It has been thought that the existence of plate tectonics has been a significant factor in the shaping of our planet and the evolution of life. Mars and Venus don’t experience such movements of crustal plates but then the differences between the worlds is evident. The exploration of exoplanets too finds many varied environments. Many of these new alien worlds seem to have significant internal heating and so lack plate movements too. Instead a new study reveals that these ‘Ignan Earths’ are more likely to have heat pipes that channel magma to she surface. The likely result is a surface temperature similar to Earth in its hottest period when liquid water started forming.

Continue reading “Planets Without Plate Tectonics Could Still Be Habitable”New Research Suggests Io Doesn’t Have a Shallow Ocean of Magma

Jupiter’s moon Io is the most volcanically active body in the Solar System, with roughly 400 active volcanoes regularly ejecting magma into space. This activity arises from Io’s eccentric orbit around Jupiter, which produces incredibly powerful tidal interactions in the interior. In addition to powering Io’s volcanism, this tidal energy is believed to support a global subsurface magma ocean. However, the extent and depth of this ocean remains the subject of debate, with some supporting the idea of a shallow magma ocean while others believe Io has a more rigid, mostly solid interior.

In a recent NASA-supported study, an international team of researchers combined data from multiple missions to measure Io’s tidal deformation. According to their findings, Io does not possess a magma ocean and likely has a mostly solid mantle. Their findings further suggest that tidal forces do not necessarily lead to global magma oceans on moons or planetary bodies. This could have implications for the study of exoplanets that experience tidal heating, including Super-Earths and exomoons similar to Io that orbit massive gas giants.

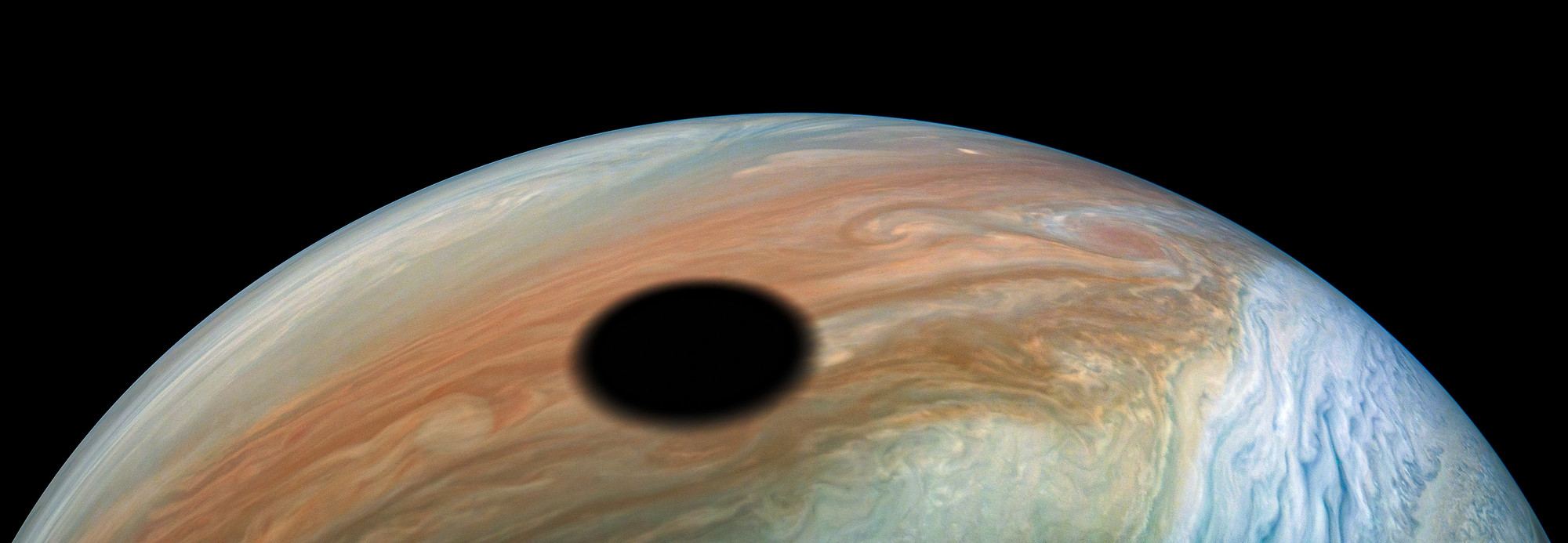

Continue reading “New Research Suggests Io Doesn’t Have a Shallow Ocean of Magma”Yes, This is Actually the Shadow of Io Passing Across the Surface of Jupiter.

