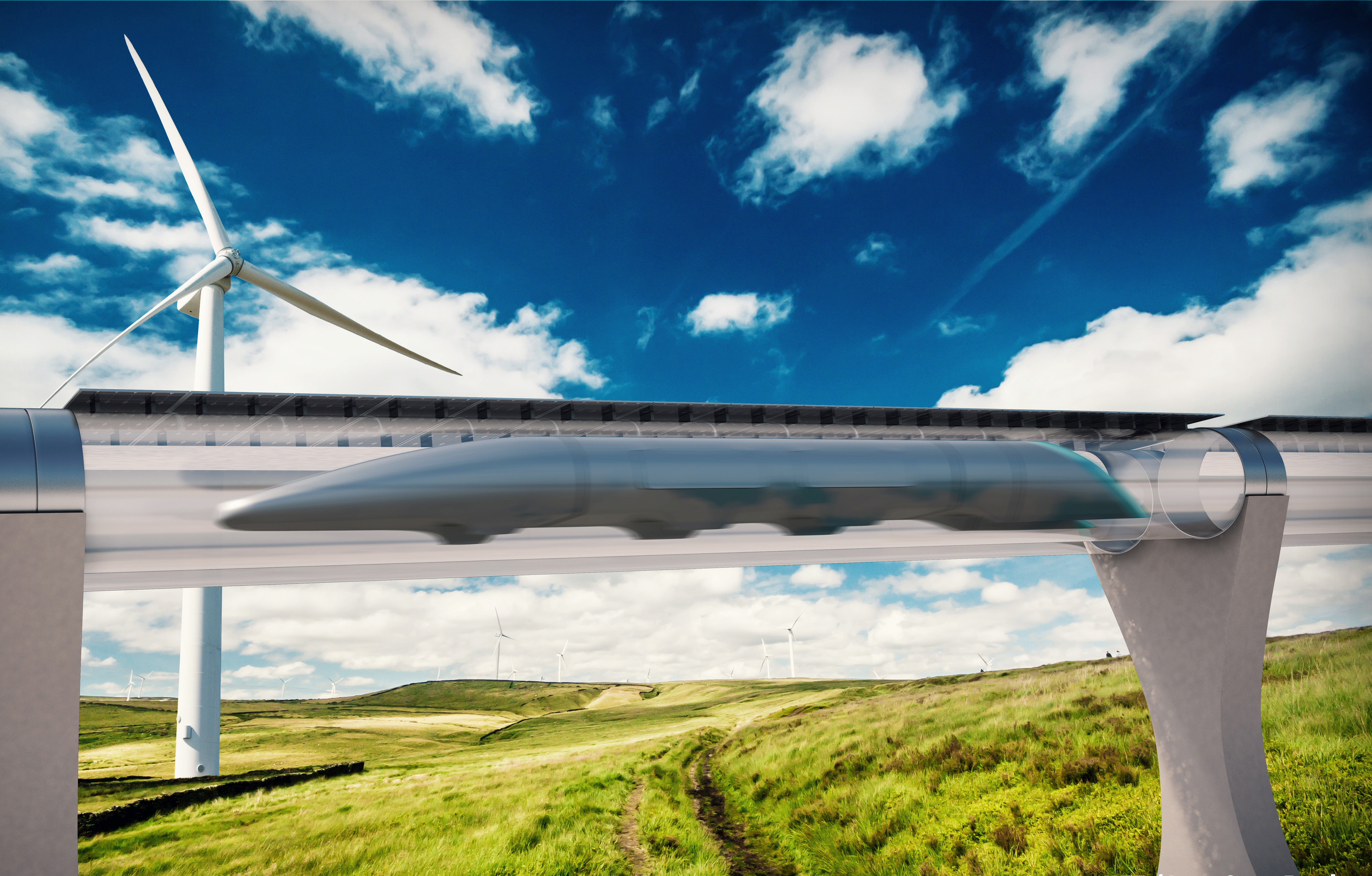

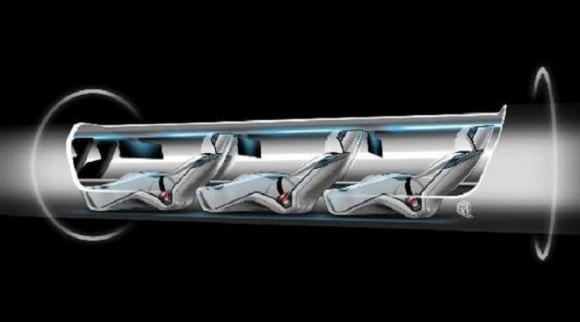

Back in 2012, Tesla Motors, Paypal and SpaceX founder Elon Musk made headlines when he announced his idea for a “fifth form of transportation“. Known as the Hyperloop, the concept called for the creation of a high-speed train that would use a low-pressure steel tube and a series of aluminum pod cars to whisk passengers from San Francisco to Los Angeles in just 35 minutes. At the time, Musk claimed he was simply too busy with other projects to build such a system, but that others were free to take a crack at it.

