Days like these make being an astrophysicist interesting. On the one hand, there is the annoucement of BICEP2 that the long-suspected theory of an inflationary big bang is actually true. It’s the type of discovery that makes you want to grab random people off the street and tell them what an amazing thing the Universe is. On the other hand, this is exactly the type of moment when we should be calm, and push back on the claims made by one research team. So let’s take a deep breath and look at what we know, and what we don’t.

First off, let’s dispel a few rumors. This latest research is not the first evidence of gravitational waves. The first indirect evidence for gravitational waves was found in the orbital decay of a binary pulsar by Russell Hulse and Joseph Taylor, for which they were awarded the Nobel prize in 1993. This new work is also not the first discovery of polarization within the cosmic microwave background, or even the first observation of B-mode polarization. This new work is exciting because it finds evidence of a specific form of B-mode polarization due to primordial gravitational waves. The type of gravitational waves that would only be caused by inflation during the earliest moments of the Universe.

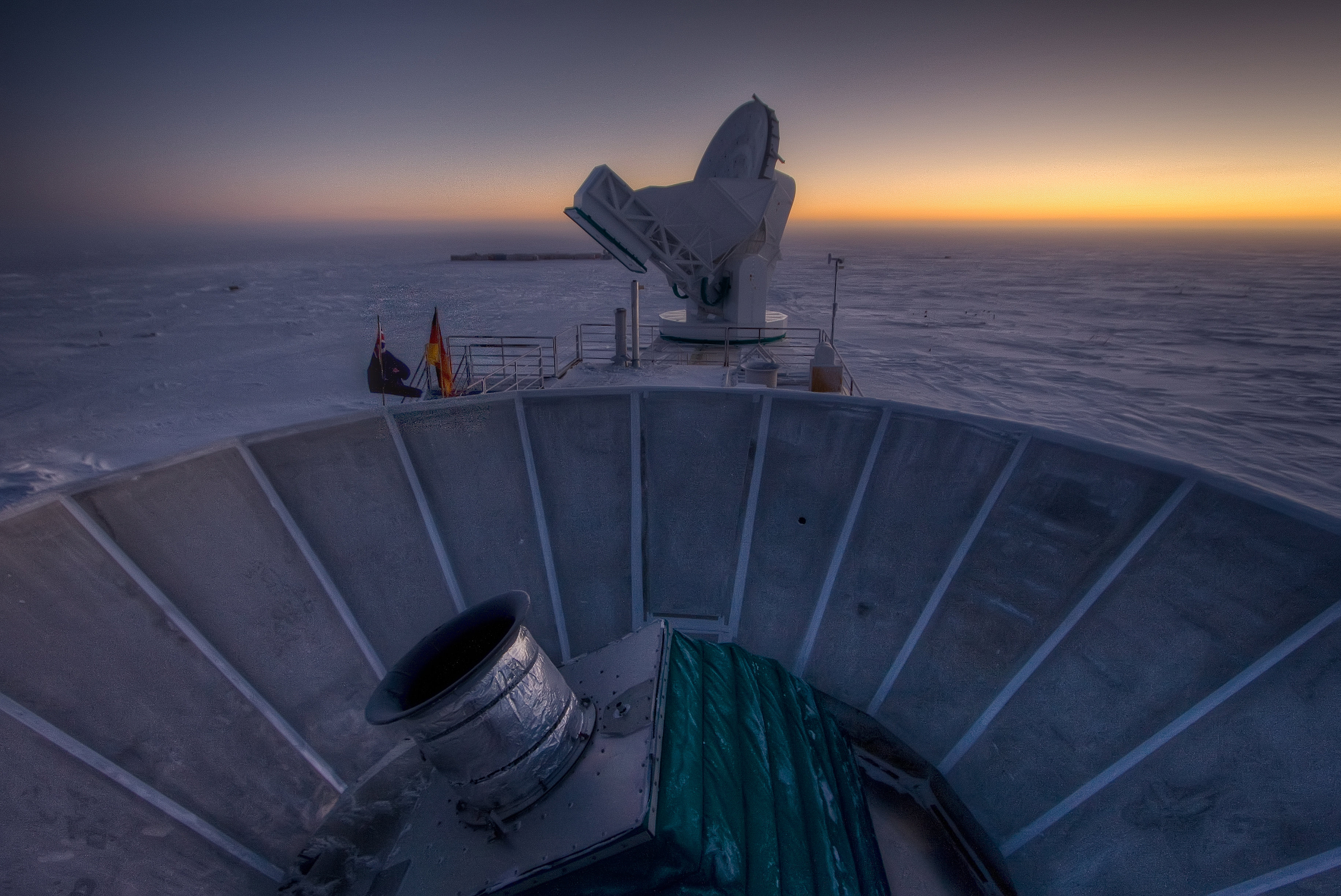

It should also be noted that this new work hasn’t yet been peer reviewed. It will be, and it will most likely pass muster, but until it does we should be a bit cautious about the results. Even then these results will need to be verified by other experiments. For example, data from the Planck space telescope should be able to confirm these results assuming they’re valid.

