NASA’s Mars Exploration Program has accomplished some truly spectacular things in the past few decades. Officially launched in 1992, this program has been focused on three major goals: characterizing the climate and geology of Mars, looking for signs of past life, and preparing the way for human crews to explore the planet.

And in the coming years, the Mars 2020 rover will be deployed to the Red Planet and become the latest in a long line of robotic rovers sent to the surface. In a recent press release, NASA announced that it has awarded the launch services contract for the mission to United Launch Alliance (ULA) – the makers of the Atlas V rocket.

The mission is scheduled to launch in July of 2020 aboard an Atlas V 541 rocket from Cape Canaveral in Florida, at a point when Earth and Mars are at opposition. At this time, the planets will be on the same side of the Sun and making their closest approach to each other in four years, being just 62.1 million km (38.6 million miles) part.

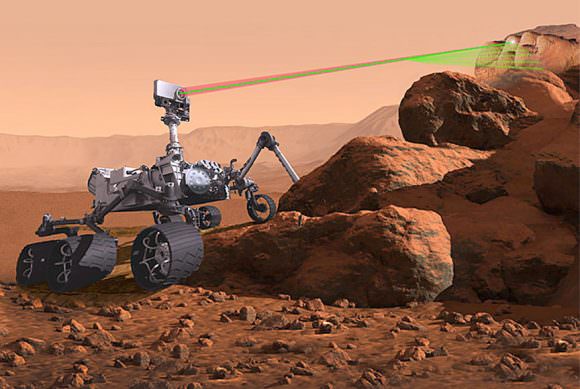

Following in the footsteps of the Curiosity, Opportunity and Spirit rovers, the goal of Mars 2020 mission is to determine the habitability of the Martian environment and search for signs of ancient Martian life. This will include taking samples of soil and rock to learn more about Mars’ “watery past”.

But whereas these and other members of the Mars Exploration Program were searching for evidence that Mars once had liquid water on its surface and a denser atmosphere (i.e. signs that life could have existed), the Mars 2020 mission will attempt to find actual evidence of ancient microbial life.

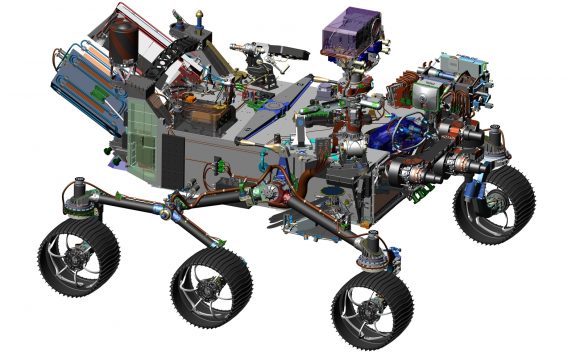

The design of the rover also incorporates several successful features of Curiosity. For instance, the entire landing system (which incorporates a sky crane and heat shield) and the rover’s chassis have been recreated using leftover parts that were originally intended for Curiosity.

There’s also the rover’s radioisotope thermoelectric generator – i.e. the nuclear motor – which was also originally intended as a backup part for Curiosity. But it will also have several upgraded instrument on board that allow for a new guidance and control technique. Known as “Terrain Relative Navigation”, this new landing method allows for greater maneuverability during descent.

Another new feature is the rover’s drill system, which will collect core samples and store them in sealed tubes. These tubes will then be left in a “cache” on the surface, where they will be retrieved by future missions and brought back to Earth – which will constitute the first sample-return mission from the Red Planet.

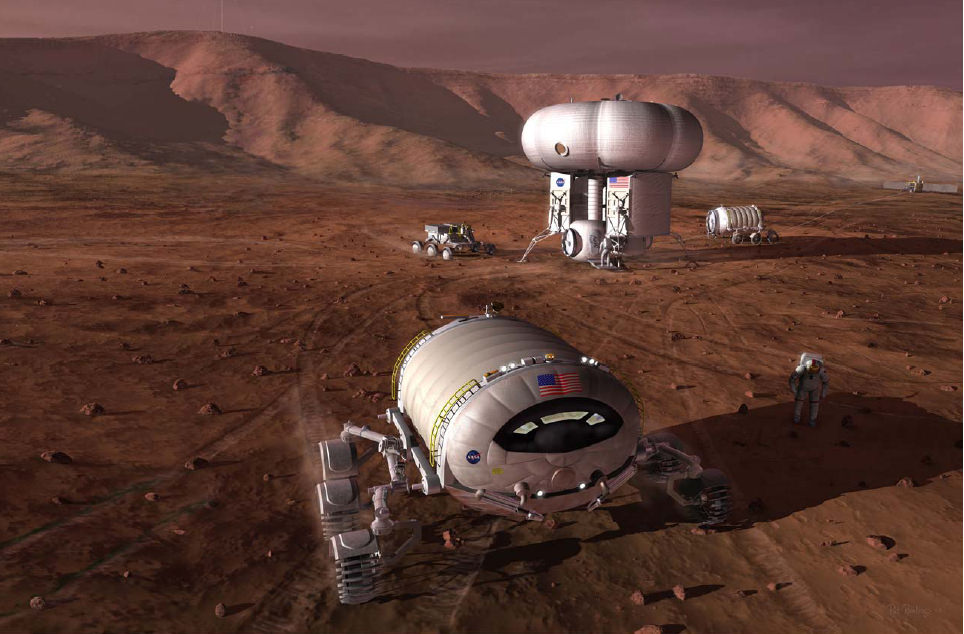

In this respect, Mars 2020 will help pave the way for a crewed mission to the Red Planet, which NASA hopes to mount sometime in the 2030s. The probe will also conduct numerous studies designed to improve landing techniques and assess the planet’s natural resources and hazards, as well as coming up with methods to allow astronauts to live off the environment.

In terms of hazards, the probe will be looking at Martian weather patterns, dust storms, and other potential environmental conditions that will affect human astronauts living and working on the surface. It will also test out a method for producing oxygen from the Martian atmosphere and identifying sources of subsurface water (as a source of drinking water, oxygen, and hydrogen fuel).

As NASA stated in their press release, the Mars 2020 mission will “offer opportunities to deploy new capabilities developed through investments by NASA’s Space Technology Program and Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate, as well as contributions from international partners.”

They also emphasized the opportunities to learn ho future human explorers could rely on in-situ resource utilization as a way of reducing the amount of materials needed to be shipped – which will not only cut down on launch costs but ensure that future missions to the planet are more self-reliant.

The total cost for NASA to launch Mars 2020 is approximately $243 million. This assessment includes the cost of launch services, processing costs for the spacecraft and its power source, launch vehicle integration and tracking, data and telemetry support.

The use of spare parts has also meant reduced expenditure on the overall mission. In total, the Mars 2020 rover and its launch will cost and estimated $2.1 billion USD, which represents a significant savings over previous missions like the Mars Science Laboratory – which cost a total of $2.5 billion USD.

Between now and 2020, NASA also intends to launch the Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport (InSight) lander mission, which is currently targeted for 2018. This and the Mars 2020 rover will be the latest in a long line of orbiters, rovers and landers that are seeking to unlock the mysteries of the Red Planet and prepare it for human visitors!

Further Reading: NASA, Mars 2020 Rover