The JunoCam onboard NASA’s Juno spacecraft continues to provide we Earthbound humans with a steady stream of stunning images of Jupiter. We can’t get enough of the gas giant’s hypnotic, other-worldly beauty. This image of Io passing over Jupiter is the latest one to awaken our sense of wonder.

This image was processed by Kevin Gill, a NASA software engineer who has produced other stunning images of Jupiter.

Continue reading “Yes, This is Actually the Shadow of Io Passing Across the Surface of Jupiter.”Io’s Largest Volcano, Loki, Erupts Every 500 Days. Any Day Now, It’ll Erupt Again.

Jupiter’s moon Io is in stark contrast to the other three Galilean moons. While Callisto, Ganymede, and Europa all appear to have subsurface oceans, Io is a volcanic world, covered with more than 400 active volcanoes. In fact, Io is the most volcanically active body in the Solar System.

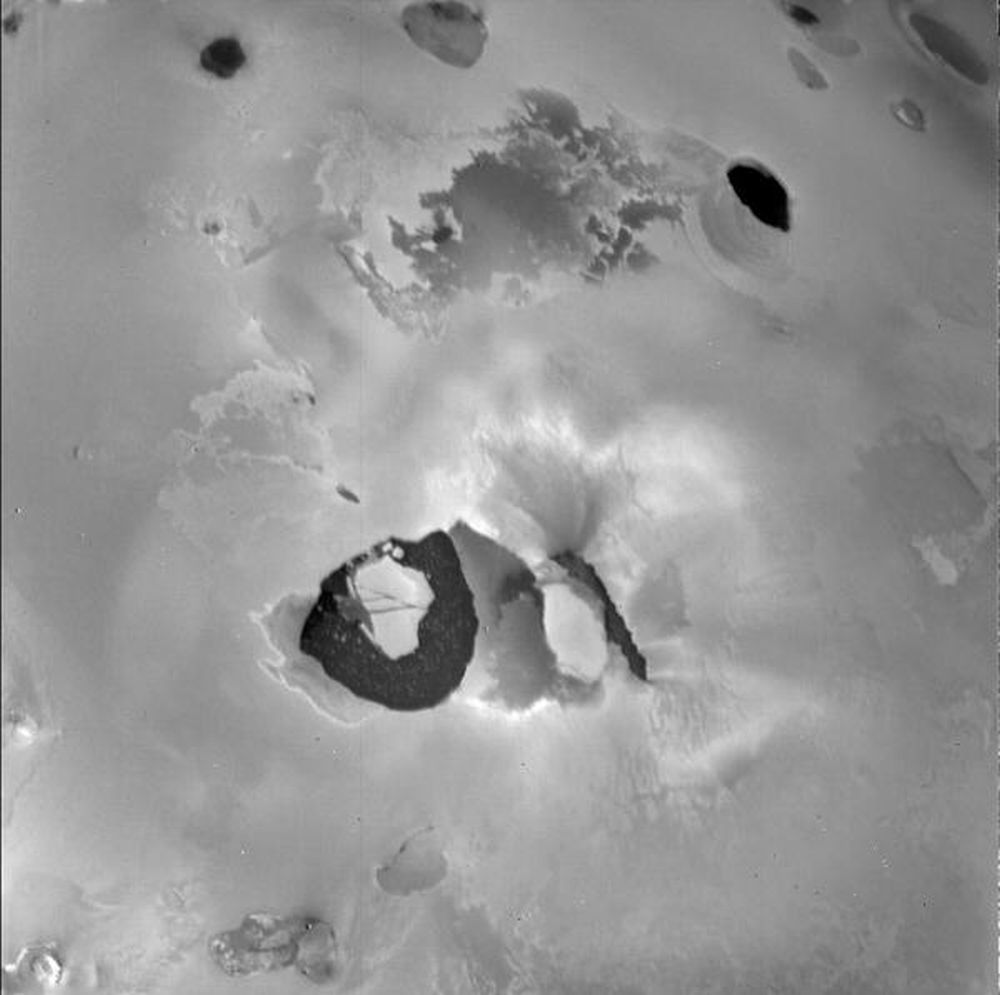

Io’s largest volcano is named Loki, after a God in Norse mythology. It’s the most active and most powerful volcano in the Solar System. Since 1979, we’ve known that it’s active and that it’s both continuous and variable. And since 2002, thanks to a research paper in the Geophysical Research Letters, we’ve known that it erupts regularly.