That said, these new results are really, really interesting.

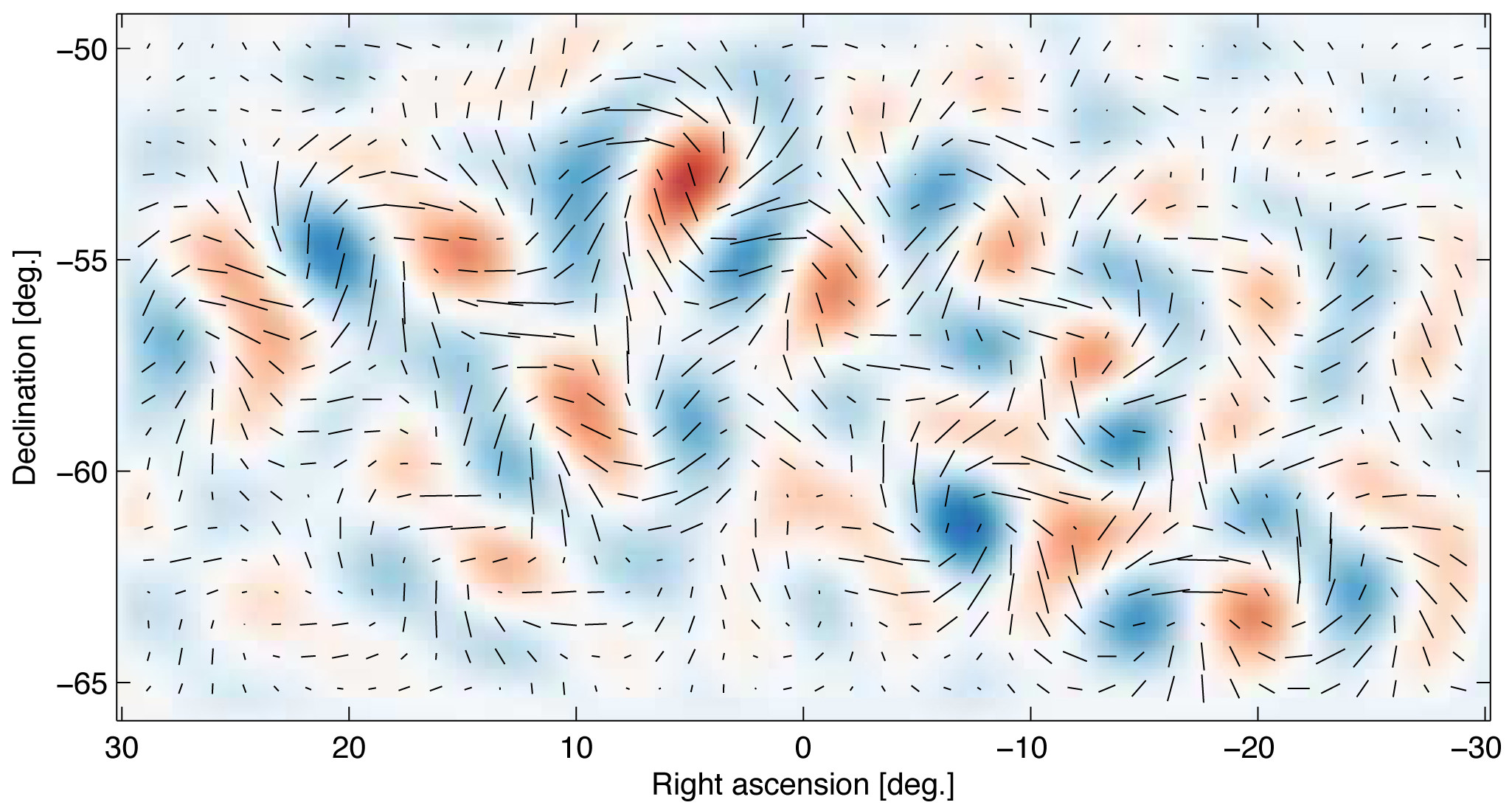

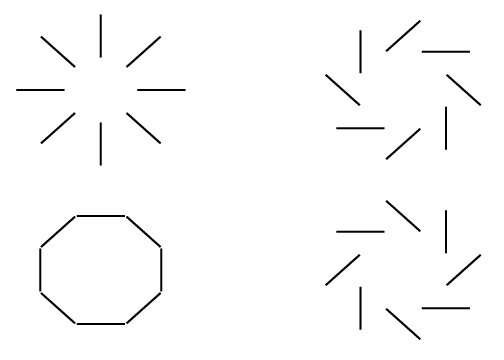

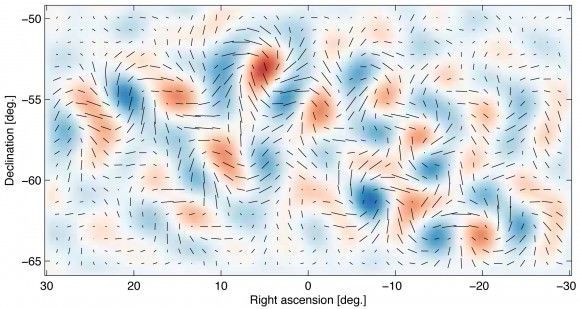

What the team did was to analyze what is known as B-mode polarization within the cosmic microwave background (CMB). Light waves oscillate perpendicular to their direction of motion, similar to the way water waves oscillate up and down while they travel along the surface of water. This means light can have an orientation. For light from the CMB, this orientation has two modes, known as E and B. The E-mode polarization is caused by temperature fluctuations in the CMB, and was first observed in 2002 by the DASI interferometer.

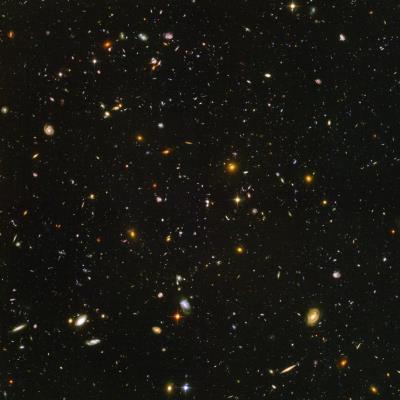

The B-mode polarization can occur in two ways. The first way is due to gravitational lensing. The first is due to gravitational lensing of the E-mode. The cosmic microwave background we see today has travelled for more than 13 billion years before reaching us. Along its journey some of it has passed close enough to galaxies and the like to be gravitationally lensed. This gravitational lensing twists the polarization a bit, giving some of it a B-mode polarization. This type was first observed in July of 2013. The second way is due to gravitational waves from the early inflationary period of the universe. As inflationary period occurred, then it produced gravitational waves on a cosmic scale. Just as the gravitational lensing produces B-mode polarization, these primordial gravitational waves produce a B-mode effect. The discovery of primordial wave B-mode polarization is what was announced today.

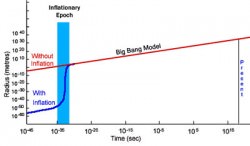

