The ‘Language in the Cosmos’ symposium

Three times in October, 2017 researchers turned a powerful radar telescope near Tromsø, Norway towards an invisibly faint star in the constellation Canis Minor (the small dog) and beamed a coded message into space in an attempt to signal an alien civilization. This new attempt to find other intelligent life in the universe was reported in a presentation at the ‘Language in the Cosmos’ symposium held on May 26 in Los Angeles, California.

METI International sponsored the symposium. This organization was founded to promote messaging to extraterrestrial intelligence (METI) as a new approach to in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI). It also supports other aspects of SETI research and astrobiology. The symposium was held as part of the International Space Development Conference sponsored by the National Space Society. It brought together linguists and other scientists for a daylong program of 11 presentations. Dr. Sheri Wells-Jensen, who is a linguist from Bowling Green State University in Ohio, was the organizer.

This is the second of a two part series about METI International’s symposium. It will focus on a presentation given at the symposium by the president of METI International, Dr. Douglas Vakoch. He spoke about a project that hasn’t previously gotten much attention: the first attempt to send a message to a nearby potentially habitable exoplanet, GJ273b. Vakoch led the team that constructed the tutorial portion of the message.

Message to the stars

The modern search for extraterrestrial intelligence began in 1960. This is when astronomer Frank Drake used a radio telescope in West Virginia to listen for signals from two nearby stars. Astronomers have sporadically mounted increasingly sophisticated searches, when funding has been available. The largest current project is Breakthrough Listen, funded by billionaire Yuri Milner. Searches have been made for laser as well as radio signals. Researchers have also looked for the megastructures that advanced aliens might create in space near their stars. METI International advocates an entirely new approach in which messages are transmitted to nearby stars in hopes of eliciting a reply.

The project to send a message to GJ273b was a collaboration between artists and scientists. It was initiated by the organizers of the Sónar Music, Creativity, and Technology Festival. The Sónar festival has been held every year since 1994 in Barcelona, Spain. The organizers wanted to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the festival. To implement the project, the festival organizers sought the help of the Catalonia Institute of Space Studies (IEEC), and METI International.

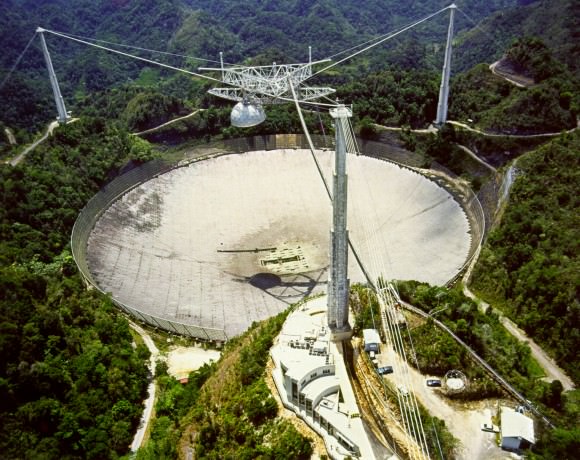

To transmit the message, the team turned to The European Incoherent Scatter Scientific Association (EISCAT) which operates a network of radio and radar telescopes in Finland, Norway, and Sweden. This network is primarily used to study interactions between the sun and Earth’s ionosphere and magnetic field from a vantage point north of the arctic circle. The message was transmitted from a 32 meter diameter steerable dish at EISCAT’s Ramfjordmoen facility near Tromso, Norway, with a peak power of 2 megawatts. It is the first interstellar message ever to be sent towards a known potentially habitable exoplanet.

