It is an well-known fact that all stars have a lifespan. This begins with their formation, then continues through their Main Sequence phase (which constitutes the majority of their life) before ending in death. In most cases, stars will swell up to several hundred times their normal size as they exit the Main Sequence phase of their life, during which time they will likely consume any planets that orbit closely to them.

However, for planets that orbit the star at greater distances (beyond the system’s “Frost Line“, essentially), conditions might actually become warm enough for them to support life. And according to new research which comes from the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell University, this situation could last for some star systems into the billions of years, giving rise to entirely new forms of extra-terrestrial life!

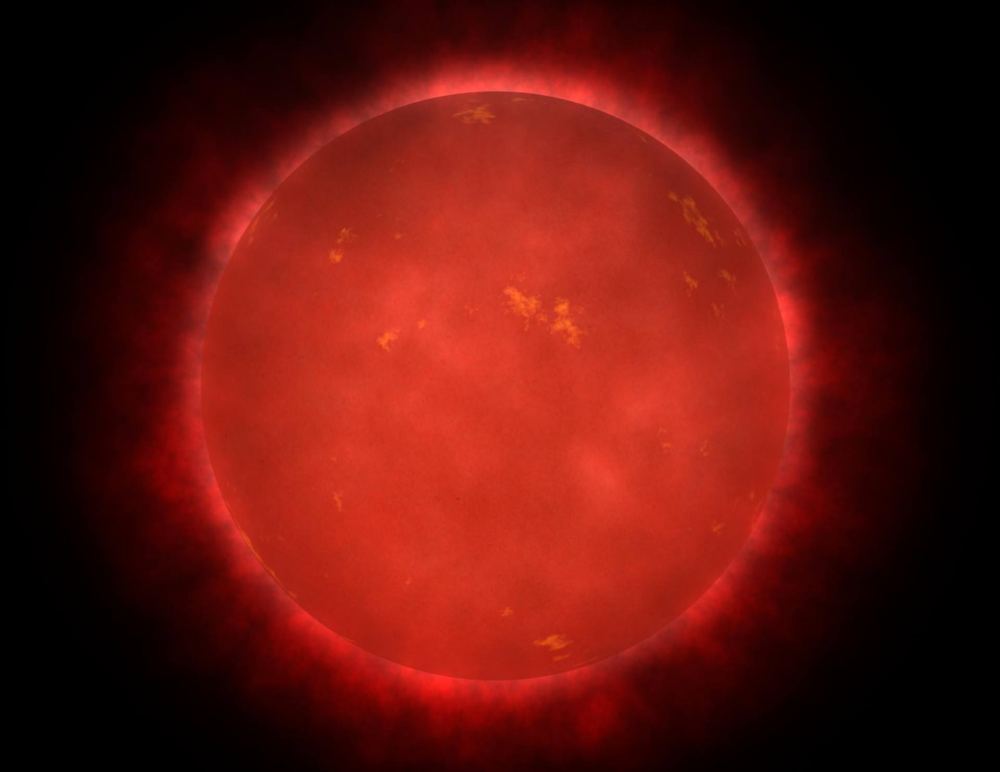

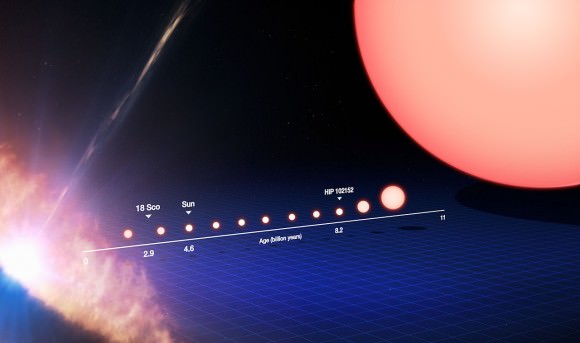

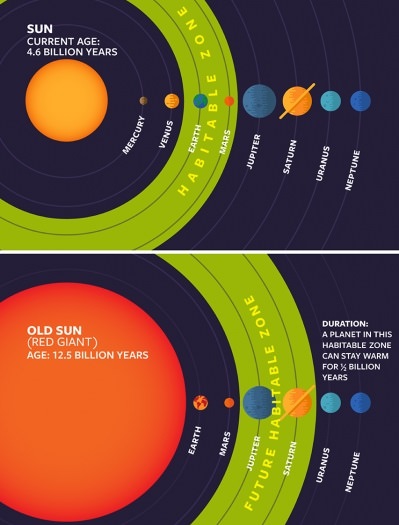

In approximately 5.4 billion years from now, our Sun will exit its Main Sequence phase. Having exhausted the hydrogen fuel in its core, the inert helium ash that has built up there will become unstable and collapse under its own weight. This will cause the core to heat up and get denser, which in turn will cause the Sun to grow in size and enter what is known as the Red Giant-Branch (RGB) phase of its evolution.

This period will begin with our Sun becoming a subgiant, in which it will slowly double in size over the course of about half a billion years. It will then spend the next half a billion years expanding more rapidly, until it is 200 times its current size and several thousands times more luminous. It will then officially be a red giant star, eventually expanding to the point where it reaches beyond Mars’ orbit.

