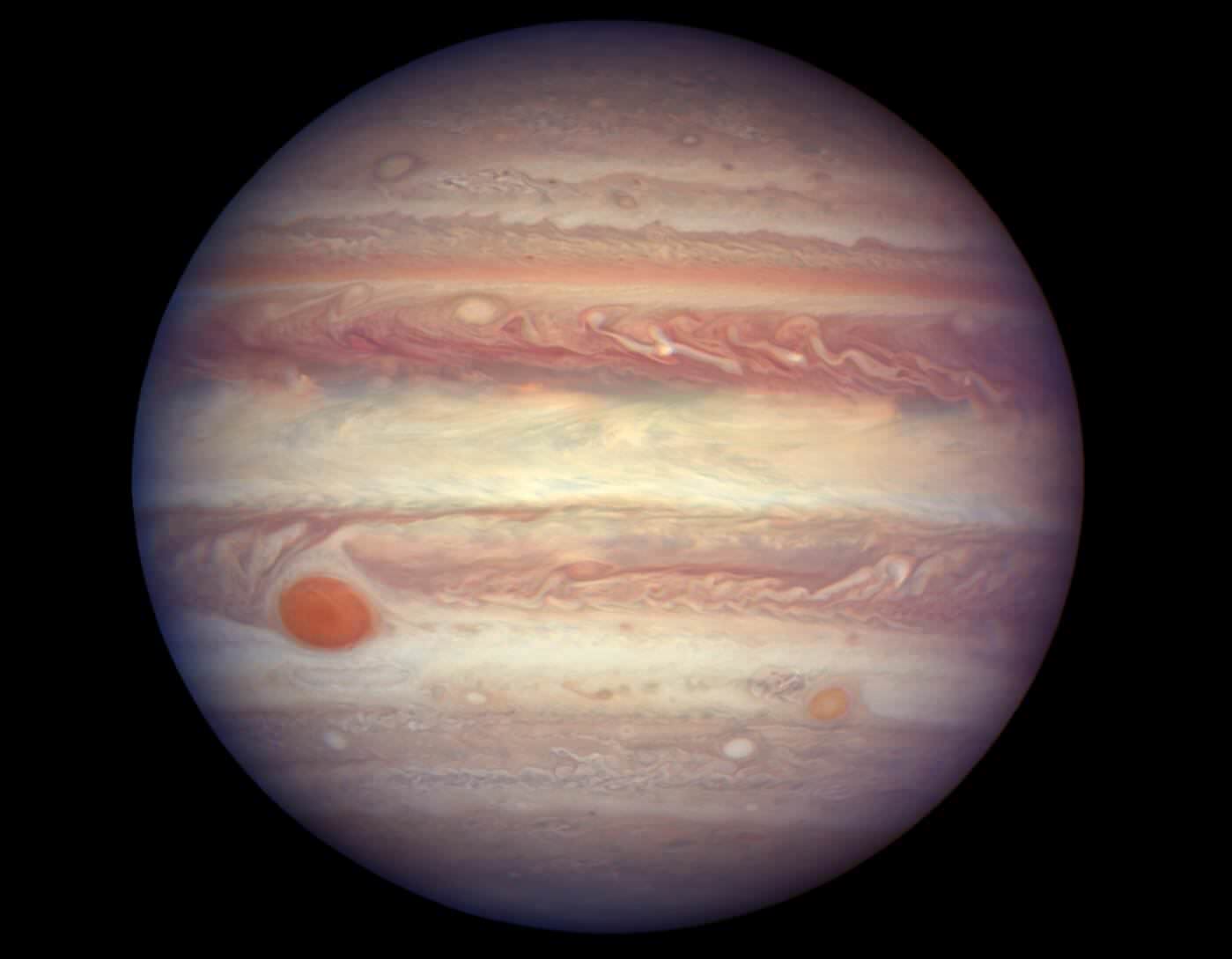

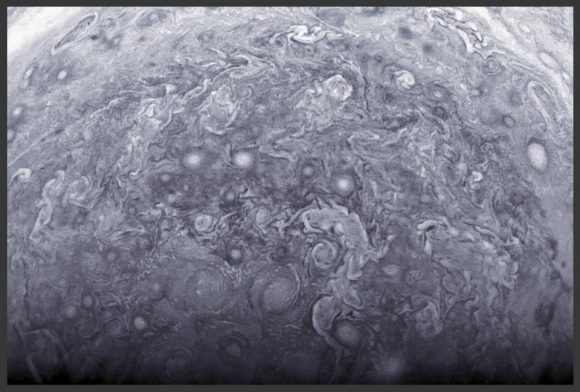

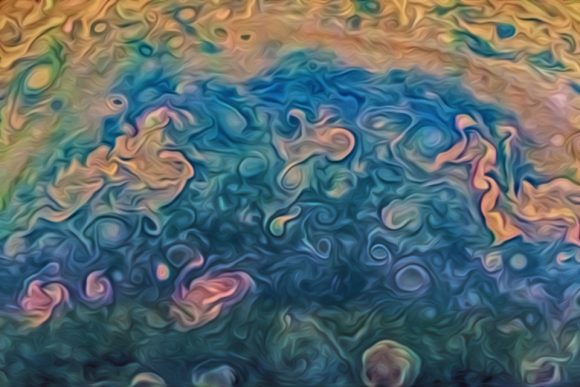

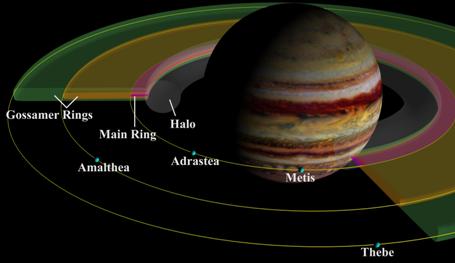

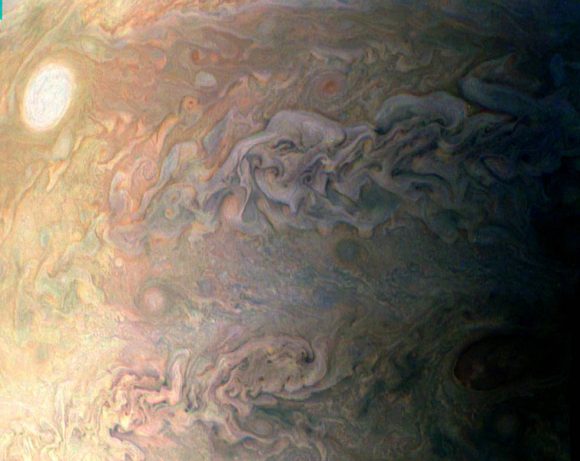

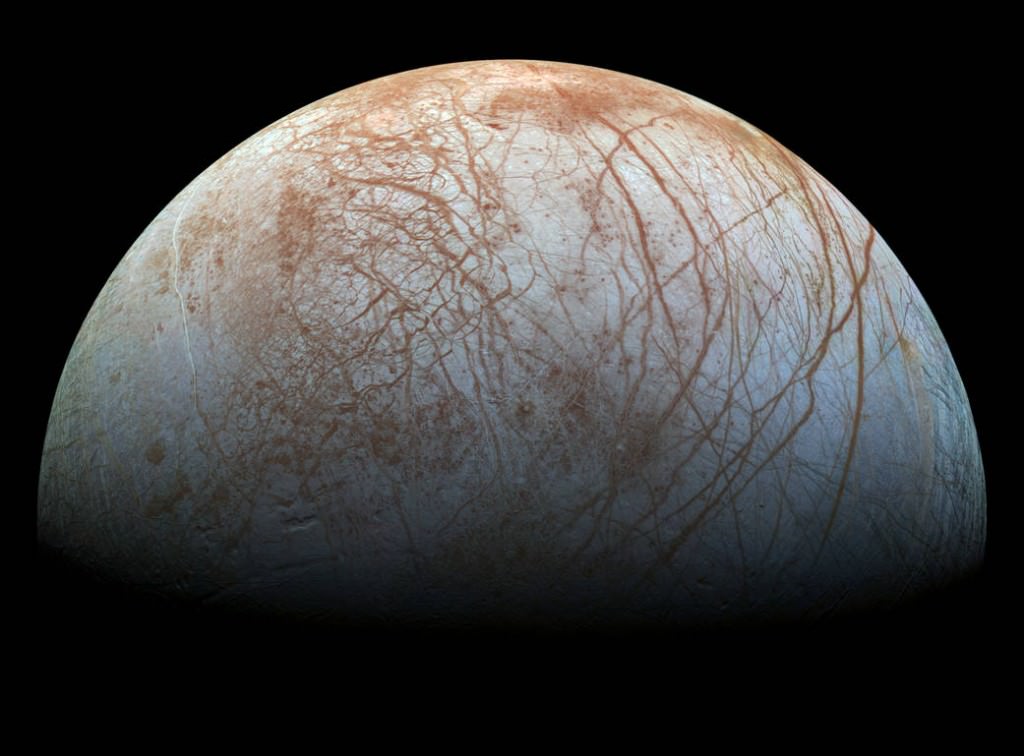

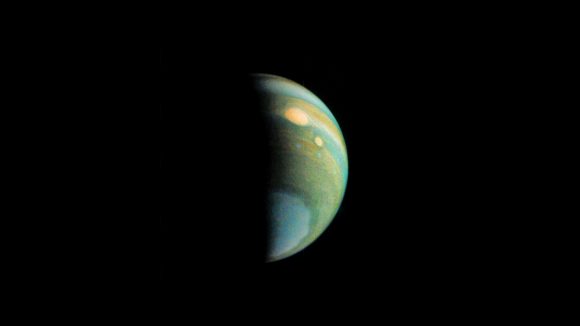

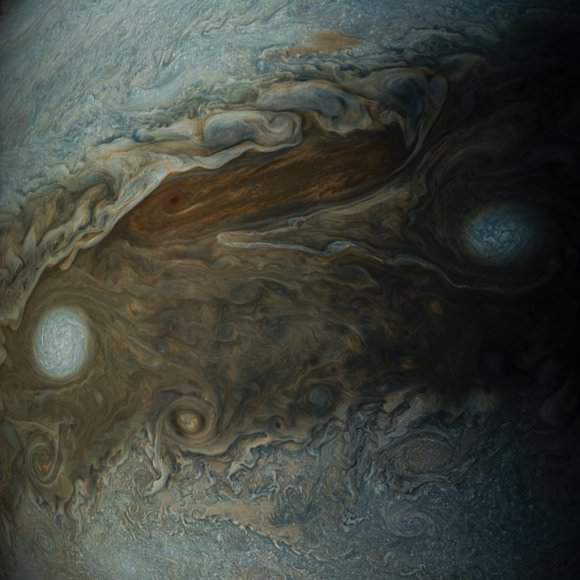

Even a casual observer can see how complex Jupiter might be. Its Great Red Spot is one of the most iconic objects in our Solar System. The Great Red Spot, which is a continuous storm 2 or 3 times as large as Earth, along with Jupiter’s easily-seen storm cloud belts, are visual clues that Jupiter is a complex place.

We’ve been observing the Great Red Spot for almost 200 years, so we’ve known for a long time that something special is happening at Jupiter. Now that the Juno probe is there, we’re finding that Jupiter might be a more surprising place than we thought.

“There is so much going on here that we didn’t expect that we have had to take a step back and begin to rethink of this as a whole new Jupiter.” – Scott Bolton, Juno’s Principal Investigator at the Southwest Research Institute.

