Back in 2007, when the Constellation program to return to the Moon was still the program of record for NASA, a group from Lockheed Martin began investigating how they might be able to use the Orion lunar capsule to send humans on a mission to an asteroid. Originally, this plan — called Plymouth Rock — was just a study to see how an asteroid mission with Orion could possibly serve as a complement to the baseline of Constellation’s lunar mission plans.

Now, it has turned into much more.

Thanks to John O’Connor from NASATech.net, we are able to show you some views of the Orion MPCV inside Lockheed Martin’s facilities in Boulder, Colorado. If you click on the images, you’ll be taken to the NASATech website and extremely large versions of the images that you can pan around and see incredible details of the MPCV and the building.

After canceling Constellation in February of 2010, two months later President Obama outlined sending astronauts to a nearby asteroid by 2025 and going to Mars by the mid-2030’s.

In May of 2011, NASA confirmed that the centerpiece of those missions will be the Orion – now called the Orion MultiPurpose Crew Vehicle. The repurposed Orion lunar vehicle would now be going to an asteroid, just like Josh Hopkins and his team from Lockheed Martin envisioned in their Plymouth Rock study.

Hopkins is the Principal Investigator for Advanced Human Exploration Missions, a team of engineers who develop plans and concepts for a variety of future human exploration missions.

“Normally when you take a spacecraft or a piece of hardware that has been designed for one job and you try to figure out how to use it for a different job, you discover there are all these details that don’t work out quite right,” Hopkins told Universe Today. “But we were pleasantly surprised that when we took this lunar version of Orion and applied it to an asteroid mission, it is a really flexible and capable vehicle and a lot of the requirements for the lunar mission match pretty well with the asteroid mission.”

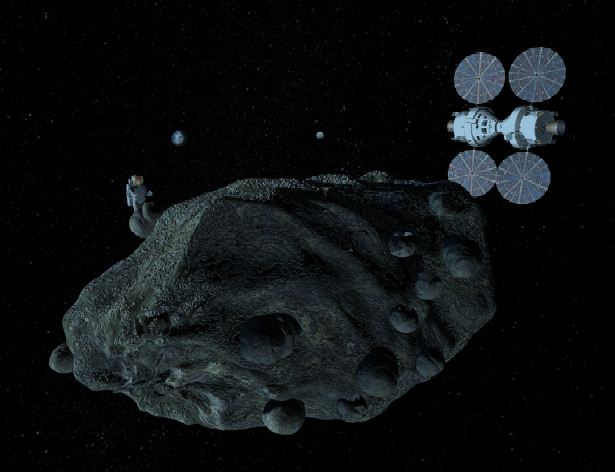

The Plymouth Rock design called for using two specially modified Orion spacecraft docked nose to nose in order to provide enough living space, propulsion, and life-support for two astronauts heading to an asteroid. But NASA has said the MPCV will be used primarily for launch and entry while a larger habitation module would be docked to the MPCV to enable a crew of 4 to travel to deep space.

Shuttle astronaut Tom Jones was impressed with the Plymouth Rock concept, but knows a larger companion vehicle will be needed for a trip to an asteroid. “Plymouth Rock is the minimalist approach to do an asteroid mission,” he said. “That’s one way to solve the redundancy problem in the short-term.”

But even developing an in-space habitat could be a matter of repackaging things we already have. “The hab module could be derived directly from what we’ve done for space station, or it could be a commercial inflatable like from Bigelow, so that might be tried out by a commercial station or hotel in the next 10 years, so that would be demonstrated technology,” Jones said.

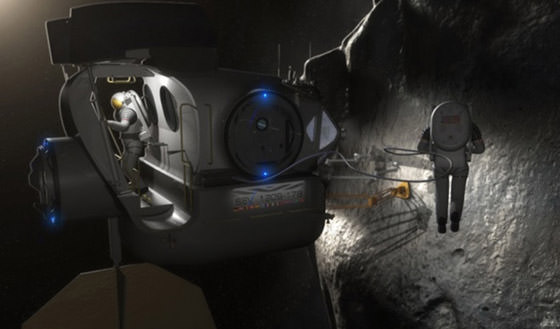

“Basically the tradeoff between a larger in-space habitat module versus the dual Orion approach is that by having a separate habitat you have more living space, more storage space, and there is the potential that it would be better for performing spacewalks,” said Hopkins. “But then you have to invest the costs for developing that system.”

Hopkins added that when he and his team initially conceived the Plymouth Rock mission, they were trying to figure out how to do an asteroid mission for as little as possible. Using two Orions was cheaper than developing a module specific to an asteroid mission.

