[/caption]

From a NASA press release:

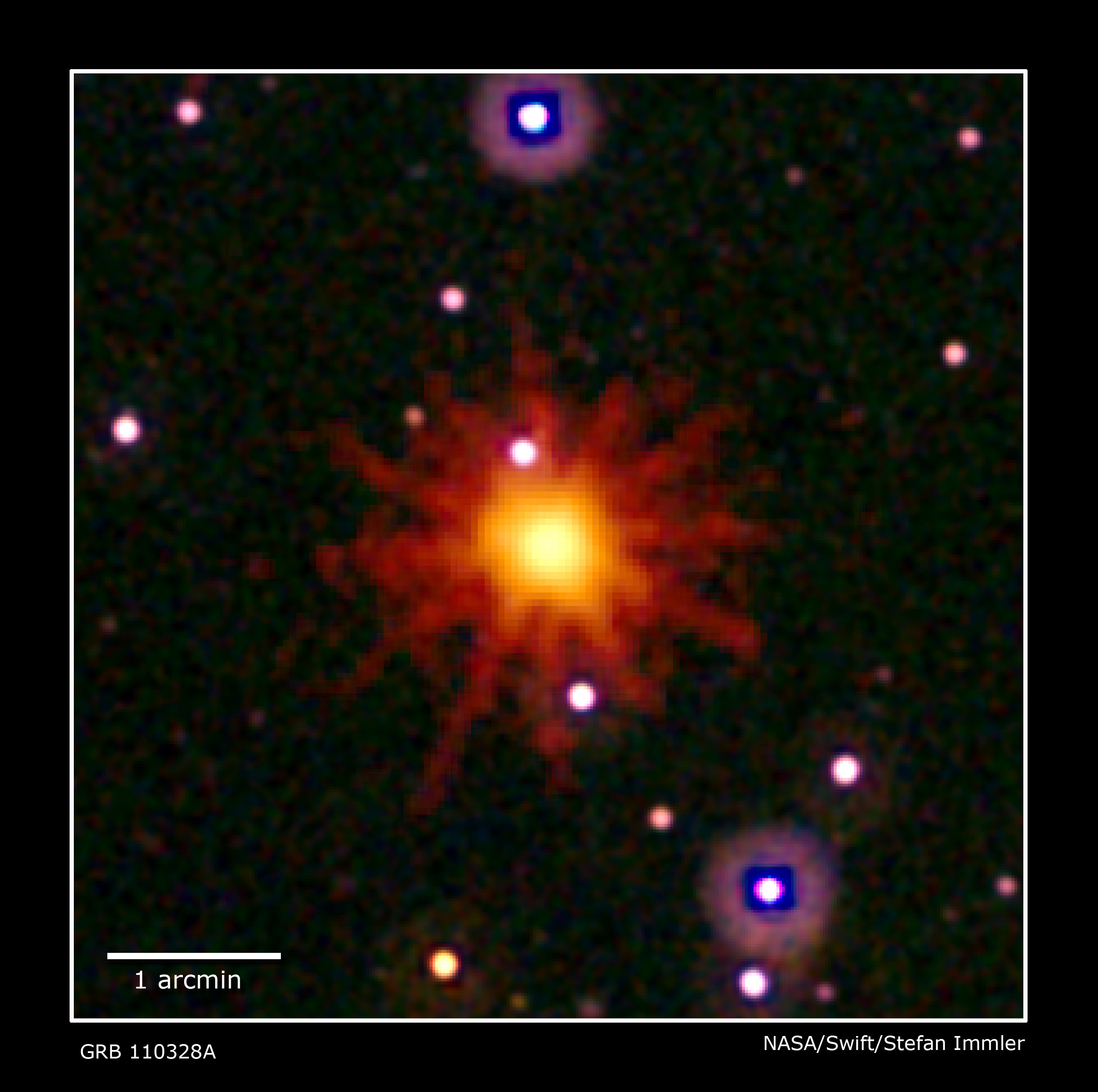

NASA’s Swift, Hubble Space Telescope and Chandra X-ray Observatory have teamed up to study one of the most puzzling cosmic blasts yet observed. More than a week later, high-energy radiation continues to brighten and fade from its location.

