Here on Earth, we tend to take our atmosphere for granted, and not without reason. Our atmosphere has a lovely mix of nitrogen and oxygen (78% and 21% respectively) with trace amounts of water vapor, carbon dioxide and other gaseous molecules. What’s more, we enjoy an atmospheric pressure of 101.325 kPa, which extends to an altitude of about 8.5 km.

In short, our atmosphere is plentiful and life-sustaining. But what about the other planets of the Solar System? How do they stack up in terms of atmospheric composition and pressure? We know for a fact that they are not breathable by humans and cannot support life. But just what is the difference between these balls of rock and gas and our own?

For starters, it should be noted that every planet in the Solar System has an atmosphere of one kind or another. And these range from incredibly thin and tenuous (such as Mercury’s “exosphere”) to the incredibly dense and powerful – which is the case for all of the gas giants. And depending on the composition of the planet, whether it is a terrestrial or a gas/ice giant, the gases that make up its atmosphere range from either the hydrogen and helium to more complex elements like oxygen, carbon dioxide, ammonia and methane.

Mercury’s Atmosphere:

Mercury is too hot and too small to retain an atmosphere. However, it does have a tenuous and variable exosphere that is made up of hydrogen, helium, oxygen, sodium, calcium, potassium and water vapor, with a combined pressure level of about 10-14 bar (one-quadrillionth of Earth’s atmospheric pressure). It is believed this exosphere was formed from particles captured from the Sun, volcanic outgassing and debris kicked into orbit by micrometeorite impacts.

Because it lacks a viable atmosphere, Mercury has no way to retain the heat from the Sun. As a result of this and its high eccentricity, the planet experiences considerable variations in temperature. Whereas the side that faces the Sun can reach temperatures of up to 700 K (427° C), while the side in shadow dips down to 100 K (-173° C).

Venus’ Atmosphere:

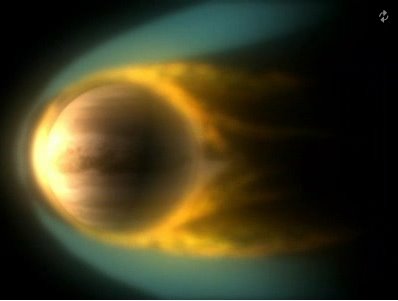

Surface observations of Venus have been difficult in the past, due to its extremely dense atmosphere, which is composed primarily of carbon dioxide with a small amount of nitrogen. At 92 bar (9.2 MPa), the atmospheric mass is 93 times that of Earth’s atmosphere and the pressure at the planet’s surface is about 92 times that at Earth’s surface.

Venus is also the hottest planet in our Solar System, with a mean surface temperature of 735 K (462 °C/863.6 °F). This is due to the CO²-rich atmosphere which, along with thick clouds of sulfur dioxide, generates the strongest greenhouse effect in the Solar System. Above the dense CO² layer, thick clouds consisting mainly of sulfur dioxide and sulfuric acid droplets scatter about 90% of the sunlight back into space.

Another common phenomena is Venus’ strong winds, which reach speeds of up to 85 m/s (300 km/h; 186.4 mph) at the cloud tops and circle the planet every four to five Earth days. At this speed, these winds move up to 60 times the speed of the planet’s rotation, whereas Earth’s fastest winds are only 10-20% of the planet’s rotational speed.

Venus flybys have also indicated that its dense clouds are capable of producing lightning, much like the clouds on Earth. Their intermittent appearance indicates a pattern associated with weather activity, and the lightning rate is at least half of that on Earth.

Earth’s Atmosphere:

