Black holes powering distant quasars in the early Universe grazed on patches of gas or passing galaxies rather than glutting themselves in dramatic collisions according to new observations from NASA’s Spitzer and Hubble space telescopes.

A black hole doesn’t need much gas to satisfy its hunger and turn into a quasar, says study leader Kevin Schawinski of Yale “There’s more than enough gas within a few light-years from the center of our Milky Way to turn it into a quasar,” Schawinski explained. “It just doesn’t happen. But it could happen if one of those small clouds of gas ran into the black hole. Random motions and stirrings inside the galaxy would channel gas into the black hole. Ten billion years ago, those random motions were more common and there was more gas to go around. Small galaxies also were more abundant and were swallowed up by larger galaxies.”

Quasars are distant and brilliant galactic powerhouses. These far-off objects are powered by black holes that glut themselves on captured material; this in turn heats the matter to millions of degrees making it super luminous. The brightest quasars reside in galaxies pushed and pulled by mergers and interactions with other galaxies leaving a lot of material to be gobbled up by the super-massive black holes residing in the galactic cores.

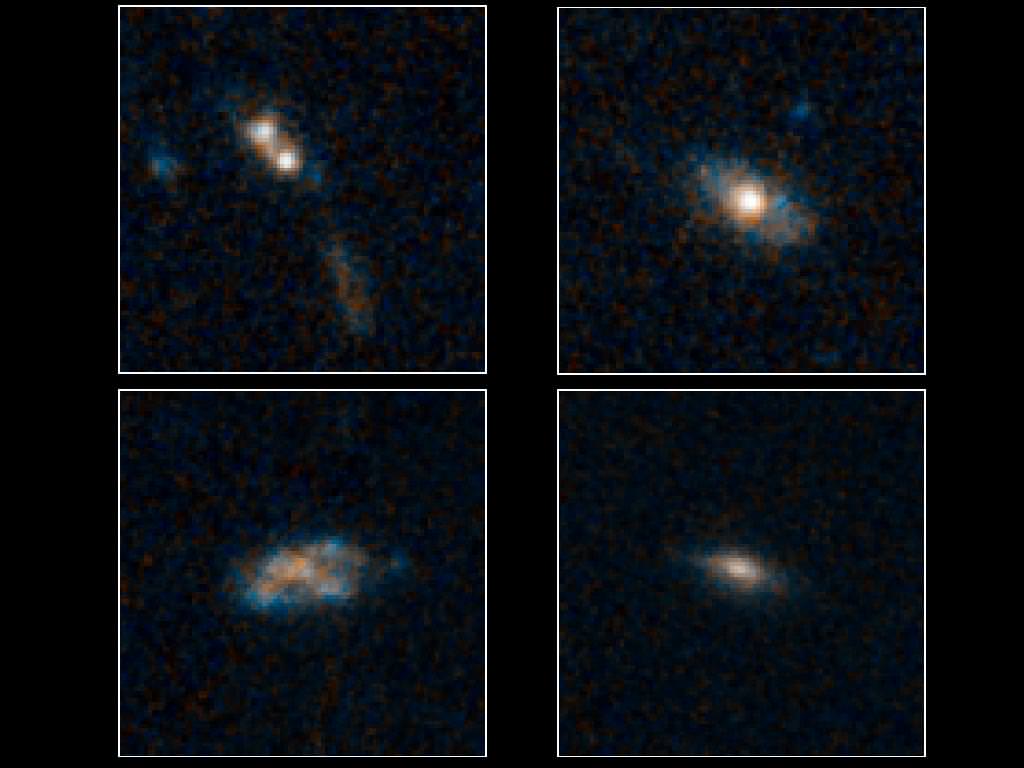

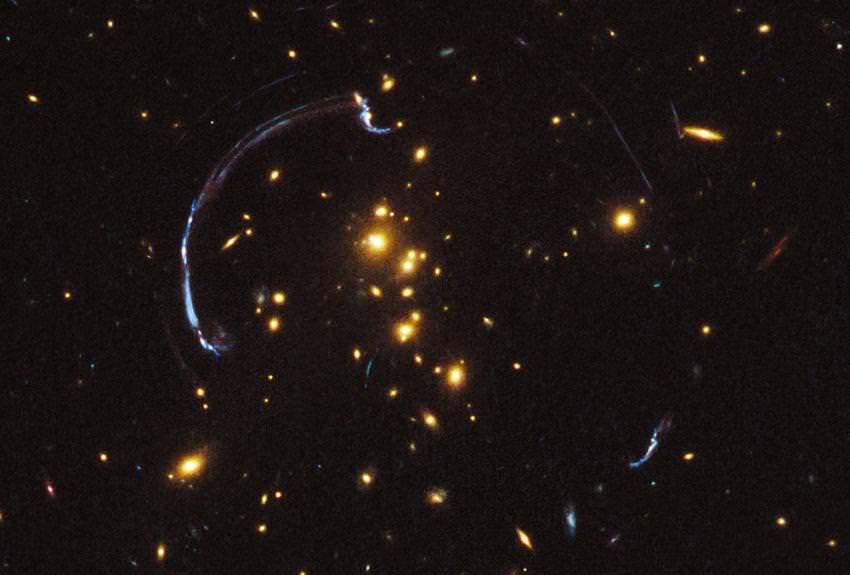

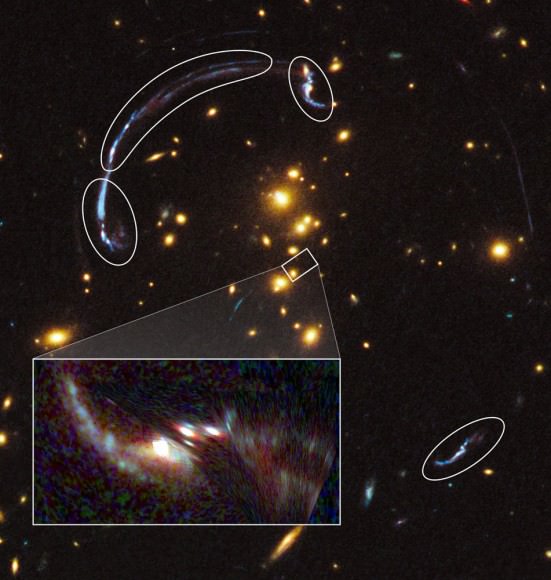

Schawinski and his team studied 30 quasars with NASA’s orbiting telescopes Hubble and Spitzer. These quasars, glowing extremely bright in the infrared images (a telltale sign that resident black holes are actively scooping up gas and dust into their gravitational whirlpool) formed during a time of peak