Since then, two startups have emerged that are attempting to do just that. And just yesterday, the startup known as Hyperloop One (formerly Hyperloop Technologies) conducted a test on their full-scale test track located in the Nevada Desert. In what they referred to as a “Propulsion Open Air Test” (POAT), this startup passed a major developmental milestone, bringing them one step closer to making the dream of the Hyperloop a reality.

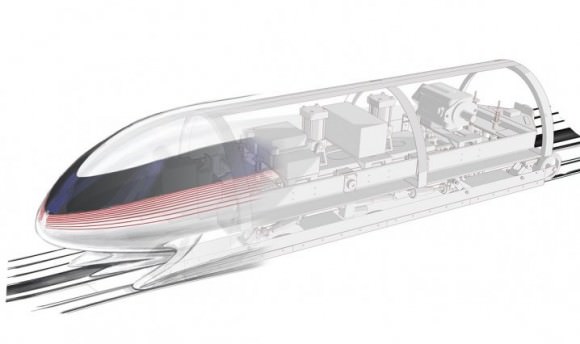

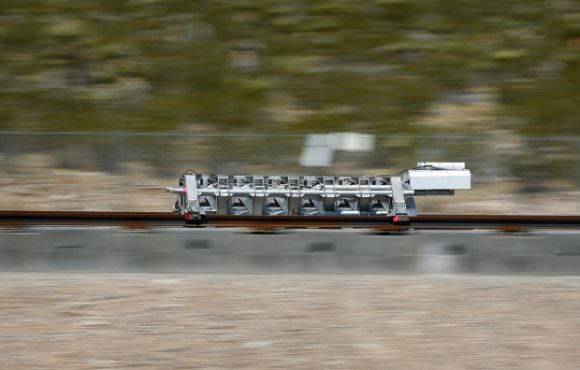

Using the same linear-accelerator motor that will one day propel podcars through a series of semi-pressurized tubes, the Hyperloop One’s engineers managed to accelerate their test vehicle down a rail track at speeds of up to 483 km/h (300 mph) before plowing it into a sand berm. While this is not quite the 1125 km/h (700 mph) that Hyperloop One hopes to get their pods up to (and there are still matter to work out, such as passenger safety) it is a major step forward.

For one, the test provided some valuable returns that showed that the startup’s eventual goal is realizable. Before it slammed into a pile of sand (on a count of the fact that they have yet to design a braking system) the engineers were able to confirm that the test car had managed to accelerate from 0 to 160 km/h (100 mph) in one second. Within a second and a half, the pod had reached 193 km/h (120 mph), reportedly pulling 2.5 Gs in the process.

As Josh Giegel, Hyperloop One’s chief engineer, explained in a recent interview with Mashable, the test addressed their system’s linear electric motor-based propulsion. Their design is distinguished from other motors in that it has no moving parts, relying instead on a series of “blades” that measure roughly 60 centimeters long and 15 wide (24 by 6 inches). When powered, these blades create electromagnetic energy that reacts with the pod to propel it along.

Hyperloop One CEO Rob Lloyd was on hand to comment. By 2020, he hopes to sees three lines in operation, with one likely running between San Fransisco and LA and another potentially in Russia. “This was a major technology milestone,” he said. “Hyperloop is faster, greener, safer, and cheaper than any other mode of transportation… We’re building this thing.”

Lloyd also took the occasion to announce new partnerships that the company is entering into – which include architecture, engineering, finance, freight and tunneling firms – as well as the $80 million in Series B funding they have received. But perhaps the most interesting development to coincide with the test was the decision to change their name. While the reason for this was not explained, the smart money is on it being intended to clear up confusion surrounding the company’s immediate competition.

At present, there are two major companies competing to bring Musk’s vision to life. On the one hand, there is Hyperloop One (formerly Hyperloop Technologies), while the other is Hyperloop Transportation Technologies (or HTT). This little naming scheme has caused quite a bit of confusion in the past, and it is clear at this point that Hyperloop One wants to distinguish itself as being the preeminent leader in the field.

But of course, the competition is far from over. In the past few years, HTT has announced some lucrative partnerships as well, which included signing with international engineering giant Aecom and Oerlikon, the world’s oldest vacuum technology company. Earlier this year, HTT also announced an agreement with the Slovakian government to build two Hyperloops that will connect major cities in Central Europe.

One of these lines will run between Vienna, Austria and Bratislava, Slovakia, while the other will connect Bratislava to Budapest, Hungary. The project is expected to cost $200 – $300 million, and is expected to reach an annual capacity of 10 million passengers.

Last, but not least, it is important to note that Hyperloop One’s test comes not long after the Hyperloop Pod Competition, a design competition sponsored by SpaceX that saw 100 university teams compete to create a design for a Hyperloop podcar. The winning team, which hails from MIT, will be testing their final prototype podcar on the one-mile Hyperloop Test Track at SpaceX’s headquarters in California next month.

Much is happening on the Hyperloop front! Who knows where it will all lead? One thing is clear though. Since Musk released the white paper for his concept in 2013 and companies began picking it up, this project has had no shortage of enthusiasts, skeptics and detractors. With every passing milestone, partnership and test, more and more people are beginning to seriously ask, “can it be done?”