Continue reading “Io’s Largest Volcano, Loki, Erupts Every 500 Days. Any Day Now, It’ll Erupt Again.”Weekly Space Hangout: Mar 06, 2019 – Dr. Jeff Morgenthaler of the Planetary Science Institute

Hosts:

Dr. Morgan Rehnberg (MorganRehnberg.com / @MorganRehnberg & ChartYourWorld.org)

Dr. Kimberly Cartier (KimberlyCartier.org / @AstroKimCartier )

Dr. Pamela Gay (astronomycast.com / cosmoquest.org / @starstryder)

Jeff Morgenthaler, a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute, likes to think of himself as an experimental physicist whose laboratory opens to the sky. He has used a comet to measure the ionization lifetime of carbon, is using Io’s atmosphere as a probe of conditions in Jupiter’s magnetosphere and has constructed a small-aperture coronagraph to monitor measure Jupiter’s magnetospheric response to a large volcanic eruption on Io.

Being Cassini. Experience What It Was Like to Fly Past Jupiter and Saturn and Their Moons

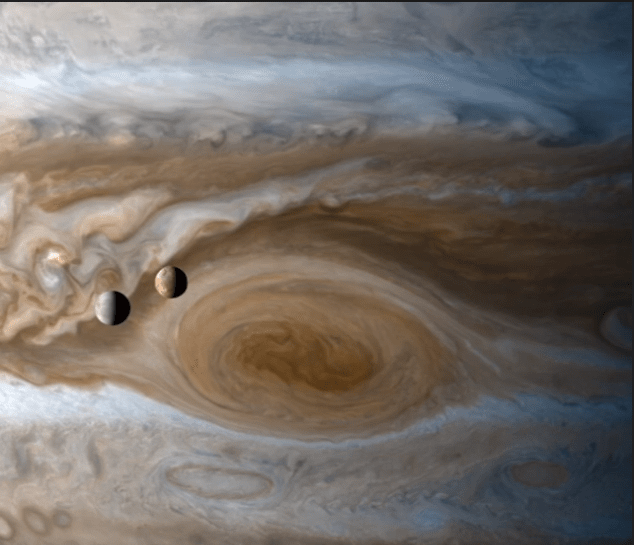

What would it be like to be onboard the Cassini orbiter as it made its way around Jupiter and Saturn and their moons? Pretty cool. Now a new video made from Cassini images pieces together parts of that stately journey.

NASA’s Juno Mission Spots Another Possible Volcano on Jupiter’s Moon Io

When the Juno spacecraft arrived in orbit around Jupiter in 2016, it became the second spacecraft in history to study Jupiter directly – the first being the Galileo probe, which orbited Jupiter between 1995 and 2003. With every passing orbit (known as a perijove, which take place every 53 days), the spacecraft has revealed more about Jupiter’s atmosphere, weather patterns, and magnetic environment.