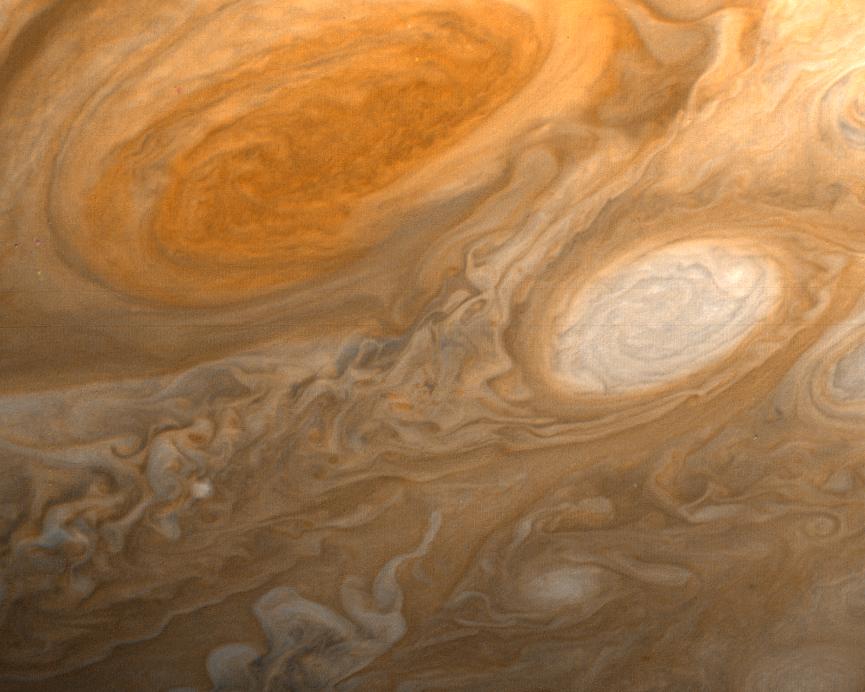

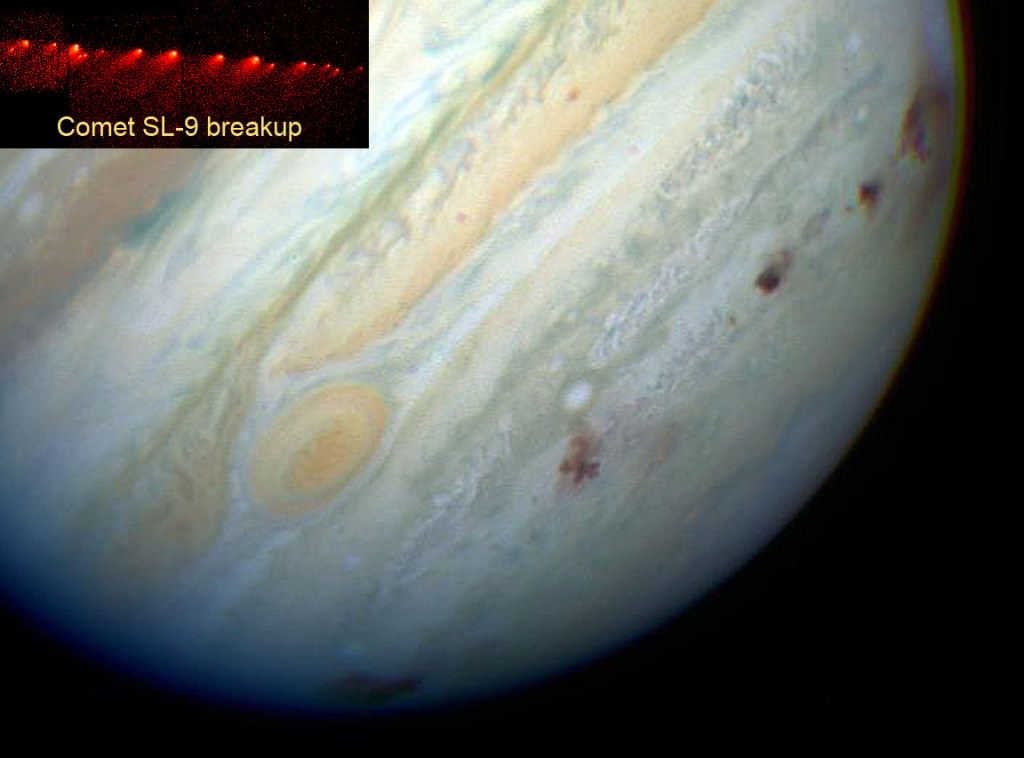

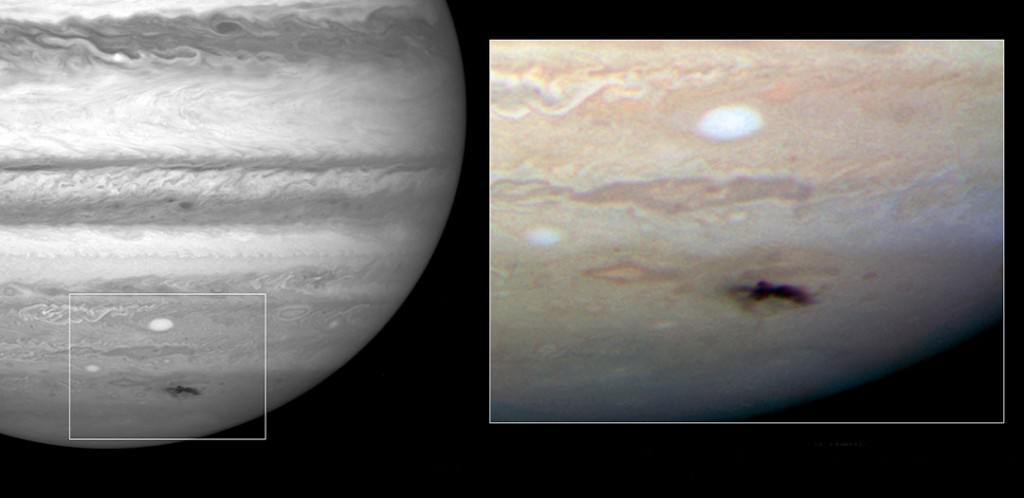

As we explored in a previous article, planet Earth will not survive our Sun becoming a Red Giant – nor will Mercury, Venus or Mars. But beyond the “Frost Line”, where it is cold enough that volatile compounds – such as water, ammonia, methane, carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide – remain in a frozen state, the remain gas giants, ice giants, and dwarf planets will survive. Not only that, but a massive thaw will set in.

