[/caption]

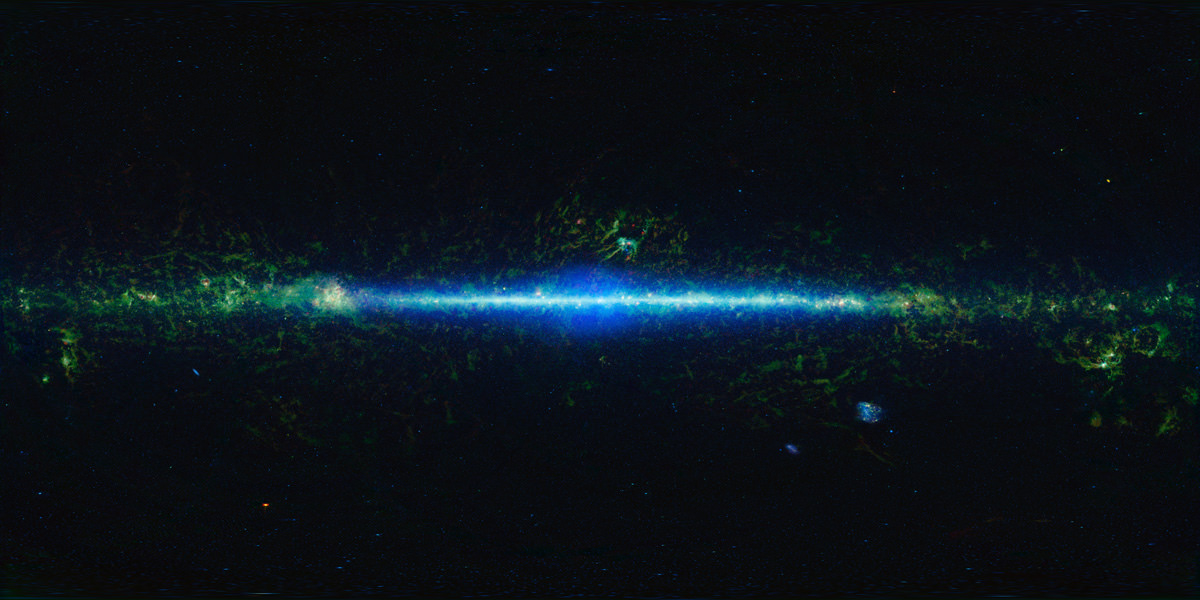

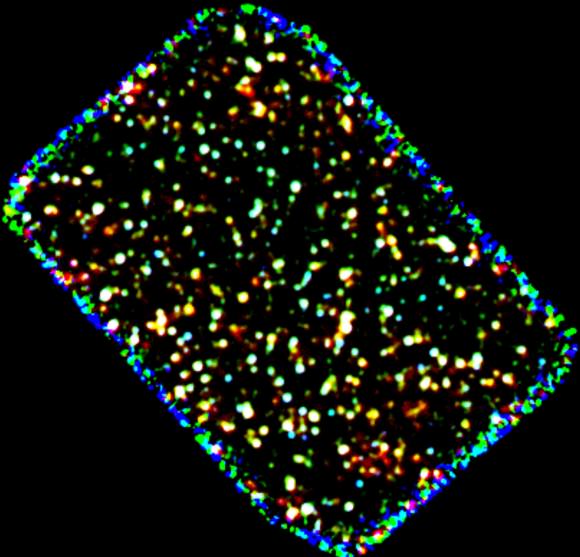

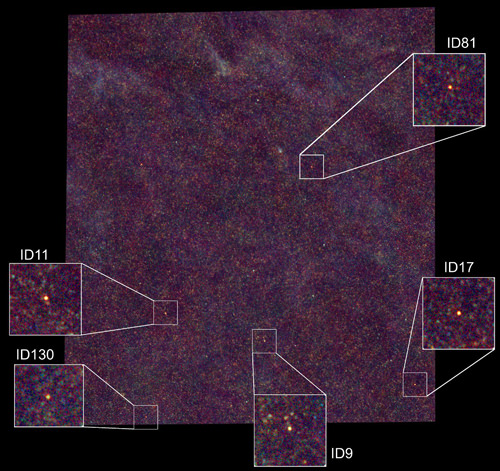

Love all the great things you can see in infrared? Then zoom on into the big view of the entire sky from the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) mission. WISE has collected more than 15 trillion bytes of data with 2.7 million images of the sky at infrared light. It’s captured everything from nearby asteroids to distant galaxies, finding “Y-dwarfs,” a Trojan asteroid sharing Earth’s orbit, and stars and galaxies that had never been seen before, as well as showing astronomers that there are significantly fewer mid-size asteroids than previously thought.

Today NASA released a new atlas and catalog of the entire sky in infrared, and now even more discoveries are expected since anyone can have access to the whole sky as seen by the spacecraft.

“With the release of the all-sky catalog and atlas, WISE joins the pantheon of great sky surveys that have led to many remarkable discoveries about the universe,” said Roc Cutri, who leads the WISE data processing and archiving effort at the Infrared and Processing Analysis Center at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. “It will be exciting and rewarding to see the innovative ways the science and educational communities will use WISE in their studies now that they have the data at their fingertips.”

Thanks to John Williams at Starry Critters, you can now zoom into WISE’s entire map of the infrared sky. John notes some interesting things in the image: “The bright swath across the center is the Milky Way Galaxy; our home galaxy. The view is toward the center of the galaxy with the spiral arms stretching to the edges. Some artifacts were left in such as bright red spots off the plane of the galaxy. These are Saturn, Jupiter and Mars.”

An introduction and quick guide to accessing the WISE all-sky archive for astronomers is online at: http://wise2.ipac.caltech.edu/docs/release/allsky/

Click here for a collection of WISE images released to date.