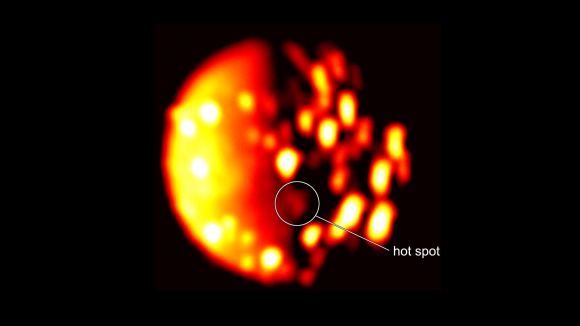

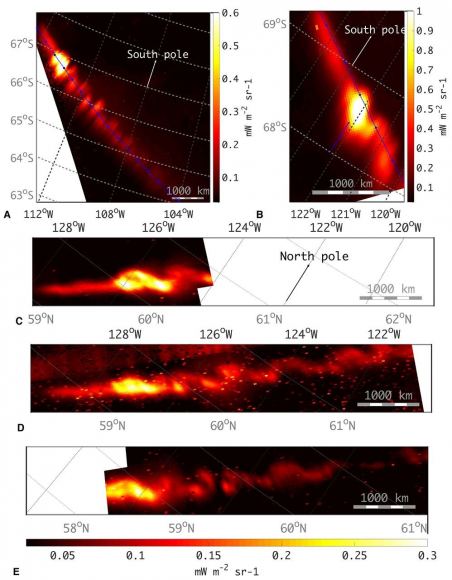

In addition, Juno recently discovered something interesting about Jupiter’s closest orbiting moon Io. Based on data collected by its Jovian InfraRed Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instrument, Juno detected a new heat source close to the south pole of Io that could indicate the presence of a previously undiscovered volcano. This is just the latest discovery made by the probe during its mission, which NASA recently extended to 2021.

The infrared data was collected on Dec. 16th, 2017, when the Juno spacecraft was about 470,000 km (290,000 mi) away from Io. As Alessandro Mura, a Juno co-investigator from the National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) in Rome, explained in a recent NASA press release:

“The new Io hotspot JIRAM picked up is about 200 miles (300 kilometers) from the nearest previously mapped hotspot. We are not ruling out movement or modification of a previously discovered hot spot, but it is difficult to imagine one could travel such a distance and still be considered the same feature.”

Aside from Juno and Galileo, many NASA missions have visited or passed through the Jovian System in the past few decades. These have including the Pioneer 10 and 11 missions in 1973/74, the Voyager 1 and 2 missions in 1979, and the Cassini and New Horizons missions in 2000 and 2007, respectively. Each of these missions managed to snap pictures of the Jovians moons on their way to the outer Solar System.

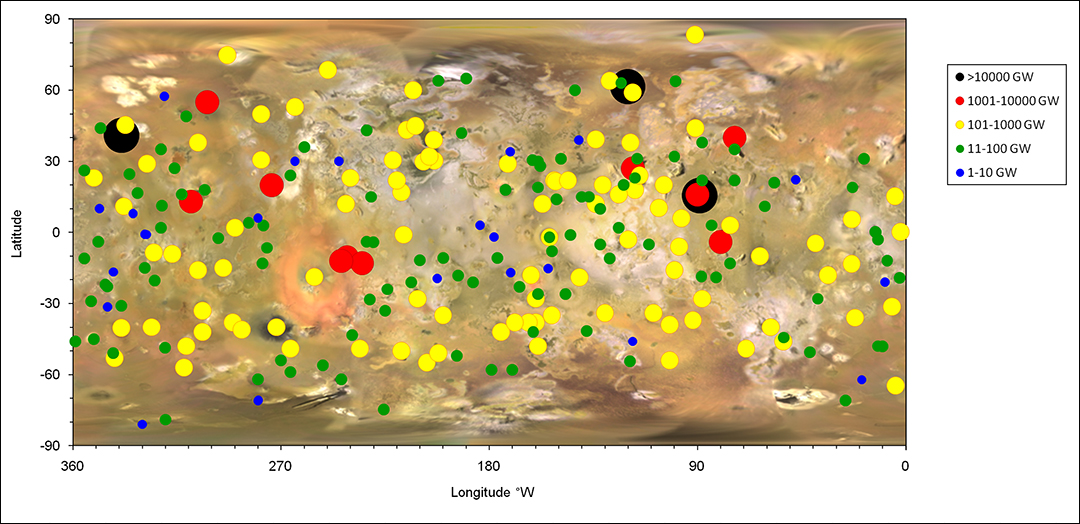

Combined with ground-based observations, scientists have accounted for over 150 volcanoes on the surface of Io so far, with estimates claiming there could over 400 in total. Since it entered Jupiter’s orbit on July 4th, 2016, the Juno probe has traveled nearly 235 million km (146 million mi) from one pole to other. On July 16th, Juno will conduct its 13th perijove maneuver, once again passing low over Jupiter’s cloud tops at a distance of about 3,400 km (2,100 mi).

During these flybys, Juno probes beneath the upper atmosphere to study the planet’s auroras to learn more about it’s structure, atmosphere and magnetosphere. By shedding light on these characteristics, the Juno probe will also teach us more about the planet’s origins and evolution. This in turn will teach scientists a great deal more about the formation and evolution of our Solar System, and perhaps how life began here.