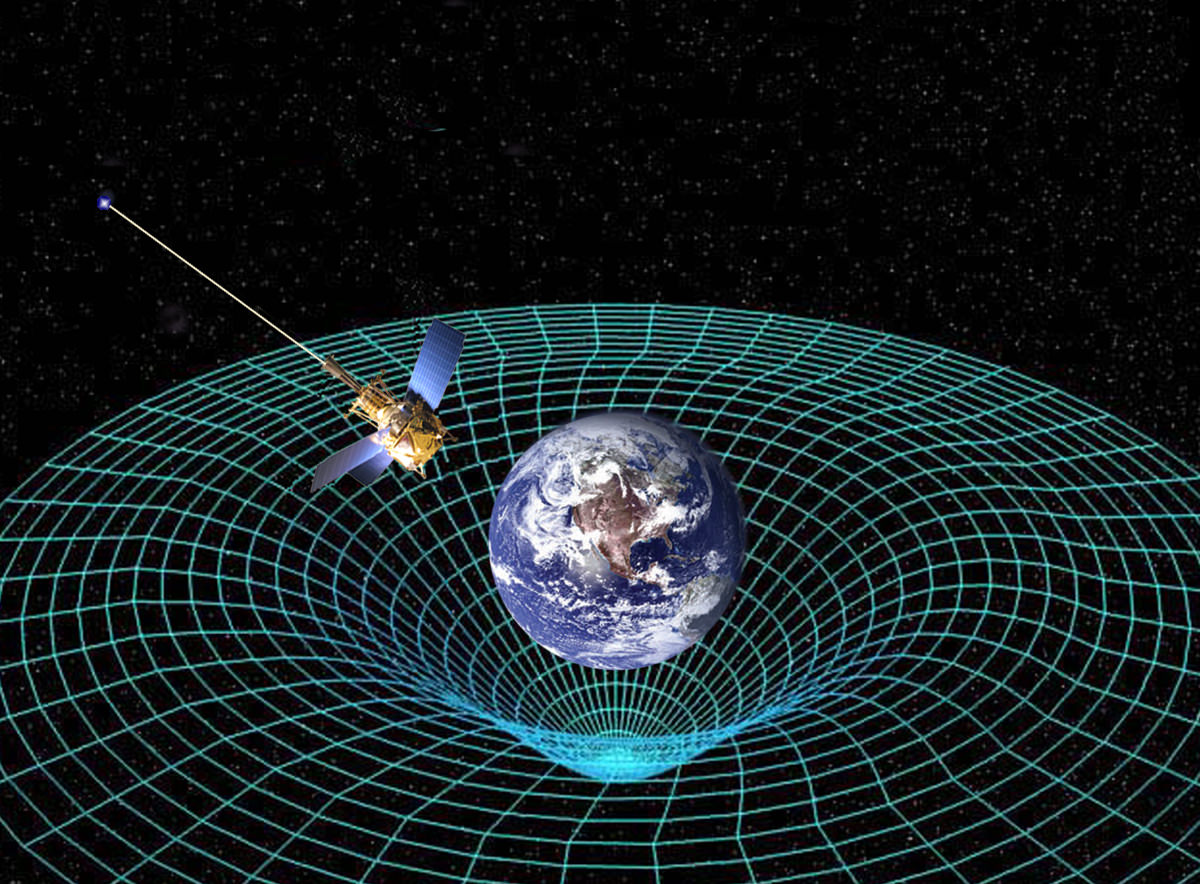

Earth’s atmosphere, which is composed of nitrogen, oxygen, water vapor, carbon dioxide and other trace gases, also consists of five layers. These consists of the Troposphere, the Stratosphere, the Mesosphere, the Thermosphere, and the Exosphere. As a rule, air pressure and density decrease the higher one goes into the atmosphere and the farther one is from the surface.

Closest to the Earth is the Troposphere, which extends from the 0 to between 12 km and 17 km (0 to 7 and 10.56 mi) above the surface. This layer contains roughly 80% of the mass of Earth’s atmosphere, and nearly all atmospheric water vapor or moisture is found in here as well. As a result, it is the layer where most of Earth’s weather takes place.

The Stratosphere extends from the Troposphere to an altitude of 50 km (31 mi). This layer extends from the top of the troposphere to the stratopause, which is at an altitude of about 50 to 55 km (31 to 34 mi). This layer of the atmosphere is home to the ozone layer, which is the part of Earth’s atmosphere that contains relatively high concentrations of ozone gas.

![Space Shuttle Endeavour sillouetted against the atmosphere. The orange layer is the troposphere, the white layer is the stratosphere and the blue layer the mesosphere.[1] (The shuttle is actually orbiting at an altitude of more than 320 km (200 mi), far above all three layers.) Credit: NASA](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Endeavour_silhouette_STS-130-580x387.jpg)

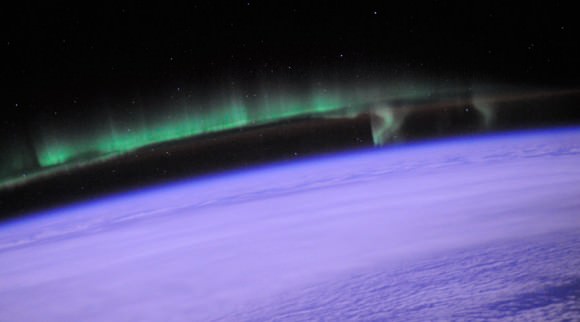

The lower part of the thermosphere, from 80 to 550 kilometers (50 to 342 mi), contains the ionosphere – which is so named because it is here in the atmosphere that particles are ionized by solar radiation. This layer is completely cloudless and free of water vapor. It is also at this altitude that the phenomena known as Aurora Borealis and Aurara Australis are known to take place.