The target system

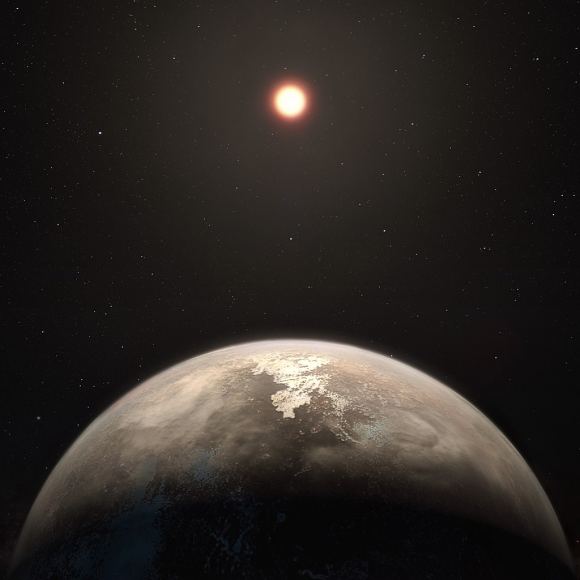

The obscure star known by the catalogue designation GJ273 caught the attention of the Dutch-American astronomer Willem J. Luyten in 1935. Luyten was researching the motions of the star. The star caught his attention because it was moving through Earth’s sky at the surprising rate of 3.7 arc seconds per year. Later study showed that this fast apparent motion is due to the fact that GJ273 is one of the sun’s nearest neighbors, just 12.4 light years away. It is the 24th closest star to the sun. Because of Luyten’s discovery it is sometimes known as Luyten’s star.

Luyten’s star is a faint red dwarf star with only a quarter of the sun’s mass. It caught astronomers’ attention again in March 2017. That’s when an exoplanet, GJ273b, was discovered in it’s habitable zone. The habitable zone is the range of distances where a planet with an atmosphere similar to Earth’s would, theoretically, have a range of temperatures suitable to have liquid water on its surface. The planet is a super Earth, with a mass 2.89 times that of our homeworld. It orbits just 800,000 miles from its faint sun, which it circles every 18 Earth days.

This exoplanet was chosen because of its proximity to Earth, and because it is visible in the sky from the transmitter’s northerly location. Because GJ273b is relatively nearby, and radio messages travel at the speed of light, a reply from the aliens could come as early as the middle of this century.

The Message

Comparisons with Voyager

The GJ273b transmission is not the first time a message intended for extraterrestrials has been sent into space. Probably the most familiar interstellar message is the one carried on board the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft. NASA launched these interplanetary robots in 1977. They traveled on trajectories that hurtled them into interstellar space after they completed their missions to explore the outer solar system.

The message carried aboard each Voyager spacecraft was encoded digitally on a phonographic record. It was largely pictorial, and attempted to give a comprehensive overview of humans and Earth. It also included a selection of music from various Earthly cultures. These spacecraft will take tens of thousands of years to reach the stars. So, no reply can be expected on a timescale relevant to our society.

In some ways the GJ273b message is very different from the Voyager message. Unlike the Voyager record, it isn’t pictorial and doesn’t attempt to give a comprehensive overview of humans and Earth. This is perhaps because, unlike the Voyager message, it is intended to initiate a dialog on a timescale of decades. It resembles the Voyager message in that it contains music from Earth, namely, music from the artists that performed at the Sónar music festival.

Saying hello

For the human reader, understanding the message is a bit more of a challenge than looking at the pictures encoded on the Voyager record. You can try your hand at decoding the message yourself, because the organizers posted the whole thing on their website. Be forewarned that if you continue reading here, there are spoilers (or helpful clues, depending on how you look at it).

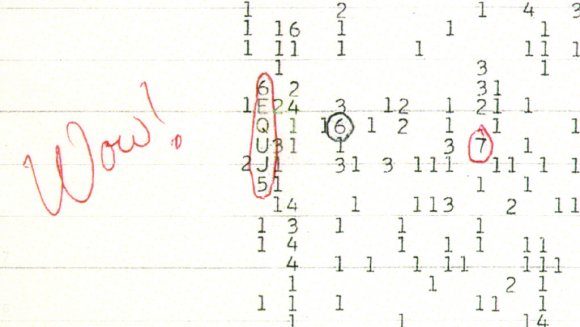

The message consists of a string of binary digits—ones and zeros. These are represented in the signal by a shift between two slightly different radio frequencies. The ‘hello’ section is designed to catch the attention of alien listeners. It consists of a string of prime numbers (numbers divisible only by themselves and one). They are represented with binary digits like this:

01001100011100000111110000000000011111111111

The message continues the sequence up to 193. A signal like this almost certainly can’t be produced by natural processes, and can only be the designed handiwork of beings who know math.

