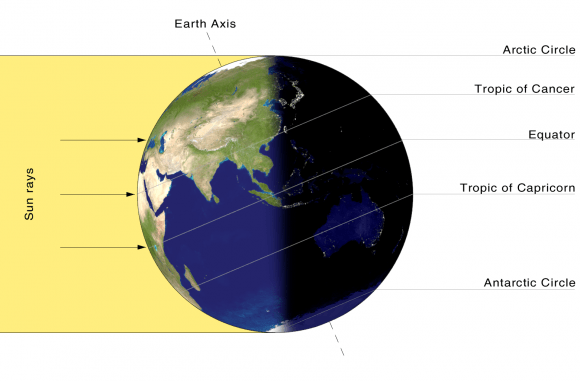

Can you feel the heat? If you find yourself north of the equator, astronomical summer kicks off today with the arrival of the summer solstice. In the southern hemisphere, the reverse is true, as today’s solstice marks the start of winter.

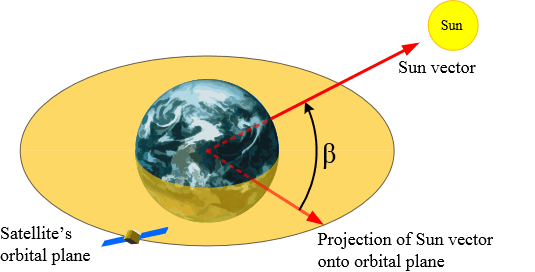

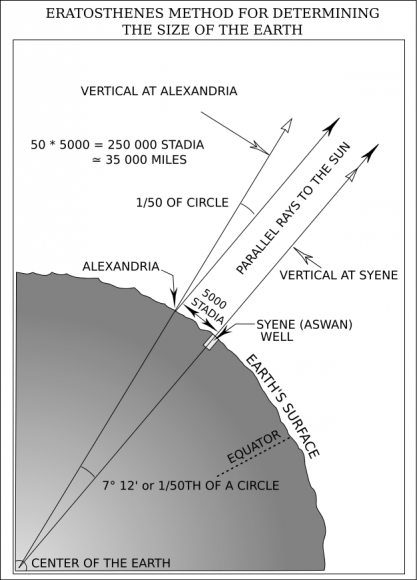

Thank our wacky seasons, and the 23.4 degree tilt of the Earth’s axis for the variation in insolation. Today, all along the Tropic of Cancer at latitude 23.4 degrees north, folks will experience what’s known as Lahiana Noon, as the Sun passes through the zenith directly overhead. Eratosthenes first noted this phenomena in 3rd century BC from an account in the town of Syene (modern day Aswan), 925 kilometers to the south of Alexandria, Egypt. The account mentioned how, at noon on the day of the solstice, the Sun shined straight down a local well, and cast no shadows. He went on to correctly deduce that the differing shadow angles between the two locales is due to the curvature of the Earth, and went on to calculate the curvature of the planet for good measure. Not a bad bit of reasoning, for an experiment that you can do today.

And although we call it the Tropic of Cancer, and the astrological sign of the Crab begins today as the Sun passes 90 degrees longitude along the ecliptic plane as seen from Earth, the Sun now actually sits in the astronomical constellation of Taurus on the June northward solstice. Thank precession; live out a normal 72 year human life span, and the solstice will move one degree along the ecliptic—stick around about 26,000 years, and it will complete one circuit of the zodiac. That’s something that your astrologer won’t tell you.

The solstice in the early 21st century actually falls on June 20th, thanks to the ‘reset’ the Gregorian calendar received in 2000 from the addition of a century year leap day. The actual moment the Sun reaches its northernmost declination today and slowly reverses its apparent motion is 22:34 Universal Time (UT). In 2016, the Moon reaches Full just 11 hours to the solstice. The last time a Full Moon fell within 24 hours of a solstice was December 2010, and we had a total lunar eclipse to boot. Such a coincidence won’t occur again until December 2018. You get a good study in celestial mechanics 101 tonight, as the Full Moon rises opposite to the setting Sun. The Moon occupies the southern region of the sky where the Sun will reside this December during the other solstice, when the Full Moon will then ride high in the night sky, and gets ever higher as we head towards a Major Lunar Standstill in 2025.

Of course, this motion of the Sun through the year is all an illusion from our terrestrial biased viewpoint. We’re actually racing around the Sun to the tune of 30 kilometers per second. You wouldn’t know it as summer heats up in the northern hemisphere, but we’re headed towards aphelion or the farthest point from the Sun for the Earth on July 4th at 152 million kilometers or 1.017 astronomical units (AU) distant. And the latest sunset as seen from latitude 40 degrees actually occurs on June 27th at 7:33 PM (not accounting for Daylight Saving Time) go much further north (like the Canadian Maritimes or the UK) and true astronomical darkness never occurs in late June.

