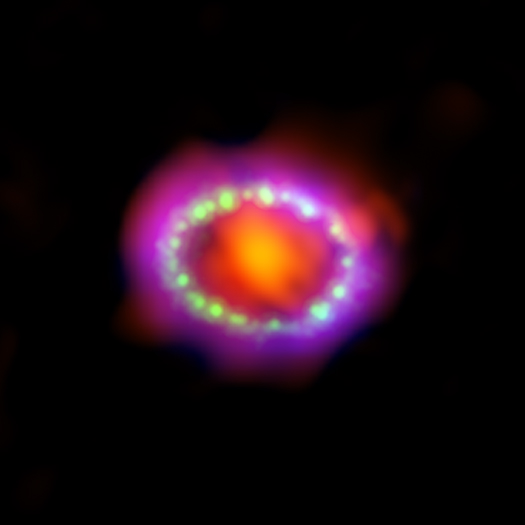

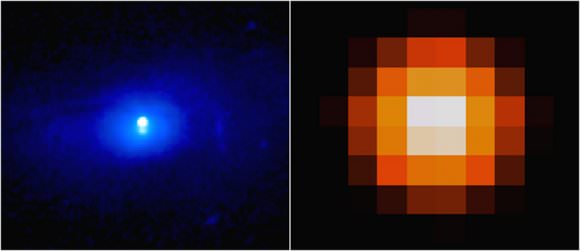

The image below, which was generated from Hubble data, shows the two bright points near the center of the galaxy. Whereas the one on the left was located within the center, the one on the right (the renegade SMBH) was located about 3,000 light years away from the center. Between the X-ray and optical data, all indications pointed towards it being a black hole that was kicked from its galaxy.

In terms of what could have caused this, the team ventured that the back hole might have “recoiled” when two smaller SMBHs collided and merged. This collision would have generated gravitational waves that could have then pushed the black hole out of the galaxy’s center. They further ventured that the black hole may have formed and been set in motion by the collision of two smaller black holes.

Another possible explanation is that two SMBHs are located in the center of this galaxy, but one of them is not producing detectable radiation – which would mean that it is growing too slowly. However, the researchers favor the explanation that what they observed was a renegade black hole, as it seems to be more consistent with the evidence. For example, their study showed signs that the host galaxy was experiencing some disturbance in its outer regions.

This is a possible indication that the merger between the two galaxies occurred in the relatively recent past. Since SMBH mergers are thought to occur when their host galaxies merge, this reservation favors the renegade black hole theory. In addition, the data showed that in this galaxy, stars were forming at a high rate. This agrees with computer simulations that predict that merging galaxies experience an enhanced rate of star formation.

But of course, additional researches is needed before any conclusions can be reached. In the meantime, the findings are likely to be of particular interest to astronomers. Not only does this study involve a truly rare phenomenon – a SMBH that is in motion, rather than resting at the center of a galaxy – but the unique properties involved could help us to learn more about these rare and enigmatic features.

For one, the study of SMBHs could reveal more about the rate and direction of spin of these enigmatic objects before they merge. From this, astronomers would be able to better predict when and where SMBHs are about to merge. Studying the speed of recoiling black holes could also reveal additional information about gravitational waves, which could unlock additional secrets about the nature of space time.

And above all, witnessing a renegade black hole is an opportunity to see some pretty amazing forces at work. Assuming the observations are correct, there will no doubt be follow-up surveys designed to see where the SMBH is traveling and what effect it is having on the surrounding cosmic environment.

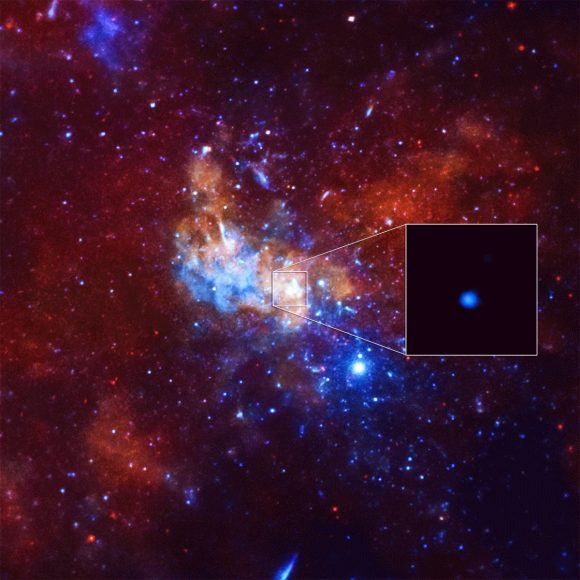

Ever since the 1970s, scientists have been of the opinion that most galaxies have SMBHs at their center. In the years and decades that followed, research confirmed the presence of black holes not only at the center of our galaxy – Sagittarius A* – but at the center of all almost all known massive galaxies. Ranging in mass from the hundreds of thousands to billions of Solar masses, these objects exert a powerful influence on their respective galaxies.

Be sure to enjoy this video, courtesy of the Chandra X-Ray Observatory:

Further Reading: Chandra X-ray Observatory, arXiv