The Exosphere, which is outermost layer of the Earth’s atmosphere, extends from the exobase – located at the top of the thermosphere at an altitude of about 700 km above sea level – to about 10,000 km (6,200 mi). The exosphere merges with the emptiness of outer space, and is mainly composed of extremely low densities of hydrogen, helium and several heavier molecules including nitrogen, oxygen and carbon dioxide

The exosphere is located too far above Earth for any meteorological phenomena to be possible. However, the Aurora Borealis and Aurora Australis sometimes occur in the lower part of the exosphere, where they overlap into the thermosphere.

The average surface temperature on Earth is approximately 14°C; but as already noted, this varies. For instance, the hottest temperature ever recorded on Earth was 70.7°C (159°F), which was taken in the Lut Desert of Iran. Meanwhile, the coldest temperature ever recorded on Earth was measured at the Soviet Vostok Station on the Antarctic Plateau, reaching an historic low of -89.2°C (-129°F).

Mars’ Atmosphere:

Planet Mars has a very thin atmosphere which is composed of 96% carbon dioxide, 1.93% argon and 1.89% nitrogen along with traces of oxygen and water. The atmosphere is quite dusty, containing particulates that measure 1.5 micrometers in diameter, which is what gives the Martian sky a tawny color when seen from the surface. Mars’ atmospheric pressure ranges from 0.4 – 0.87 kPa, which is equivalent to about 1% of Earth’s at sea level.

Because of its thin atmosphere, and its greater distance from the Sun, the surface temperature of Mars is much colder than what we experience here on Earth. The planet’s average temperature is -46 °C (51 °F), with a low of -143 °C (-225.4 °F) during the winter at the poles, and a high of 35 °C (95 °F) during summer and midday at the equator.

The planet also experiences dust storms, which can turn into what resembles small tornadoes. Larger dust storms occur when the dust is blown into the atmosphere and heats up from the Sun. The warmer dust filled air rises and the winds get stronger, creating storms that can measure up to thousands of kilometers in width and last for months at a time. When they get this large, they can actually block most of the surface from view.

Trace amounts of methane have also been detected in the Martian atmosphere, with an estimated concentration of about 30 parts per billion (ppb). It occurs in extended plumes, and the profiles imply that the methane was released from specific regions – the first of which is located between Isidis and Utopia Planitia (30°N 260°W) and the second in Arabia Terra (0°N 310°W).

Ammonia was also tentatively detected on Mars by the Mars Express satellite, but with a relatively short lifetime. It is not clear what produced it, but volcanic activity has been suggested as a possible source.

Jupiter’s Atmosphere:

Much like Earth, Jupiter experiences auroras near its northern and southern poles. But on Jupiter, the auroral activity is much more intense and rarely ever stops. The intense radiation, Jupiter’s magnetic field, and the abundance of material from Io’s volcanoes that react with Jupiter’s ionosphere create a light show that is truly spectacular.

Jupiter also experiences violent weather patterns. Wind speeds of 100 m/s (360 km/h) are common in zonal jets, and can reach as high as 620 kph (385 mph). Storms form within hours and can become thousands of km in diameter overnight. One storm, the Great Red Spot, has been raging since at least the late 1600s. The storm has been shrinking and expanding throughout its history; but in 2012, it was suggested that the Giant Red Spot might eventually disappear.

Jupiter is perpetually covered with clouds composed of ammonia crystals and possibly ammonium hydrosulfide. These clouds are located in the tropopause and are arranged into bands of different latitudes, known as “tropical regions”. The cloud layer is only about 50 km (31 mi) deep, and consists of at least two decks of clouds: a thick lower deck and a thin clearer region.

There may also be a thin layer of water clouds underlying the ammonia layer, as evidenced by flashes of lightning detected in the atmosphere of Jupiter, which would be caused by the water’s polarity creating the charge separation needed for lightning. Observations of these electrical discharges indicate that they can be up to a thousand times as powerful as those observed here on the Earth.