And speaking of the Sun, we’re wrapping up the end of the 11 year solar cycle this year… and there are hints that we may be in for another profound solar minimum similar to 2009. We’ve already had a brief spotless stretch last month, and some solar astronomers have predicted that solar cycle #25 may be absent all together. This means a subsidence in aurorae, and an uncharacteristically blank Sol.

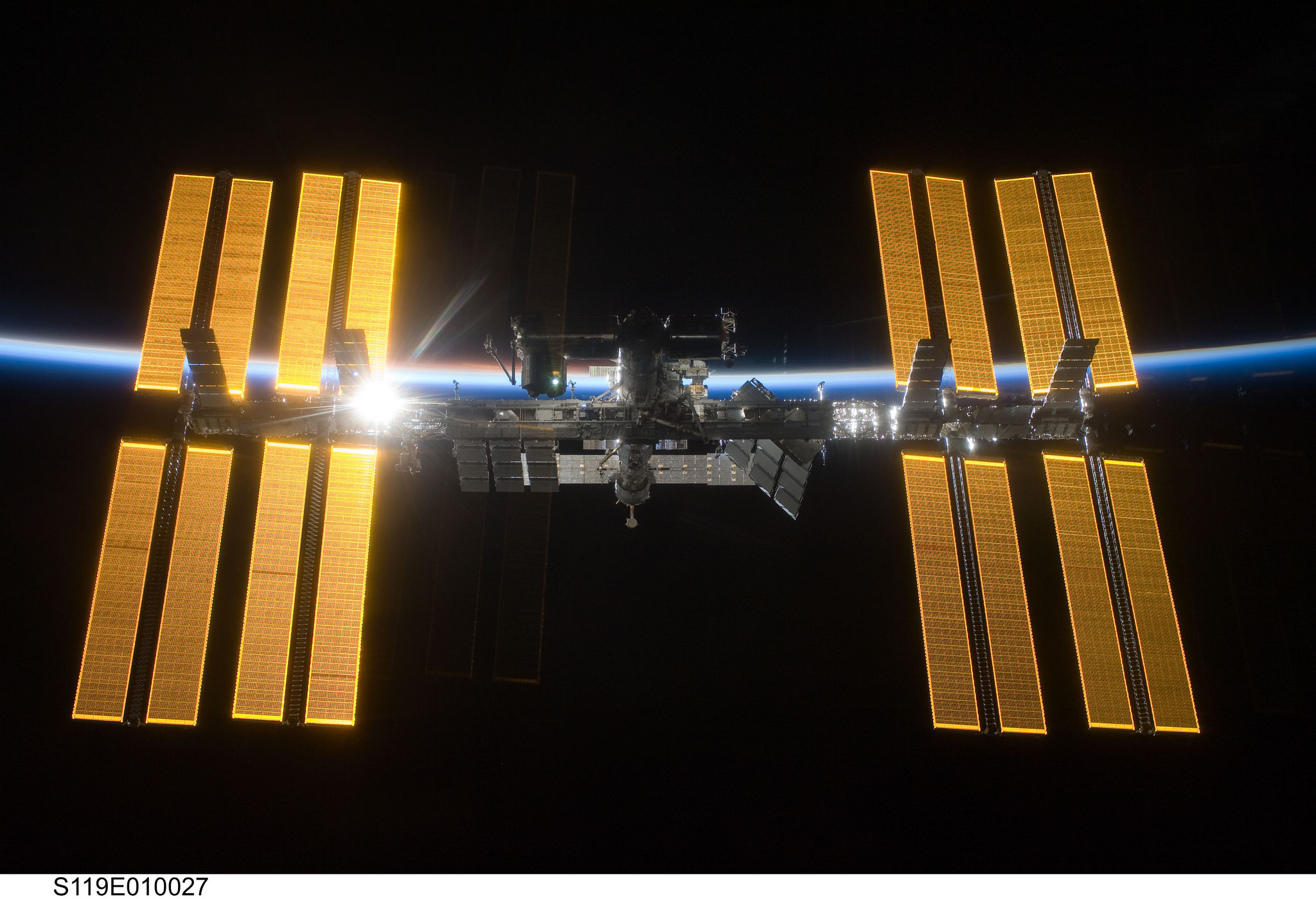

But don’t despair and pack it in for the summer. As a consolation prize, high northern latitudes have in recent years played host to electric blue noctilucent clouds near the June solstice. Also, the International Space Station enters a second period of full illumination through the entire length of its orbit from July 26th to 28th, making for the possibility of seeing multiple passes in a single night.

And folks in the Islamic world (and travelers such as ourselves currently in Morocco) can rejoice, as the Full Moon means that we’re half way through the fasting lunar month Ramadan. This is an especially tough one, as Ramadan 2016 goes right through the summer solstice, making for only a brief six hour span to break the fast each night and prepare for another 18 hour long stretch… and to repeat this pattern for 29 days straight. It’s a fascinating time of night markets and celebration, but for travelers, it also means odd opening hours and delays.

See any curious solstice shadow alignments in your neighborhood today?

Happy Lahiana Noon… from here on out, northern viewers slowly start to take back the night!