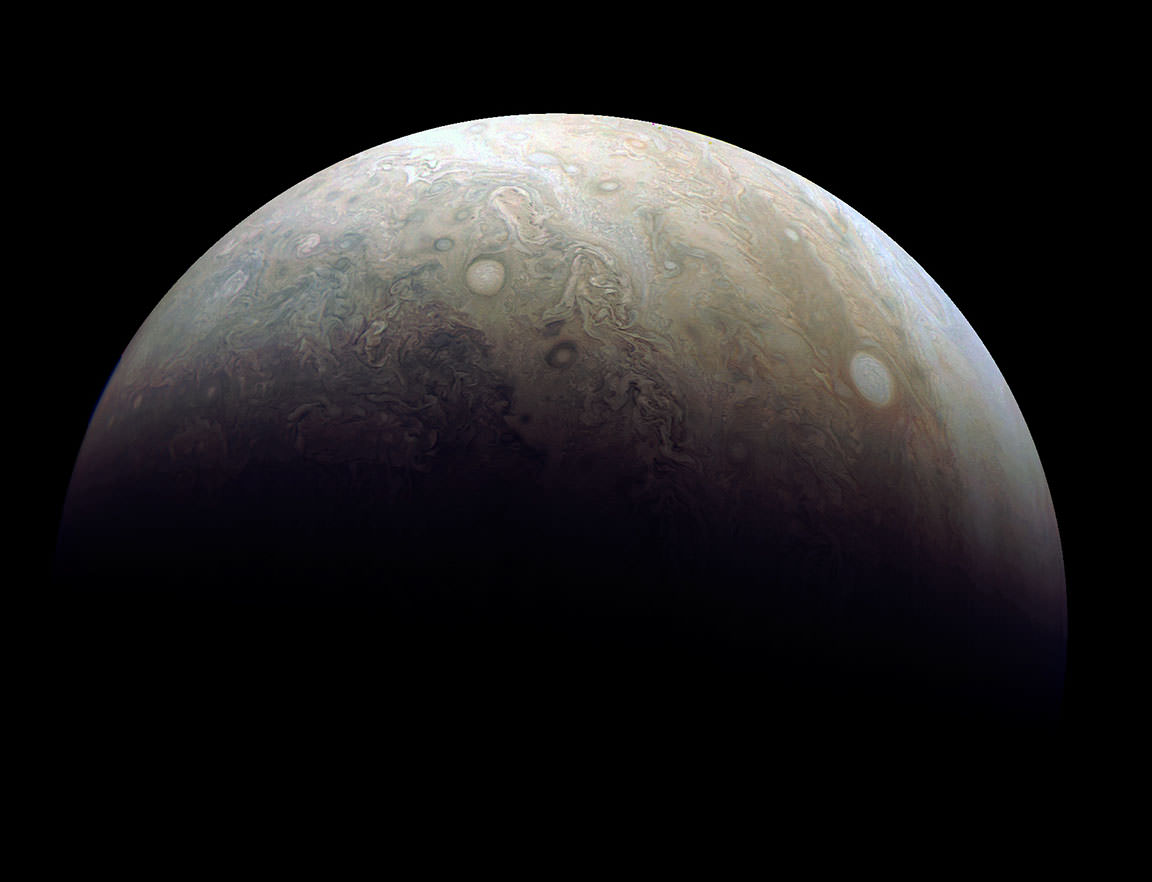

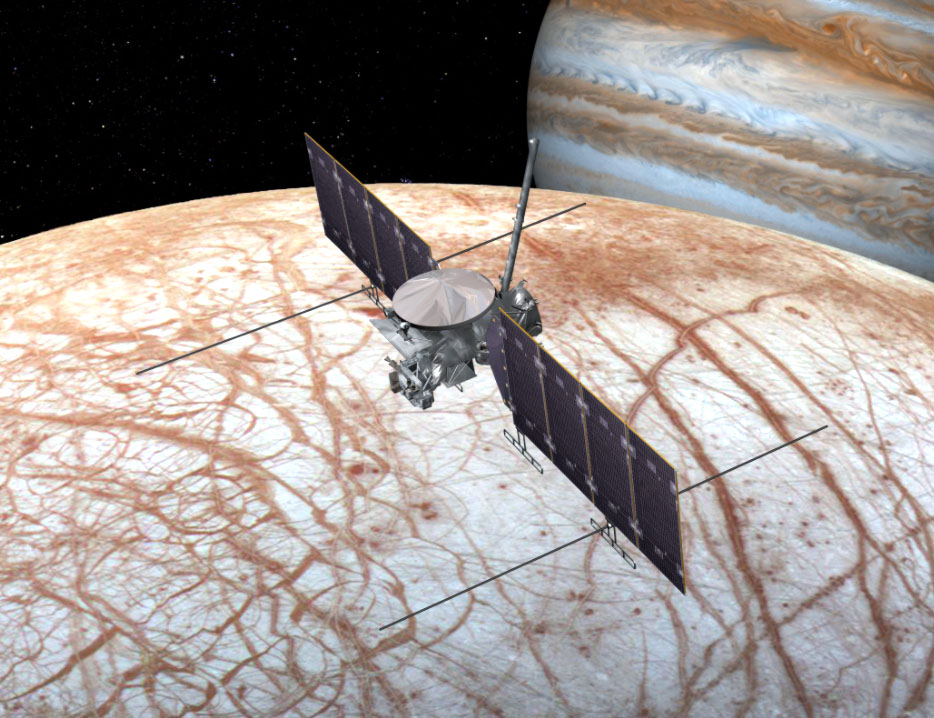

So far, the stunning images delivered to us by the JunoCam have stolen the show. But Juno is a science mission, and the fantastic images we’re feasting on might stir the imagination, but it’s the science that’s at the heart of the mission.

The Juno probe arrived at Jupiter in July 2016, and completed its first data-pass on August 27th, 2016. That pass took it to within 4,200 km of Jupiter’s cloud tops. Results from that first pass are being published in the journal Science and in Geophysical Research Letters.

Taken together, the results confirm what we might have guessed by just looking at Jupiter from afar: it is a stormy, complex, turbulent world.

“It was a long trip to get to Jupiter, but these first results already demonstrate it was well worth the journey.” – Diane Brown, Juno Program Executive.

“We are excited to share these early discoveries, which help us better understand what makes Jupiter so fascinating,” said Diane Brown, Juno program executive at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “It was a long trip to get to Jupiter, but these first results already demonstrate it was well worth the journey.”