Further Reading: NASA

Juno Data Shows that Some of Jupiter’s Moons are Leaving “Footprints” in its Aurorae

Since it arrived in orbit around Jupiter in July of 2016, the Juno mission has been sending back vital information about the gas giant’s atmosphere, magnetic field and weather patterns. With every passing orbit – known as perijoves, which take place every 53 days – the probe has revealed things about Jupiter that scientists will rely on to learn more about its formation and evolution.

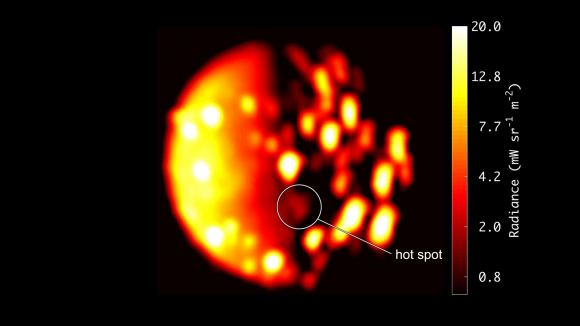

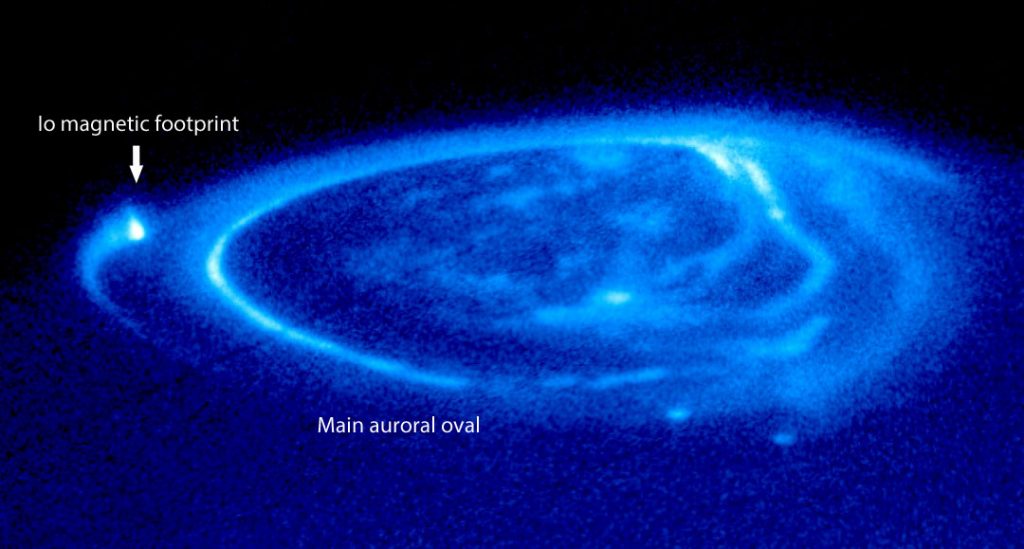

Interestingly, some of the most recent information to come from the mission involves how two of its moons affect one of Jupiter’s most interesting atmospheric phenomenon. As they revealed in a recent study, an international team of researchers discovered how Io and Ganymede leave “footprints” in the planet’s aurorae. These findings could help astronomers to better understand both the planet and its moons.

The study, titled “Juno observations of spot structures and a split tail in Io-induced aurorae on Jupiter“, recently appeared in the journal Science. The study was led by A. Mura of the International Institute of Astrophysics (INAF) and included members from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the Italian Space Agency (ASI), the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL), and multiple universities.

Much like aurorae here on Earth, Jupiter’s aurorae are produced in its upper atmosphere when high-energy electrons interact with the planet’s powerful magnetic field. However, as the Juno probe recently demonstrated using data gathered by Ultraviolet Spectrograph (UVS) and Jovian Energetic Particle Detector Instrument (JEDI), Jupiter’s magnetic field is significantly more powerful than anything we see on Earth.

In addition to reaching power levels 10 to 30 times greater than anything higher than what is experienced here on Earth (up to 400,000 electron volts), Jupiter’s norther and southern auroral storms also have oval-shaped disturbances that appear whenever Io and Ganymede pass close to the planet. As they explain in their study:

“A northern and a southern main auroral oval are visible, surrounded by small emission features associated with the Galilean moons. We present infrared observations, obtained with the Juno spacecraft, showing that in the case of Io, this emission exhibits a swirling pattern that is similar in appearance to a von Kármán vortex street.”