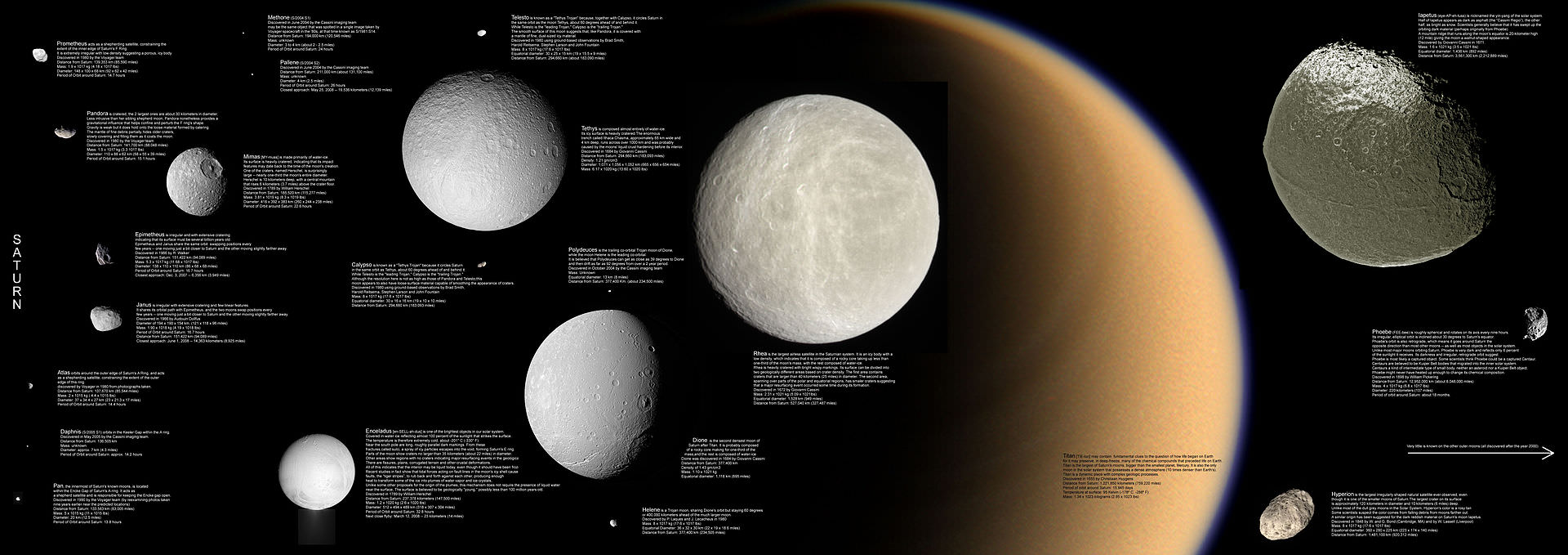

In short, when the star expands, its “habitable zone” will likely do the same, encompassing the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn. When this happens, formerly uninhabitable places – like the Jovian and Cronian moons – could suddenly become inhabitable. The same holds true for many other stars in the Universe, all of which are fated to become Red Giants as they near the end of their lifespans.

However, when our Sun reaches its Red Giant Branch phase, it is only expected to have 120 million years of active life left. This is not quite enough time for new lifeforms to emerge, evolve and become truly complex (i.e. like humans and other species of mammals). But according to a recent research study that appeared in The Astrophysical Journal – titled “Habitable Zone of Post-Main Sequence Stars” – some planets may be able to remain habitable around other red giant stars in our Universe for much longer – up to 9 billion years or more in some cases!

To put that in perspective, nine billion years is close to twice the current age of Earth. So assuming that the worlds in question also have the right mix of elements, they will have ample time to give rise to new and complex forms of life. The study’s co-author, Professor Lisa Kaltennegeris, is also the director of the Carl Sagan Institute. As such, she is no stranger to searching for life in other parts of the Universe. As she explained to Universe Today via email:

“We found that planets – depending on how big their Sun is (the smaller the star, the longer the planet can stay habitable) – can stay nice and warm for up to 9 Billion years. That makes an old star an interesting place to look for life. It could have started sub-surface (e.g. in a frozen ocean) and then when the ice melts, the gases that life breaths in and out can escape into the atmosphere – what allows astronomers to pick them up as signatures of life. Or for the smallest stars, the time a formerly frozen planet can be nice and warm is up to 9 billion years. Thus life could potentially even get started in that time.”

Using existing models of stars and their evolution – i.e. one-dimensional radiative-convective climate and stellar evolutionary models – for their study, Kaltenegger and Ramirez were able to calculate the distances of the habitable zones (HZ) around a series of post-Main Sequence (post-MS) stars. Ramses M. Ramirez – a research associate at the Carl Sagan Institute and the lead author of the paper – explained the research process to Universe Today via email:

“We used stellar evolutionary models that tell us how stellar quantities, mainly the brightness, radius, and temperature all change with time as the star ages through the red giant phase. We also used a climate model to then compute how much energy each star is outputting at the boundaries of the habitable zone. Knowing this and the stellar brightness mentioned above, we can compute the distances to these habitable zone boundaries.”

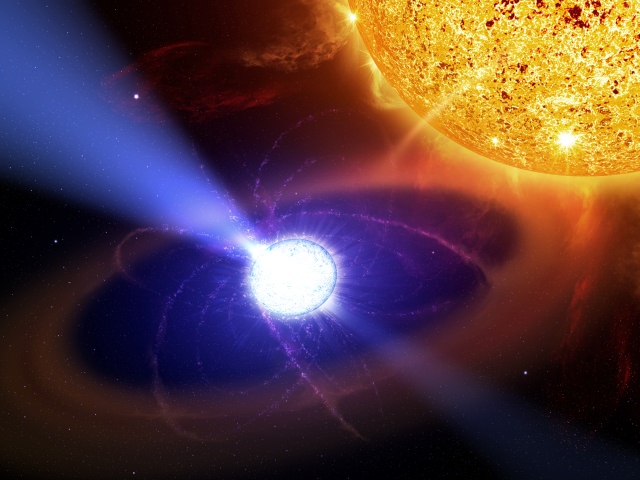

At the same time, they considered how this kind of stellar evolution could effect the atmosphere of the star’s planets. As a star expands, it loses mass and ejects it outward in the form of solar wind. For planets that orbit close to a star, or those that have low surface gravity, they may find some or all of their atmospheres blasted away. On the other hand, planets with sufficient mass (or positioned at a safe distance) could maintain most of their atmospheres.

“The stellar winds from this mass loss erodes planetary atmospheres, which we also compute as a function of time,” said Ramirez. “As the star loses mass, the solar system conserves angular momentum by moving outwards. So, we also take into account how the orbits move out with time.” By using models that incorporated the rate of stellar and atmospheric loss during the Red Giant Branch (RGB) and Asymptotic Giant Branch (AGB) phases of star, they were able to determine how this would play out for planets that ranged in size from super-Moons to super-Earths.

What they found was that a planet can stay in a post-HS HZ for eons or more, depending on how hot the star is, and figuring for metallicities that are similar to our Sun’s. As Ramirez explained:

“The main result is that the maximum time that a planet can remain in this red giant habitable zone of hot stars is 200 million years. For our coolest star (M1), the maximum time a planet can stay within this red giant habitable zone is 9 billion years. Those results assume metallicity levels similar to those of our Sun. A star with a higher percentage of metals takes longer to fuse the non-metals (H, He..etc) and so these maximum times can increase some more, up to about a factor of two.”

Within the context of our Solar System, this could mean that in a few billion years, worlds like Europa and Enceladus (which are already suspected of having life beneath their icy surfaces) might get a shot at becoming full-fledged habitable worlds. As Ramirez summarized beautifully:

“This means that the post-main-sequence is another potentially interesting phase of stellar evolution from a habitability standpoint. Long after the inner system of planets have been turned into sizzling wastelands by the expanding, growing red giant star, there could be potentially habitable abodes farther away from the chaos. If they are frozen worlds, like Europa, the ice would melt, potentially unveiling any preexisting life. Such pre-existing life may be detectable by future missions/telescopes looking for atmospheric biosignatures.”

But perhaps the most exciting take-away from their research study was their conclusion that planets orbiting within their star’s post-MS habitable zones would be doing so at distances that would make them detectable using direct imaging techniques. So not only are the odds of finding life around older stars better than previously thought, we should have no trouble in spotting them using current exoplanet-hunting techniques!

It is also worth noting that Kaltenegger and Dr. Ramirez have submitted a second paper for publication, in which they provide a list of 23 red giant stars within 100 light-years of Earth. Knowing that these stars, all of which are in our stellar neighborhood, could have life-sustaining worlds within their habitable zones should provide additional opportunities for planet hunters in the coming years.

And be sure to check out this video from Cornellcast, where Prof. Kaltenegger shares what inspires her scientific curiosity and how Cornell’s scientists are working to find proof of extra-terrestrial life.

Further Reading: The Astrophysical Journal