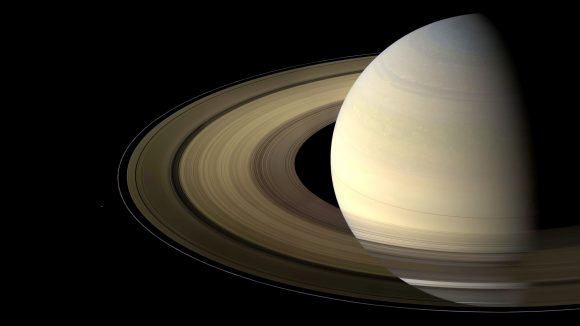

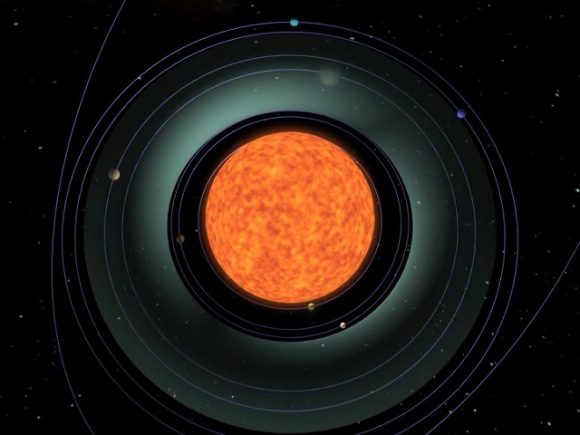

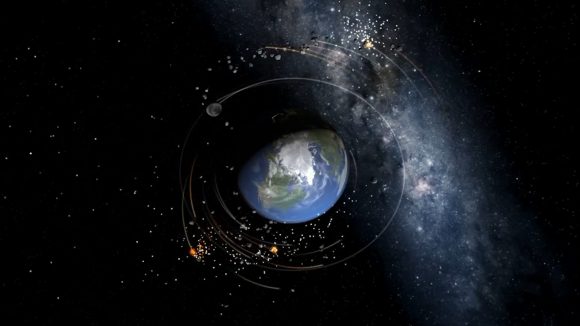

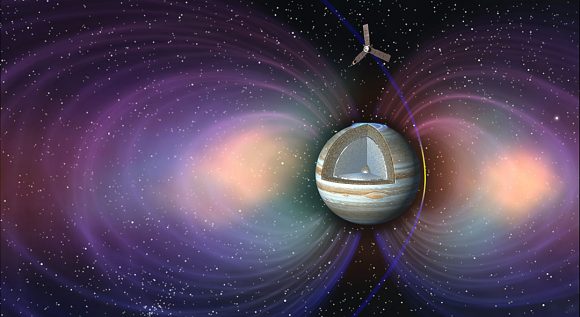

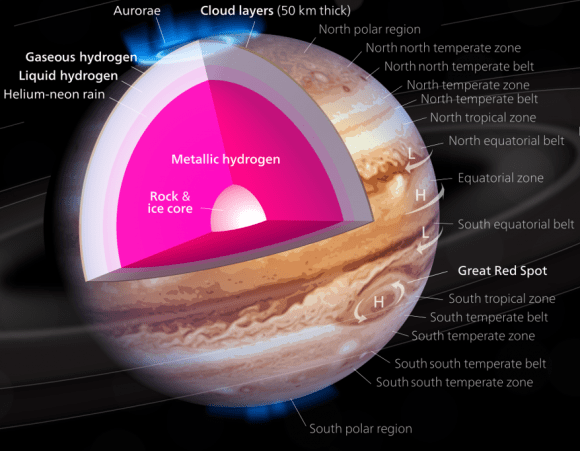

Jupiter’s Magnetic Field

We’ve known for a long time that Jupiter has the most powerful magnetic field in the Solar System. In fact, the magnetic field is what shaped the design of the Juno probe, and the profile of the mission itself. Juno’s Magnetometer Investigation (MAG) has measured the gas giant’s magnetosphere up close, and these measurements tell us that the magnetic field is even stronger than anticipated, and its shape is more irregular as well. At 7.66 Gauss, the field is about 10 times more powerful than Earth.

The irregularities in the magnetic field are an indication that the field is generated closer to the surface than thought. Earth generates its magnetic field from it its rotating core, but because Jupiter’s is “lumpy”, or stronger in some regions than in others, the gas giant’s magnetic field might be generated above its metallic hydrogen layer.