A Von Kármán vortex street, a concept in fluid dynamics, is basically a repeating pattern of swirling vortices caused by a disturbance. In this case, the team found evidence of a vortex streaming for hundreds of kilometers when Io passed close to the planet, but which then disappeared as the moon moved farther away from the planet.

The team also found two spots in the auroral belt created by Ganymede, where the extended tail from the main auroral spots eventually split in two. While the team was not sure what causes this split, they venture that it could be caused by interaction between Ganymede and Jupiter’s magnetic field (since Ganymede is the only Jovian moon to have its own magnetic field).

These features, they claim, suggest that magnetic interactions between Jupiter and Ganymede are more complex than previously thought. They also indicate that neither of the footprints were where they expected to find them, which suggests that models of the planet’s magnetic interactions with its moons may be in need of revision.

Studying Jupiter’s magnetic storms is one of the primary goals of the Juno mission, as is learning more about the planet’s interior structure and how it has evolved over time. In so doing, astronomers hope to learn more about how the Solar System came to be. NASA also recently extended the mission to 2021, giving it three more years to gather data on these mysteries.

And be sure to enjoy this video of the Juno mission, courtesy of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory:

Io Afire With Volcanoes Under Juno’s Gaze

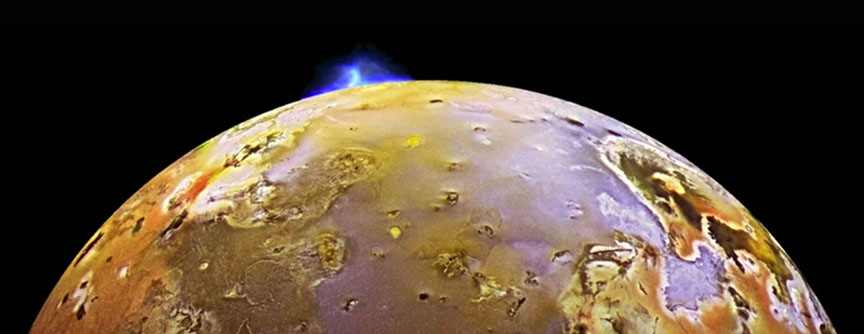

Volcanic activity on Io was discovered by Voyager 1 imaging scientist Linda Morabito. She spotted a little bump on Io’s limb while analyzing a Voyager image and thought at first it was an undiscovered moon. Moments later she realized that wasn’t possible — it would have been seen by earthbound telescopes long ago. Morabito and the Voyager team soon came to realize they were seeing a volcanic plume rising 190 miles (300 km) off the surface of Io. It was the first time in history that an active volcano had been detected beyond the Earth. For a wonderful account of the discovery, click here.