The tutorial

After the ‘hello’ section comes the tutorial. This, and all the rest of the message, uses eight bit blocks of binary digits as the basis for its symbols. The tutorial begins by introducing number symbols by counting. It uses base two numbers like this:

10000000 (0) 10000001 (1) 10000010 (2) 10000011 (3)

10000100 (4) 10000101 (5) 10000110 (6) 10000111 (7)

10001000 (8) 10001001 (9) 10001010 (10)

The leading ‘1’ allows numbers to be distinguished from other 8 bit symbols that don’t represent numbers.

After counting, the tutorial introduces symbols for the operations of arithmetic by showing sample problems. Here’s a sampling of some of the symbols for math operations:

00000110 (+) 00000111 (-) 00001000 (×) 00001001 (÷)

00111100 (=)

The tutorial then proceeds to geometry using combinations of numbers and symbols to illustrate the Pythagorean theorem. It eventually progresses to sine waves, thereby describing the radio wave carrying the signal itself. Finally the tutorial describes the physics of sound waves and the relationships between musical notes.

Besides the numbers, the tutorial introduces 55 8-bit symbols in all. It provides the instructions that aliens would need to properly reproduce a series of digitally encoded musical selections from the Sónar Festival.

During its journey of 70 trillion miles, the message is sure to become corrupted with noise. To compensate, the tutorial was transmitted three times during each transmission, requiring a total of 33 minutes to transmit. The entire transmission was repeated on three separate days, October 16, 17, and 18, 2017. A second block of three transmissions was made on May 14, 15, and 16, 2018.

The music

Each transmission included a different selection of music, with the works of 38 different musicians included in all. You can hear recordings of all this music at the Sónar Calling GJ273b website.

The rationale behind the message

Current and past SETI projects conducted by astronomers here on Earth assume that advanced aliens would make things easy for newly emerging civilizations by establishing powerful beacons that would broadcast in all directions at all times. Thus, SETI searchers generally use the same sort of highly directional dish antennae often used for other research in radio astronomy. They listen to any one star for only a few minutes, searching each one in turn for the beacon.

Unlike the always-on beacons imagined as the objects of Earth’ SETI searches, the Sónar message was only transmitted for 33 minutes on each of three days, and on only two occasions. Vakoch admits that “our message would likely be undetected by a civilization on GJ273b using the same strategy” favored by beacon searching SETI researchers on Earth.

However, some researchers have called traditional SETI assumptions and strategy into question, and studies of alternative search technologies have already been conducted. Vakoch notes that “we humans already have the technological capacity, and need only the funding, to conduct an all-sky survey that would detect intermittent transmission like ours”.

A larger problem is that the message was directed at just one planet. Although GJ273b orbits within its star’s habitable zone, we really know little what that means for whether the planet is actually habitable, or whether it has life or intelligence. Earth itself has been habitable for billions of years. But it has only had a civilization capable of radio transmissions for a century.

Vakoch conceded that “The only way we will get a reply back from GJ273b is if the galaxy is chock full of intelligent life, and it is out there just waiting for us to take the initiative. More realistically, we may need to replicate this process with hundreds, thousands, or even millions of stars before we reach one with an advanced civilization that can detect our signal”. METI International aims to conduct a design study for such a large scale METI project in hopes that funding will materialize from governmental or other sources.

References and further reading:

Cain F. (2013) How could we find aliens, Universe today.

Patton, P. E. (2018) Language in the Cosmos I: Is universal grammar really universal?, Universe Today.

Patton P. E. (2016) Alien Minds, I. Are extraterrestrial civilizations likely to evolve, II. Do aliens think big brains are sexy too?, III. The octopus’s garden and the country of the blind, Universe Today

Patton, P. E. (2015) Who speaks for Earth? The controversy over interstellar messaging, Universe Today.

Patton P. E. (2014) Communicating across the cosmos. Part 1: Shouting into the darkness, Part 2: Petabytes from the stars, Part 3: Bridging the vast gulf, Part 4: Quest for a Rosetta Stone, Universe Today.

Vakoch D. A. (2017) New keys to help extraterrestrials unlock our messages, Scientific American, Observations.

Vakoch D. A. (2011) Responsibility, capability and Active SETI: Policy, law, ethics, and communication with extraterrestrial intelligence, Acta Astronautica, 68:512-519

Vakoch D. A. (2010) An iconic approach to communicating musical concepts in interstellar messages, Acta Astronautica, 67:1406-1409