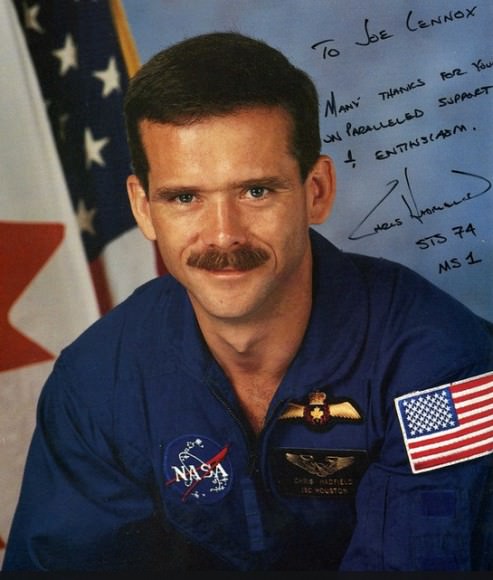

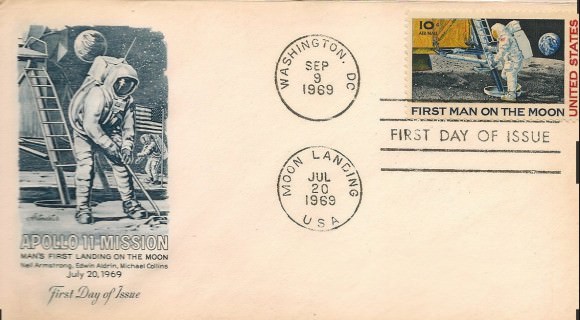

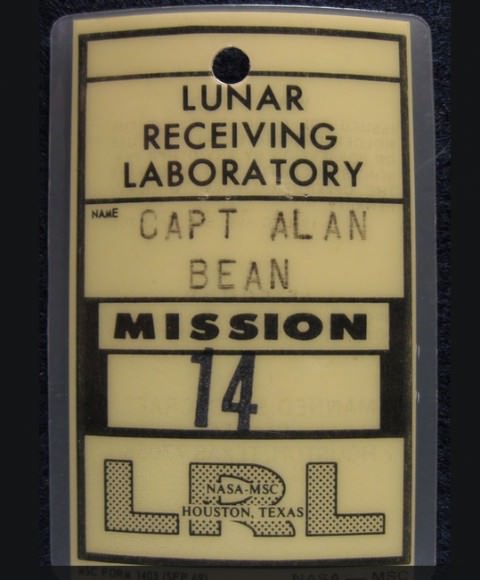

We’re all space geeks at Universe Today and are used to seeing collections of memorabilia, but there’s something about Joe Lennox’s that makes us set our phasers to stunned. Ever since John Glenn first rocketed to space 52 years ago, Lennox has been amassing a collection of newspaper articles, astronaut autographs, books and other memorabilia that he has on display in his New York City-area home.

As a child, he had to fight to save stuff with his sister; they eventually agreed to a “joint venture”, Lennox said. For 10 years, they clipped newspapers, wrote to NASA astronauts and space program employees (collecting their responses), and started branching out to movies and other things covering space exploration. Their mother allowed them to display the items in a back bedroom. Eventually, the interest of Lennox’s sister faded, but his only deepened.

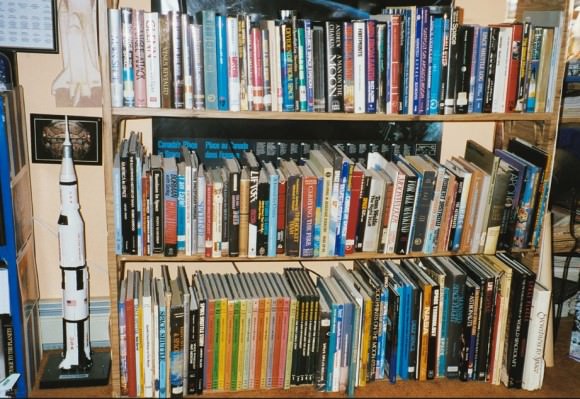

The collection has been through a few moves; his parents moved in 1978, meaning the stuff had to be stored wherever Lennox could find storage space until he and his wife bought their own house in 1990. There’s a spare bedroom available to display the collection, but the pictures indicate it’s simply bursting with items.

“My only problem is I don’t have enough room, because obviously as the years go by, I write (more) letters and purchase things,” Lennox told Universe Today.

Lennox makes sure to display his collection as carefully as he can. Scrapbook pages are acid-free, and letters are stored in acid-free folders as well. He says he has received space hardware (sometimes flown hardware) from contractors and others over the years, which he keeps in sealed display cases. Anything that remains outside of a sealed environment gets covered with a cloth when he’s not showing off the collection to house visitors.

It would be very difficult for a space fan to build such a collection today, he adds. NASA’s rules about “flown items” and other space memorabilia are tougher, with most items going to places such as the Smithsonian. Fewer people seem to answer his letters, too, Lennox said. “In the old days, if I wrote 100 letters, I would venture to say we got 95 really, really good responses. Today, if I wrote 100 letters I might get five responses. It’s very depressing, I got to tell you.”

With Lennox’s interest, a natural next question would be to ask if he ever considered working for NASA itself. While he never got that chance, the story ends up being a good one for the schoolkids he regularly speaks with.

Lennox said he never wanted to be an astronaut — “I’m not smart enough and don’t have the courage” — but he did have aspirations to be a flight controller. He said he began his university engineering studies with the idea for working for NASA, and happily worked away at his degree for a year and a half. Then he discovered he was going blind, requiring two corneal transplants.

The transplants worked, but it delayed his studies by four years and his eyesight was not as good as it used to be, meaning Lennox felt it was best to switch careers. He ended up in the banking industry, still writing letters to NASA and others the entire time. Now retired, he’s switching his energies over to teaching kids about space.

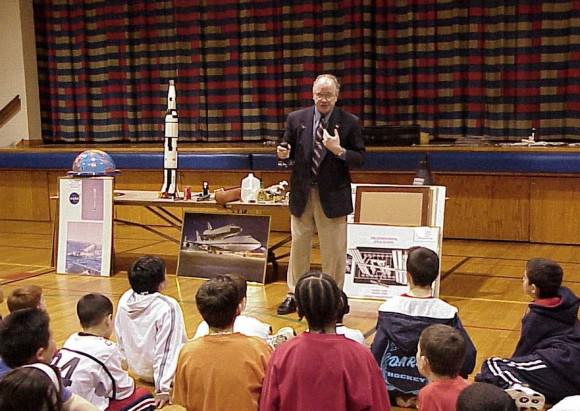

“I give presentations throughout New Jersey, 45 or 50 a year, where I go and I teach people about the space program,” he said. “I teach kids, I teach adults, I have probably 30 or 40 different presentations.”

His big message: “I want the children to understand they should never give up on their goals. If they have a goal in their life and it seems it can’t be reached because of health, like me, or money or relocation or whatever, they still can do it.”

You can see more pictures of Lennox’s “museum” below or at his website. He said he has willed the collection to an Orlando-area museum upon his death, meaning it could be viewable by the public in generations to come.