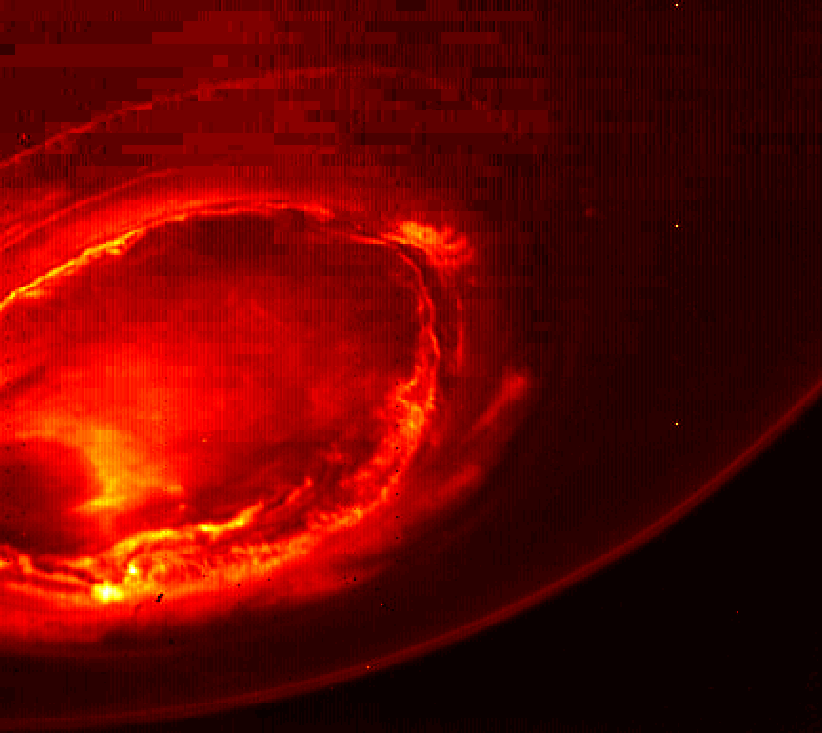

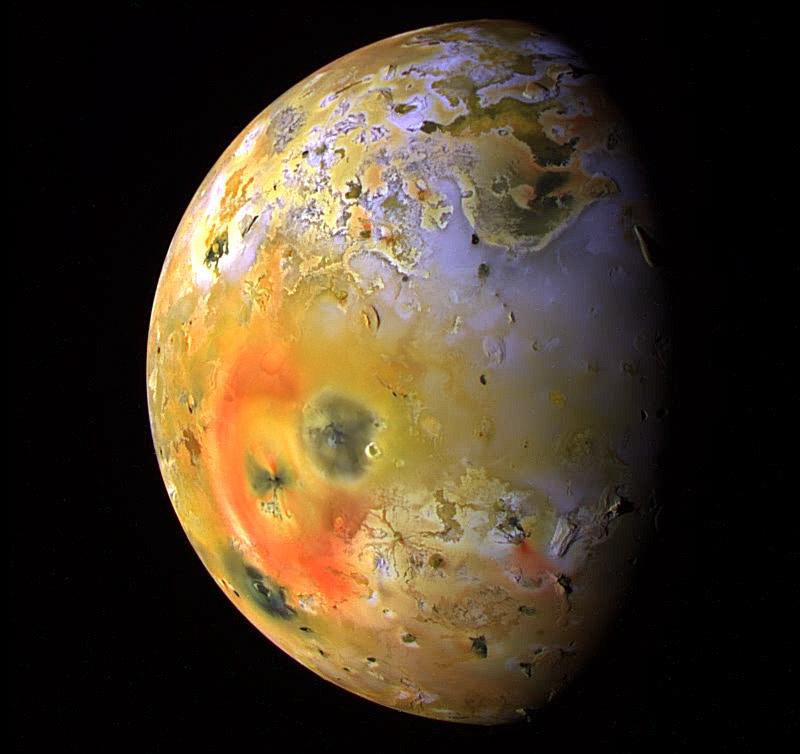

Today, we know that Io boasts more than 130 active volcanoes with an estimated 400 total, making it the most volcanically active place in the Solar System. Juno used its Jovian Infrared Aurora Mapper (JIRAM) to take spectacular photographs of Io during Perijove 7 last July, when we were all totally absorbed by close up images of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot.

Juno’s Io looks like it’s on fire. Because JIRAM sees in infrared, a form of light we sense as heat, it picked up the signatures of at least 60 hot spots on the little moon on both the sunlight side (right) and the shadowed half. Like all missions to the planets, Juno’s cameras take pictures in black and white through a variety of color filters. The filtered views are later combined later by computers on the ground to create color pictures. Our featured image of Io was created by amateur astronomer and image processor Roman Tkachenko, who stacked raw images from this data set to create the vibrant view.

Io’s hotter than heck with erupting volcano temperatures as high as 2,400° F (1,300° C). Most of its lavas are made of basalt, a common type of volcanic rock found on Earth, but some flows consist of sulfur and sulfur dioxide, which paints the scabby landscape in unique colors.

This five-frame sequence taken by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft on March 1, 2007 captures the giant plume from Io’s Tvashtar volcano.

Located more than 400 million miles from the Sun, how does a little orb only a hundred miles larger than our Moon get so hot? Europa and Ganymede are partly to blame. They tug on Io, causing it to revolve around Jupiter in an eccentric orbit that alternates between close and far. Jupiter’s powerful gravity tugs harder on the moon when its closest and less so when it’s farther away. The “tug and release”creates friction inside the satellite, heating and melting its interior. Io releases the pent up heat in the form of volcanoes, hot spots and massive lava flows.