Astronomers say they have never seen anything this bright, long-lasting and variable before. Usually, gamma-ray bursts mark the destruction of a massive star, but flaring emission from these events never lasts more than a few hours.

Although research is ongoing, astronomers say that the unusual blast likely arose when a star wandered too close to its galaxy’s central black hole. Intense tidal forces tore the star apart, and the infalling gas continues to stream toward the hole. According to this model, the spinning black hole formed an outflowing jet along its rotational axis. A powerful blast of X- and gamma rays is seen if this jet is pointed in our direction.

On March 28, Swift’s Burst Alert Telescope discovered the source in the constellation Draco when it erupted with the first in a series of powerful X-ray blasts. The satellite determined a position for the explosion, now cataloged as gamma-ray burst (GRB) 110328A, and informed astronomers worldwide.

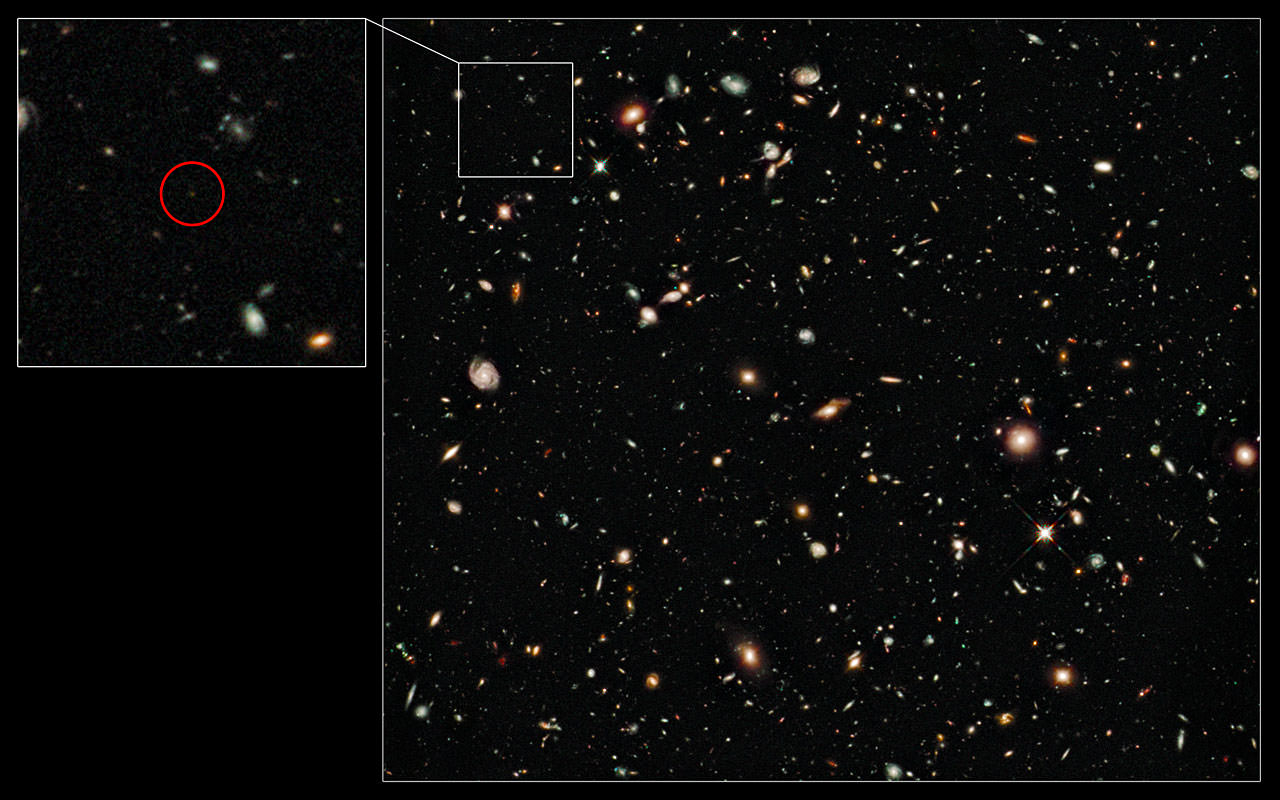

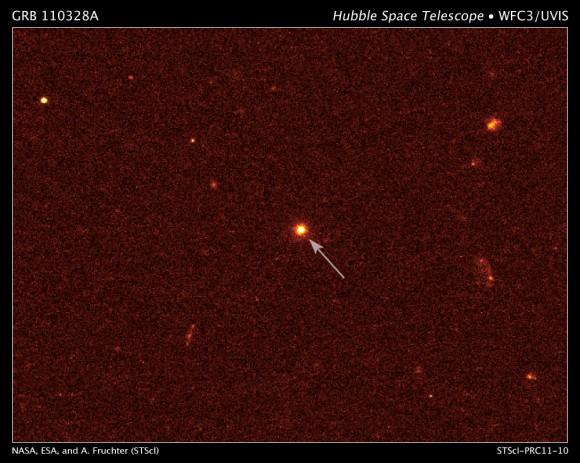

As dozens of telescopes turned to study the spot, astronomers quickly noticed that a small, distant galaxy appeared very near the Swift position. A deep image taken by Hubble on April 4 pinpoints the source of the explosion at the center of this galaxy, which lies 3.8 billion light-years away.

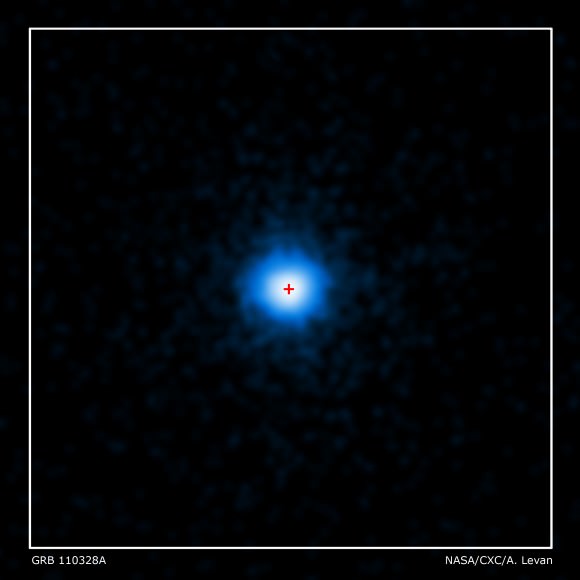

That same day, astronomers used NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory to make a four-hour-long exposure of the puzzling source. The image, which locates the object 10 times more precisely than Swift can, shows that it lies at the center of the galaxy Hubble imaged.