“Juno is giving us a view of the magnetic field close to Jupiter that we’ve never had before,” – Jack Connerney, Juno Deputy Principal Investigator

“Juno is giving us a view of the magnetic field close to Jupiter that we’ve never had before,” said Jack Connerney, Juno deputy principal investigator and the lead for the mission’s magnetic field investigation at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “Already we see that the magnetic field looks lumpy: it is stronger in some places and weaker in others. This uneven distribution suggests that the field might be generated by dynamo action closer to the surface, above the layer of metallic hydrogen. Every flyby we execute gets us closer to determining where and how Jupiter’s dynamo works.”

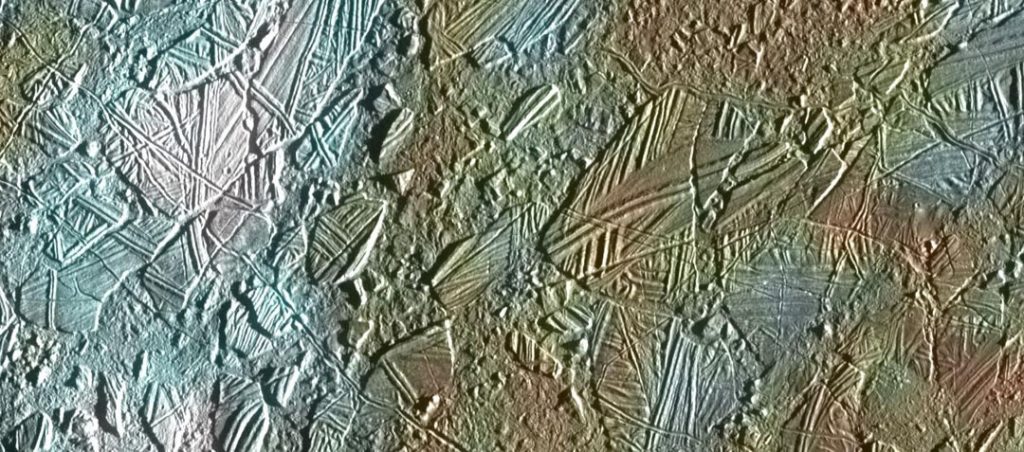

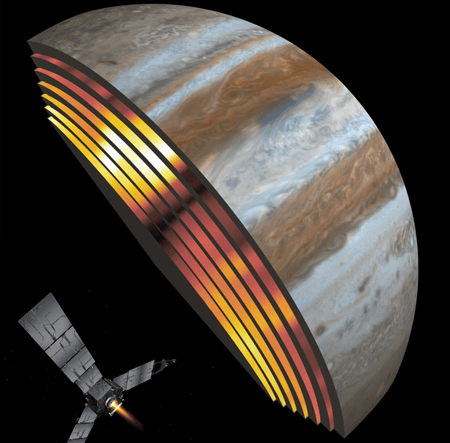

Jupiter’s Atmosphere

Juno’s Microwave Radiometer (MWR) is designed to probe Jupiter’s thick atmosphere. It can detect the thermal microwave radiation in the atmosphere, both at the surface, and much deeper. Data from the MWR shows us that the storm belts are mysteries themselves.