black-hole growth between eight and twelve billion years ago. They found 26 of the host galaxies, all about the size of our own Milky Way Galaxy, showed no signs of collisions, such as smashed arms, distorted shapes or long tidal tails. Only one galaxy in the study showed evidence of an interaction. This finding supports evidence that the creation of the most massive black holes in the early Universe was fueled not by dramatic bursts of major mergers but by smaller, long-term events.

“Quasars that are products of galaxy collisions are very bright,” Schawinski said. “The objects we looked at in this study are the more typical quasars. They’re a lot less luminous. The brilliant quasars born of galaxy mergers get all the attention because they are so bright and their host galaxies are so messed up. But the typical bread-and-butter quasars are actually where most of the black-hole growth is happening. They are the norm, and they don’t need the drama of a collision to shine.

“I think it’s a combination of processes, such as random stirring of gas, supernovae blasts, swallowing of small bodies, and streams of gas and stars feeding material into the nucleus,” Schawinski said.

Unfortunately, the process powering the quasars and their black holes lies below the detection of Hubble making them prime targets for the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope, a large infrared orbiting observatory scheduled for launch in 2018.

You can learn more about the images here.

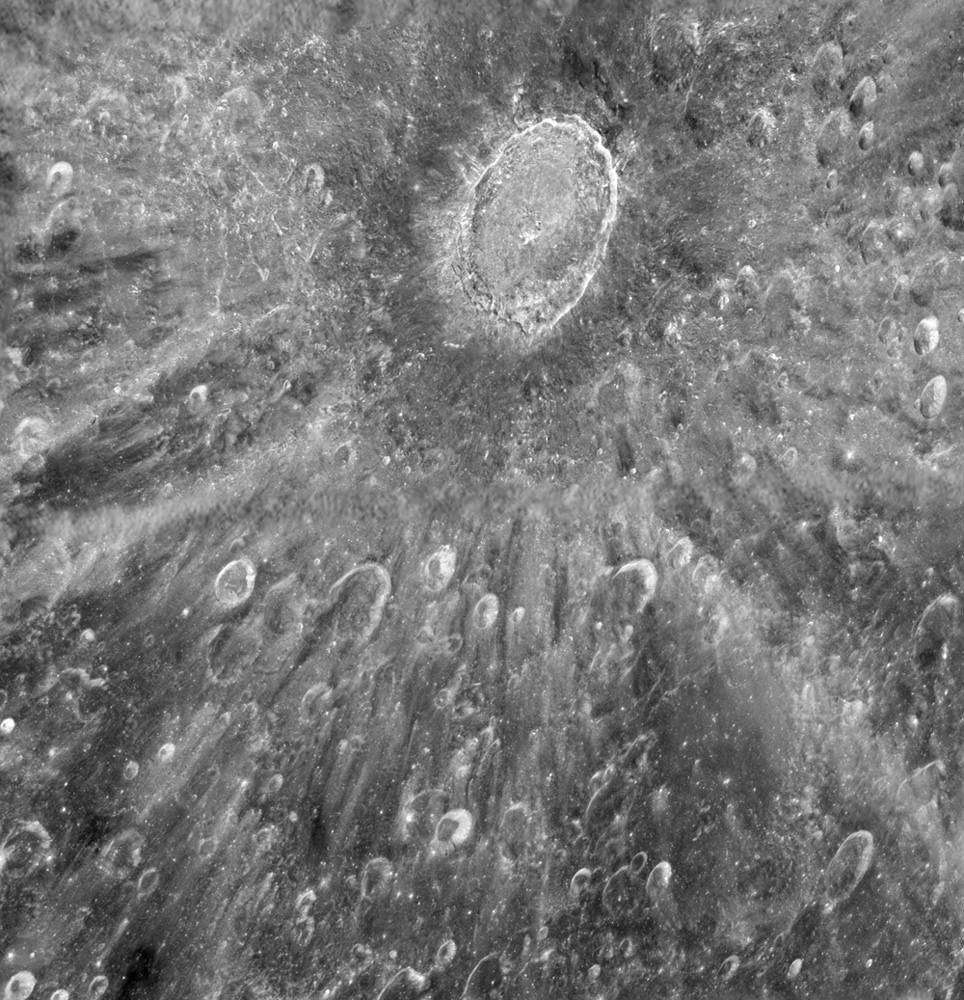

Image caption: These galaxies have so much dust enshrouding them that the brilliant light from their quasars cannot be seen in these images from the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope.