I’d like to think we’re smarter than the Sun.

Let’s compare and contrast. Humans, on the one hand, have made enormous advances in science and technology, built cities, cars, computers, and phones. We have split the atom for war and for energy.

What has the Sun done? It’s a massive ball of plasma, made up of mostly hydrogen and helium. It just, kind of, sits there. Every now and then it burps up hydrogen gas into a coronal mass ejection. It’s not a stretch to say that the Sun, and all inanimate material in the Universe, isn’t the sharpest knife in the drawer.

And yet, the Sun has mastered a form of energy that we just can’t seem to wrap our minds around: fusion. It’s really infuriating, seeing the Sun, just sitting there, effortlessly doing something our finest minds have struggled with for half a century.

Why can’t we make fusion work? How long until we can finally catch up technologically with a sphere of ionized gas?

The trick to the Sun’s ability to generate power through nuclear fusion, of course, comes from its enormous mass. The Sun contains 1.989 x 10^30 kilograms of mostly hydrogen and helium, and this mass pushes inward, creating a core heated to 15 million degrees C, with 150 times the density of water.

It’s at this core that the Sun does its work, mashing atoms of hydrogen into helium. This process of fusion is an exothermic reaction, which means that every time a new atom of helium is created, photons in the form of gamma radiation are also released.

The only thing the Sun uses this energy for is light pressure, to counteract the gravity pulling everything inward. Its photons slowly make their way up through the Sun and then they’re released into space. So wasteful.

How can we replicate this on Earth?

Now gathering together a Sun’s mass of hydrogen here on Earth is one option, but it’s really impractical. Where would we put all that hydrogen. The better solution will be to use our technology to simulate the conditions at the core of the Sun.

If we can make a fusion reactor where the temperatures and pressures are high enough for atoms of hydrogen to merge into helium, we can harness those sweet sweet photons of gamma radiation.

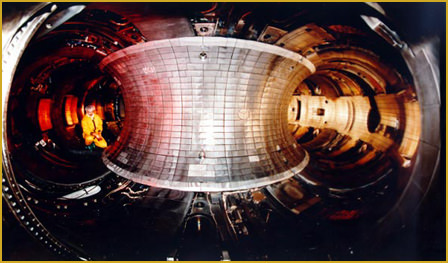

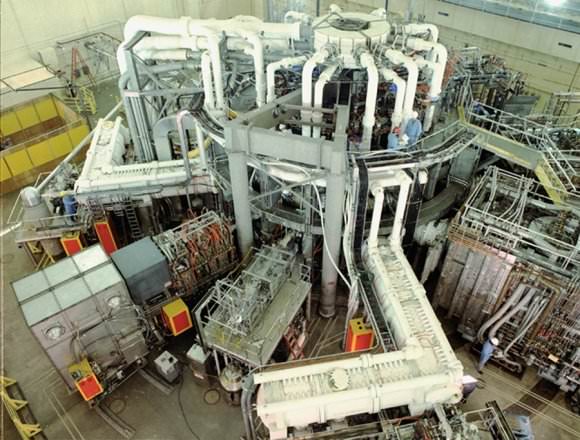

The main technology developed to do this is called a tokamak reactor; it’s a based on a Russian acronym for: “toroidal chamber with magnetic coils”, and the first prototypes were created in the 1960s. There are many different reactors in development, but the method is essentially the same.

A vacuum chamber is filled with hydrogen fuel. Then an enormous amount of electricity is run through the chamber, heating up the hydrogen into a plasma state. They might also use lasers and other methods to get the plasma up to 150 to 300 million degrees Celsius (10 to 20 times hotter than the Sun’s core).

Superconducting magnets surround the fusion chamber, containing the plasma and keeping it away from the chamber walls, which would melt otherwise.

Once the temperatures and pressures are high enough, atoms of hydrogen are crushed together into helium just like in the Sun. This releases photons which heat up the plasma, keeping the reaction going without any addition energy input.

Excess heat reaches the chamber walls, and can be extracted to do work.

The challenge has always been that heating up the chamber and constraining the plasma uses up more energy than gets produced in the reactor. We can make fusion work, we just haven’t been able to extract surplus energy from the system… yet.

Compared to other forms of energy production, fusion should be clean and safe. The fuel source is water, and the byproduct is helium (which the world is actually starting to run out of). If there’s a problem with the reactor, it would cool down and the fusion reaction would stop.

The high energy photons released in the fusion reaction will be a problem, however. They’ll stream into the surrounding fusion reactor and make the whole thing radioactive. The fusion chamber will be deadly for about 50 years, but its rapid half-life will make it as radioactive as coal ash after 500 years.

Now you know what fusion power is and how it works, what’s the current state, and how long until fusion plants give us unlimited cheap safe power, if ever?

Fusion experiments are measured by the amount of energy they produce compared to the amount of energy you put into them. For example, if a fusion plant required 100MW of electrical energy to produce 10 MW of output, it would have an energy ratio of 0.1. You want at least a ratio of 1. That means energy in equals energy out, and so far, no experiment has ever reached that ratio. But we’re close.

The Chinese are building the Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak, or EAST. In 2016, engineers reported that they had run the facility for 102 seconds, achieving temperatures of 50 million C. If true, this is an enormous advancement, and puts China ahead in the race to create stable fusion. That said, this hasn’t been independently verified, and they only published a single scientific paper on the milestone.

Researchers at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) in Germany recently announced that their Wendelstein 7-X (W7X) stellarator (I love that name), heated hydrogen gas to 80 million C for only a quarter of a second. Hot but short. A stellarator works differently than a tokamak. It uses twisted rings and external magnets to confine the plasma, so it’s good to know we have more options.

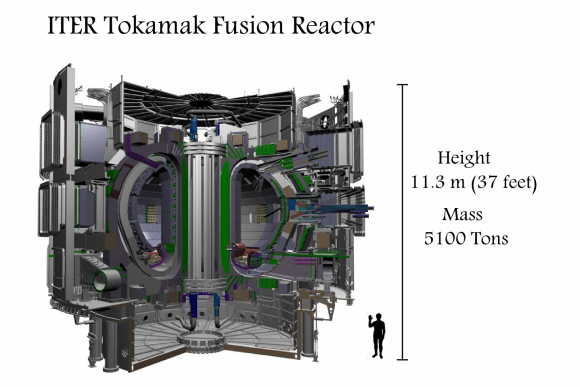

The biggest, most elaborate fusion experiment going on in the world right now is in Europe, at the French research center of Cadarache. It’s called ITER, which stands for the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, and it hopes to cross that magic ratio.

ITER is enormous, measuring 30 meters across and high. And its fusion chamber is so large that it should be able to create a self-sustaining fusion reaction. The energy released by the fusing hydrogen keeps the fuel hot enough to keep reacting. There will still be energy required to run the electric magnets that contain the plasma, but not to keep the plasma hot.

And if all goes well, ITER will have a ratio of 10. In other words, for every 10 MW of energy pumped in, it’ll generate 100 MW of usable power.

ITER is still under construction, and as of June 2015, the total construction costs had reached $14 billion. The facility is expected to be complete by 2021, and the first fusion tests will begin in 2025.

So, if ITER works as planned, we are now about 8 years away from positive energy output from fusion. Of course, ITER will just be an experiment, not an actual powerplant, so if it even works, an actual fusion-based energy grid will be decades after that.

At this point, I’d say we’re about a decade away from someone demonstrating that a self-sustaining fusion reaction that generates more power than it consumes is feasible. And then probably another 2 decades away from them supplying electricity to the power grid. By that point, our smug Sun will need to find a new job.