The belts near Jupiter’s equator extend deep into the atmosphere, while other belts seem to evolve and transform into other structures. The MWR can probe a few hundred kilometers into the atmosphere, where it has found variable and increasing amounts of ammonia to that depth.

Polar Regions and Auroras

Jupiter is home to intense aurora activity at both poles. One of Juno’s mission goals is to study those auroras and the powerful polar magnetic fields that create them. Initial observations from Juno suggest that they are formed differently than Earthly auroras.

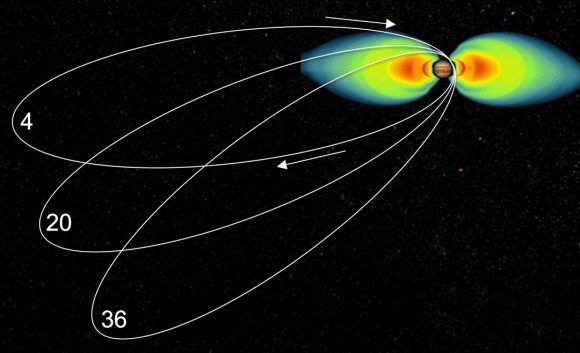

Juno is in a unique position to study the magnetosphere and the auroras. Its elongated polar orbit allows it to span the entire magnetosphere all the way from the bow shock to the planet itself.

According to the paper detailing the initial data on Jupiter’s magnetosphere an auroras, many of the observations have “terrestrial analogs.” But other aspects are very Jovian, and have no counterpart on Earth.

“…a radically different conceptual model of Jupiter’s interaction with its space environment.” – from J. E. P. Connerney et. al., 2017

As the authors say in their summary, “We observed plasmas upwelling from the ionosphere, providing a mechanism whereby Jupiter helps populate its magnetosphere. The weakness of the magnetic field-aligned electric currents associated with the main aurora and the broadly distributed nature of electron beaming in the polar caps suggest a radically different conceptual model of Jupiter’s interaction with its space environment.”