“We know of objects in our own galaxy that can produce repeated bursts, but they are thousands to millions of times less powerful than the bursts we are seeing now. This is truly extraordinary,” said Andrew Fruchter at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore.

“We have been eagerly awaiting the Hubble observation,” said Neil Gehrels, the lead scientist for Swift at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. “The fact that the explosion occurred in the center of a galaxy tells us it is most likely associated with a massive black hole. This solves a key question about the mysterious event.”

Most galaxies, including our own, contain central black holes with millions of times the sun’s mass; those in the largest galaxies can be a thousand times larger. The disrupted star probably succumbed to a black hole less massive than the Milky Way’s, which has a mass four million times that of our sun

Astronomers previously have detected stars disrupted by supermassive black holes, but none have shown the X-ray brightness and variability seen in GRB 110328A. The source has repeatedly flared. Since April 3, for example, it has brightened by more than five times.

Scientists think that the X-rays may be coming from matter moving near the speed of light in a particle jet that forms as the star’s gas falls toward the black hole.

“The best explanation at the moment is that we happen to be looking down the barrel of this jet,” said Andrew Levan at the University of Warwick in the United Kingdom, who led the Chandra observations. “When we look straight down these jets, a brightness boost lets us view details we might otherwise miss.”

This brightness increase, which is called relativistic beaming, occurs when matter moving close to the speed of light is viewed nearly head on.

Astronomers plan additional Hubble observations to see if the galaxy’s core changes brightness.