“For Plymouth Rock, we had spelled out the need to basically increase the amount of food, water, oxygen and storage in the spacecraft, and some of that is accomplished by the fact of having two spacecraft,” Hopkins said.

For now, NASA hasn’t yet changed many of the requirements for the MPCV from what they previously were for the lunar vehicle, and as the mission design evolves, so might the MPCV. But so far, the lunar design seems to be working, and Hopkins said there are several design features already in Orion that make it very capable as a deep space vehicle.

For lunar missions, Orion was designed for basically 21 days with a crew on board going from Earth to the Moon and back and having a roughly have a six month “loiter period” while the crew was down on the lunar surface. That scenario would work for an asteroid mission, as a crewed flight to an asteroid would likely be about a six-month roundtrip journey, depending on the destination.

“So in things like reliability, leak rate of atmosphere in the cabin, and protection from radiation and micrometeorites, Orion is already designed for 6-7 month missions for the hardware,” Hopkins explained. “It is just not designed to have people for that long of time period.”

Orion has solar arrays rather than fuel cells like Apollo, which enable longer missions. Another big selling point is that the MPCV is designed to be 10 times safer during ascent and entry than its predecessor, the space shuttle.

“The reentry speeds are just a little bit faster for an asteroid mission than a lunar mission,” Hopkins said, “but current the thermal protection system we have should be able to handle it.”

Inside the MPCV is 9 cubic meters of habitable volume. “That is not total pressurized volume of the structure, but the space that’s left after computers, seats, supplies are all accounted for,” said Hopkins. “That’s about twice the size of a modern passenger van, like a Toyota Sienna.”

One big challenge is to figure out how use every nook and cranny to package a lot of supplies in a small amount of space, as the Orion could serve as a storeroom of sorts. “We think it’s possible,” Hopkins said. “We’ve done initial calculations that we can pack a reasonable amount of volume but it would be a pretty tight fit and we also have to think about the secondary things that need to be included, so that’s work that is ongoing.”

Logistically, the Orion MPCV could even support doing an EVA from the hatch on the capsule.

“We have a hatch that is big enough that an astronaut in a space suit can get out,” Hopkins said, “and the internal systems in the spacecraft are designed to tolerate the cabin being depressurized. We don’t rely on air circulation to carry the heat away from the electronics – they have their own cold plates to take the heat away. The knobs are designed to be manipulated with spacesuit gloves on, not just bare hands. A lot of those features just worked out to be pretty applicable to the asteroid mission because it was designed for a similar set of mission requirements.”

Hopkins knows the requirements and capabilities the Orion, as well as the in-space habitat will likely change over time, depending on the destination and the timeline. “If the plan is to go to the moons of mars or distant asteroids relatively soon, say in the late 2020’s or early 2030s, you might go ahead and build a relatively large, capable in space habitat, because you will definitely need it for those more distant missions. But if the idea were to go to the easiest asteroids to get to and do that relatively soon, then you might stick with a smaller simpler habitat module, or perhaps even the twin Orion approach.”

When the MPCV does return from a mission to an asteroid, it will likely land in the Pacific Ocean. NASA has begun some at NASA’s Langley Research Center to certify the vehicle for water landings. Engineers have dropped a 22,000-pound MPCV mockup into the basin. The test item is similar in size and shape to MPCV, but is more rigid so it can withstand multiple drops. Each test has a different drop velocity to represent the MPCV’s possible entry conditions during water landings.

So while these tests are happening and while Hopkins and his team from Lockheed Martin are working on and testing the Orion MPCV, NASA is still trying to decide on a heavy-lift launch system capable of bringing humans beyond low Earth orbit and they have not named anyone to lead the design of a human mission to an asteroid. The NASA website doesn’t even have any official information about a human asteroid mission; it only mentions “beyond low Earth orbit” as the next stop for humans.

“We’re talking about something that is going to happen in 2025 so we haven’t even decided on a spacecraft yet,” said Michael Braukus from NASA’s Exploration Systems Mission Directorate via a phone call. “We’re planning on the asteroid mission happening; it’s just that we haven’t designated a person to be responsible for the asteroid mission itself. We have the Orion MPCV under construction and we are awaiting on the decision of a space launch system, which will be the rocket that will carry it to deep space, and we’re progressing down the road, but haven’t reached a point yet where we have actually assigned someone to start developing the mission.”

So, that appears to be NASA’s current biggest hurdle to a human asteroid mission: deciding on the Space Launch System.

Previous article in this series: Human Mission to an Asteroid: Why Should NASA Go?

You can follow Universe Today senior editor Nancy Atkinson on Twitter: @Nancy_A. Follow Universe Today for the latest space and astronomy news on Twitter @universetoday and on Facebook.