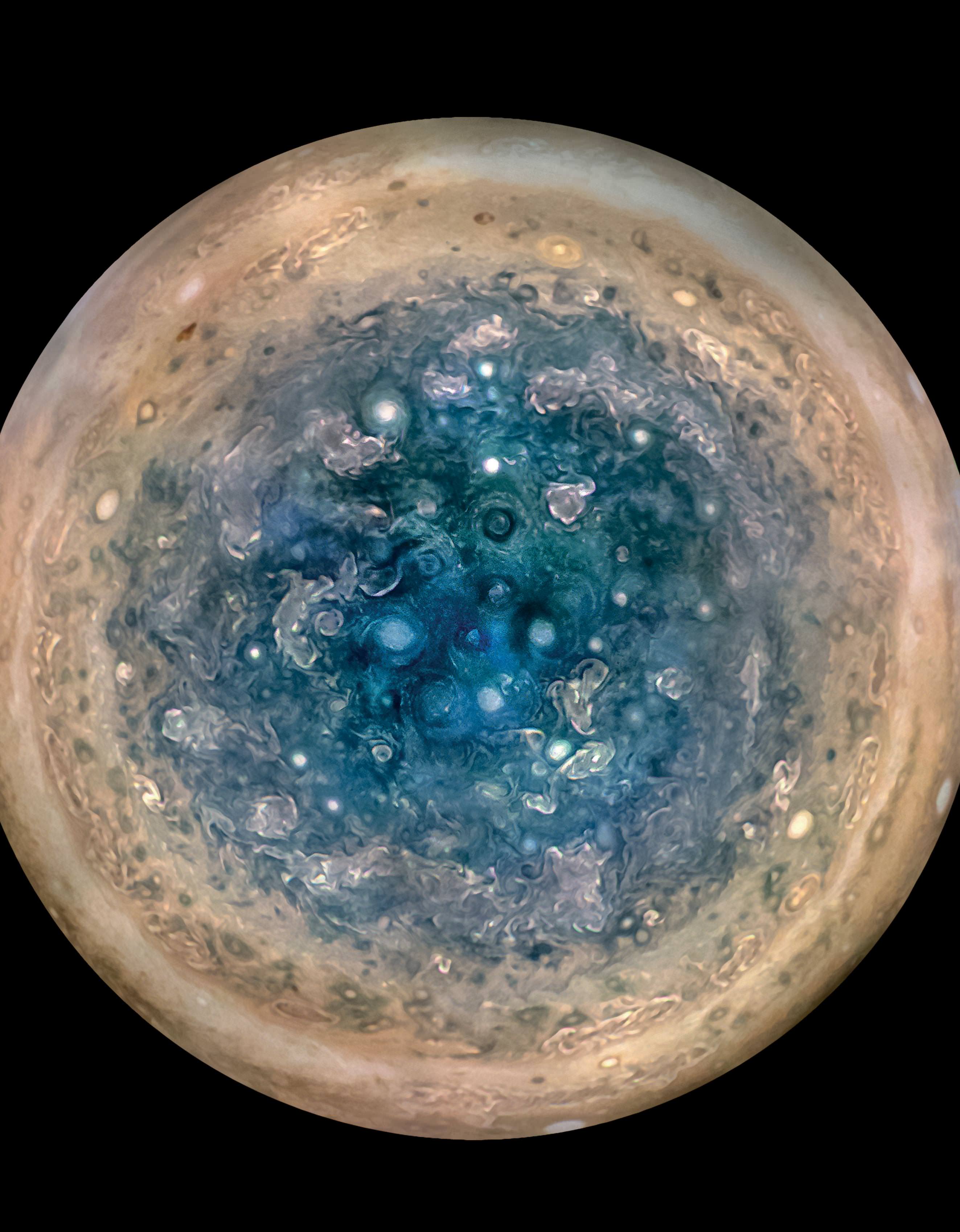

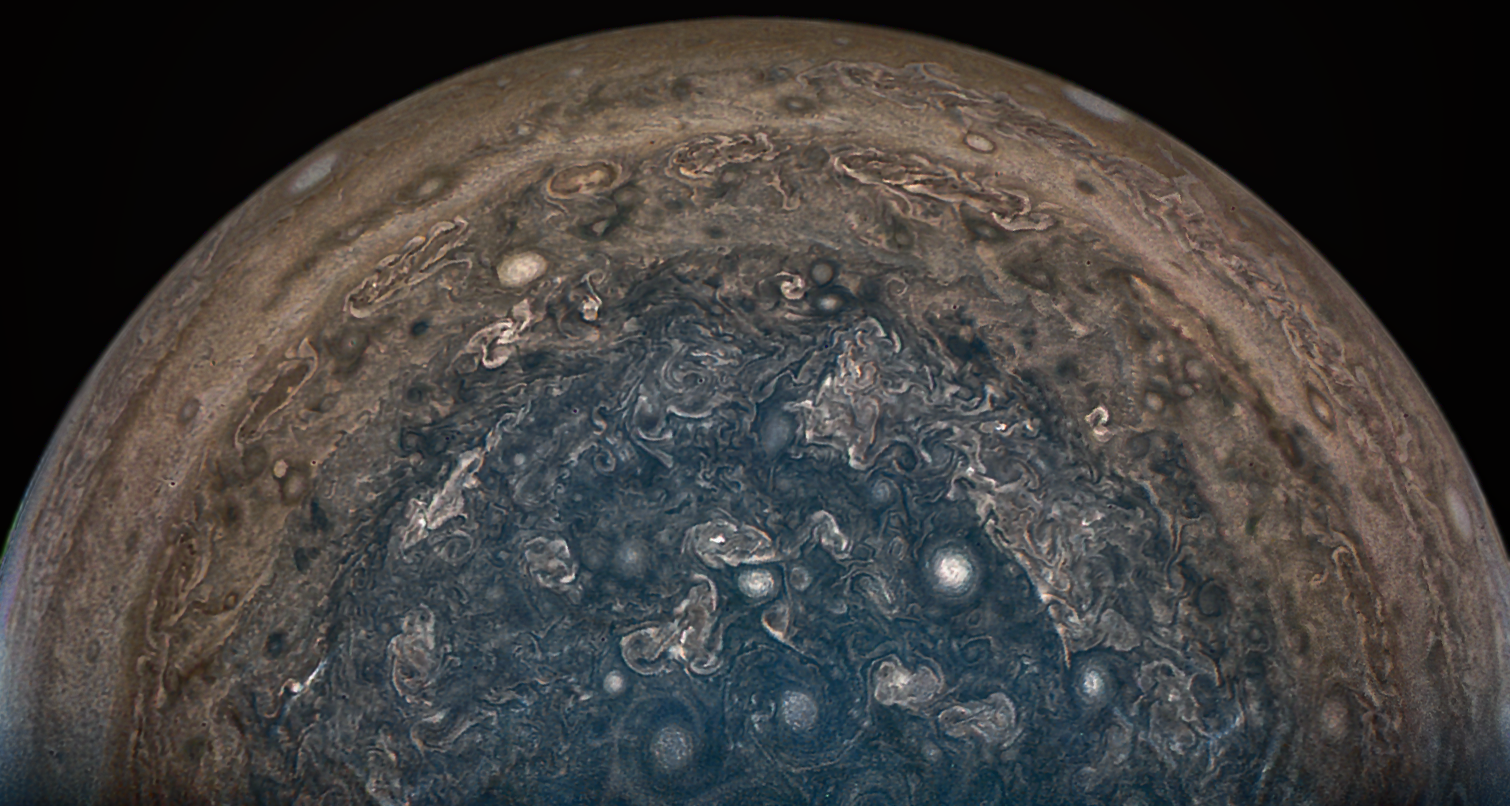

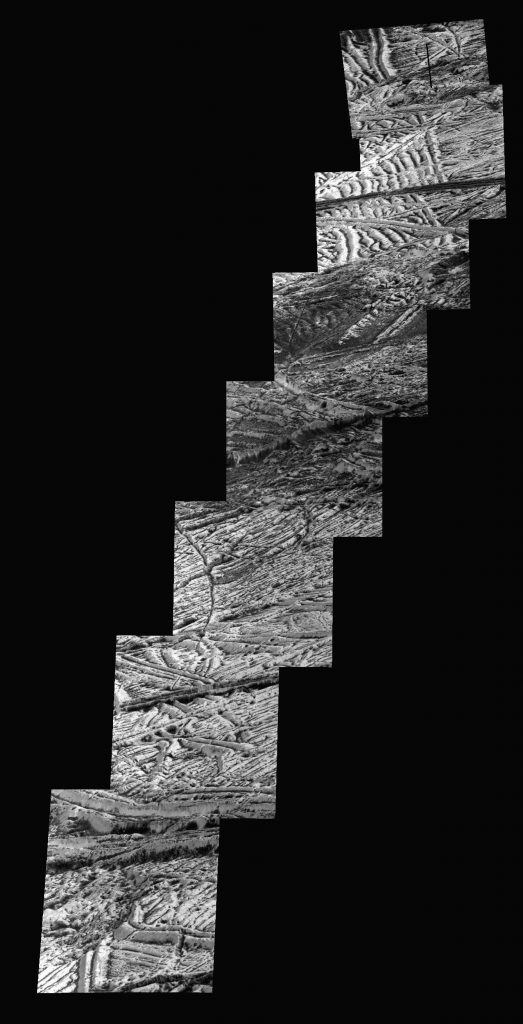

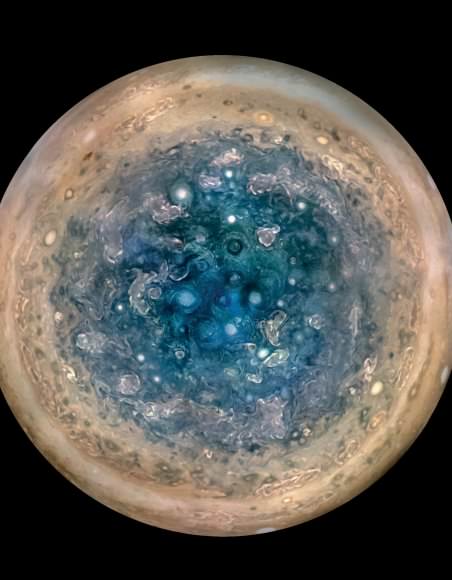

Polar Storms

JunoCam has also found some puzzling features in Jupiter’s atmosphere. The poles themselves are populated by densely clustered, swirling storms the size of Earth. Since they’ve only been observed briefly, there are a host of unanswered questions about them.

“We’re puzzled as to how they could be formed, how stable the configuration is, and why Jupiter’s north pole doesn’t look like the south pole.” – Scott Bolton, Juno’s Principal Investigator at the Southwest Research Institute

“We’re puzzled as to how they could be formed, how stable the configuration is, and why Jupiter’s north pole doesn’t look like the south pole,” said Bolton. “We’re questioning whether this is a dynamic system, and are we seeing just one stage, and over the next year, we’re going to watch it disappear, or is this a stable configuration and these storms are circulating around one another?”

The Great Red Spot: Juno’s Next Target

Juno’s purposeful orbit takes it extremely close to the cloud tops, where it can perform powerful science. But the orbit also takes it a long way from Jupiter. Every 53 days it takes another plunge at Jupiter, where it gathers its next set of observations.

“Every 53 days, we go screaming by Jupiter, get doused by a fire hose of Jovian science, and there is always something new.” – Scott Bolton, Juno’s Principal Investigator at the Southwest Research Institute.

“Every 53 days, we go screaming by Jupiter, get doused by a fire hose of Jovian science, and there is always something new,” said Bolton. “On our next flyby on July 11, we will fly directly over one of the most iconic features in the entire solar system — one that every school kid knows — Jupiter’s Great Red Spot. If anybody is going to get to the bottom of what is going on below those mammoth swirling crimson cloud tops, it’s Juno and her cloud-piercing science instruments.”

During each pass, Juno collects about 6 megabytes of data, which it sends back to Earth via the Deep Space Network. After that, the data is analyzed and published.

Juno has many more fly-bys of Jupiter before it’s sent to its end in the atmosphere of Jupiter. We can expect many more surprises, and hopefully some answers, between now and then.