Always expect big surprises from small things.

A Proposal For Juno To Observe The Volcanoes Of Io

Jupiter may be the largest planet in the Solar System with a diameter 11 times that of Earth, but it pales in comparison to its own magnetosphere. The planet’s magnetic domain extends sunward at least 3 million miles (5 million km) and on the back side all the way to Saturn for a total of 407 million miles or more than 400 times the size of the Sun.

If we had eyes adapted to see the Jovian magnetosphere at night, its teardrop-like shape would easily extend across several degrees of sky! No surprise then that Jove’s magnetic aura has been called one of the largest structures in the Solar System.

Io, Jupiter’s innermost of the planet’s four large moons, orbits deep within this giant bubble. Despite its small size — about 200 miles smaller than our own Moon — it doesn’t lack in superlatives. With an estimated 400 volcanoes, many of them still active, Io is the most volcanically active body in the Solar System. In the moon’s low gravity, volcanoes spew sulfur, sulfur dioxide gas and fragments of basaltic rock up to 310 miles (500 km) into space in beautiful, umbrella-shaped plumes.

Once aloft, electrons whipped around by Jupiter’s powerful magnetic field strike the neutral gases and ionize them (strips off their electrons). Ionized atoms and molecules (ions) are no longer neutral but possess a positive or negative electric charge. Astronomers refer to swarms of ionized atoms as plasma.

Jupiter rotates rapidly, spinning once every 9.8 hours, dragging the whole magnetosphere with it. As it spins past Io, those volcanic ions get caught up and dragged along for the ride, rotating around the planet in a ring called the Io plasma torus. You can picture it as a giant donut with Jupiter in the “hole” and the tasty, ~8,000-mile-thick ring centered on Io’s orbit.

That’s not all. Jupiter’s magnetic field also couples Io’s atmosphere to the planet’s polar regions, pumping Ionian ions through two “pipelines” to the magnetic poles and generating a powerful electric current known as the Io flux tube. Like firefighters on fire poles, the ions follow the planet’s magnetic field lines into the upper atmosphere, where they strike and excite atoms, spawning an ultraviolet-bright patch of aurora within the planet’s overall aurora. Astronomers call it Io’s magnetic footprint. The process works in reverse, too, spawning auroras in Io’s tenuous atmosphere.

Io is the main supplier of particles to Jupiter’s magnetosphere. Some of the same electrons stripped from sulfur and oxygen atoms during an earlier eruption return to strike atoms shot out by later blasts. Round and round they go in a great cycle of microscopic bombardment! The constant flow of high-speed, charged particles in Io’s vicinity make the region a lethal environment not only for humans but also for spacecraft electronics, the reason NASA’s Juno probe gets the heck outta there after each perijove or closest approach to Jupiter.

But there’s much to glean from those plasma streams. Astronomy PhD student Phillip Phipps and assistant professor of astronomy Paul Withers of Boston University have hatched a plan to use the Juno spacecraft to probe Io’s plasma torus to indirectly study the timing and flow of material from Io’s volcanoes into Jupiter’s magnetosphere. In a paper published on Jan. 25, they propose using changes in the radio signal sent by Juno as it passes through different regions of the torus to measure how much stuff is there and how its density changes over time.

The technique is called a radio occultation. Radio waves are a form of light just like white light. And like white light, they get bent or refracted when passing through a medium like air (or plasma in the case of Io). Blue light is slowed more and experiences the most bending; red light is slowed less and refracted least, the reason red fringes a rainbow’s outer edge and blue its inner. In radio occultations, refraction results in changes in frequency caused by variations in the density of plasma in Io’s torus.

The best spacecraft for the attempt is one with a polar orbit around Jupiter, where it cuts a clean cross-section through different parts of the torus during each orbit. Guess what? With its polar orbit, Juno’s the probe for the job! Its main mission is to map Jupiter’s gravitational and magnetic fields, so an occultation experiment jives well with mission goals. Previous missions have netted just two radio occultations of the torus, but Juno could potentially slam dunk 24.

Because the paper was intended to show that the method is a feasible one, it remains to be seen whether NASA will consider adding a little extra credit work to Juno’s homework. It seems a worthy and practical goal, one that will further enlighten our understanding of how volcanoes create aurorae in the bizarre electric and magnetic environment of the largest planet.