Inflation has been proposed as a reason for why the cosmic microwave background is as uniform as it is. We see small fluctuations in the CMB, but not large hot or cold spots. This means the early Universe must have been small enough for temperatures to even out. But the CMB is so uniform that the observable universe must have been much smaller than predicted by the big bang. However, if the Universe experienced a rapid increase in size during its early moments, then everything would work out. The only problem was we didn’t have any direct evidence of inflation.

Assuming these new results hold up, now we do. Not only that, we know that inflation was stronger than we anticipated. The strength of the gravitational waves is measured in a value known as r, where larger is stronger. It was found that r = 0.2, which is much higher than anticipated. Based upon earlier results from the Planck telescope, it was expected that r < 0.11. So there seems to be a bit of tension with earlier findings. There are ways in which this tension can be resolved, but just how is yet to be determined.

So this work still needs to be peer reviewed, and it needs to be confirmed by other experiments, and then the tension between this result and earlier results needs to be resolved. There is still much to do before we really understand inflation. But overall this is really big news, possibly even Nobel prize worthy. The results are so strong that it seems pretty clear we have direct evidence of cosmic inflation, which is a huge step forward. Before today we only had physical evidence back to when the universe was about a second old, at a time when nucleosynthesis occurred. With this new result we are now able to probe the Universe when it was less than 10 trillion trillion trillionths of a second old.

Which is pretty amazing when you think about it.