Saturn’s Atmosphere:

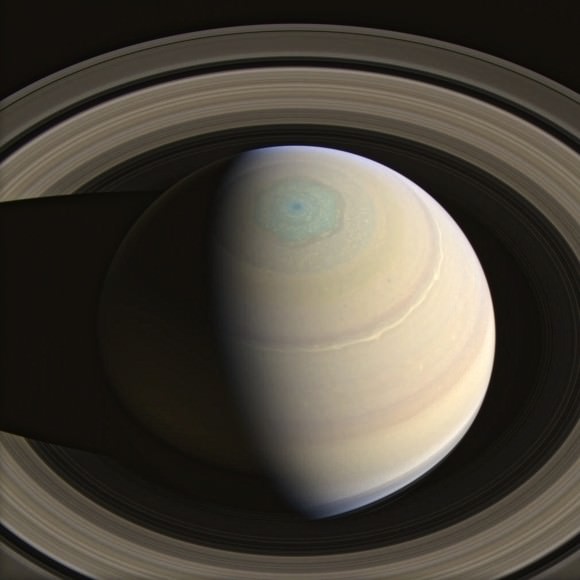

The outer atmosphere of Saturn contains 96.3% molecular hydrogen and 3.25% helium by volume. The gas giant is also known to contain heavier elements, though the proportions of these relative to hydrogen and helium is not known. It is assumed that they would match the primordial abundance from the formation of the Solar System.

Trace amounts of ammonia, acetylene, ethane, propane, phosphine and methane have been also detected in Saturn’s atmosphere. The upper clouds are composed of ammonia crystals, while the lower level clouds appear to consist of either ammonium hydrosulfide (NH4SH) or water. Ultraviolet radiation from the Sun causes methane photolysis in the upper atmosphere, leading to a series of hydrocarbon chemical reactions with the resulting products being carried downward by eddies and diffusion.

Saturn’s atmosphere exhibits a banded pattern similar to Jupiter’s, but Saturn’s bands are much fainter and wider near the equator. As with Jupiter’s cloud layers, they are divided into the upper and lower layers, which vary in composition based on depth and pressure. In the upper cloud layers, with temperatures in range of 100–160 K and pressures between 0.5–2 bar, the clouds consist of ammonia ice.

Water ice clouds begin at a level where the pressure is about 2.5 bar and extend down to 9.5 bar, where temperatures range from 185–270 K. Intermixed in this layer is a band of ammonium hydrosulfide ice, lying in the pressure range 3–6 bar with temperatures of 290–235 K. Finally, the lower layers, where pressures are between 10–20 bar and temperatures are 270–330 K, contains a region of water droplets with ammonia in an aqueous solution.

On occasion, Saturn’s atmosphere exhibits long-lived ovals, similar to what is commonly observed on Jupiter. Whereas Jupiter has the Great Red Spot, Saturn periodically has what’s known as the Great White Spot (aka. Great White Oval). This unique but short-lived phenomenon occurs once every Saturnian year, roughly every 30 Earth years, around the time of the northern hemisphere’s summer solstice.

These spots can be several thousands of kilometers wide, and have been observed in 1876, 1903, 1933, 1960, and 1990. Since 2010, a large band of white clouds called the Northern Electrostatic Disturbance have been observed enveloping Saturn, which was spotted by the Cassini space probe. If the periodic nature of these storms is maintained, another one will occur in about 2020.

The winds on Saturn are the second fastest among the Solar System’s planets, after Neptune’s. Voyager data indicate peak easterly winds of 500 m/s (1800 km/h). Saturn’s northern and southern poles have also shown evidence of stormy weather. At the north pole, this takes the form of a hexagonal wave pattern, whereas the south shows evidence of a massive jet stream.

The persisting hexagonal wave pattern around the north pole was first noted in the Voyager images. The sides of the hexagon are each about 13,800 km (8,600 mi) long (which is longer than the diameter of the Earth) and the structure rotates with a period of 10h 39m 24s, which is assumed to be equal to the period of rotation of Saturn’s interior.

The south pole vortex, meanwhile, was first observed using the Hubble Space Telescope. These images indicated the presence of a jet stream, but not a hexagonal standing wave. These storms are estimated to be generating winds of 550 km/h, are comparable in size to Earth, and believed to have been going on for billions of years. In 2006, the Cassini space probe observed a hurricane-like storm that had a clearly defined eye. Such storms had not been observed on any planet other than Earth – even on Jupiter.

Uranus’ Atmosphere:

As with Earth, the atmosphere of Uranus is broken into layers, depending upon temperature and pressure. Like the other gas giants, the planet doesn’t have a firm surface, and scientists define the surface as the region where the atmospheric pressure exceeds one bar (the pressure found on Earth at sea level). Anything accessible to remote-sensing capability – which extends down to roughly 300 km below the 1 bar level – is also considered to be the atmosphere.

Using these references points, Uranus’ atmosphere can be divided into three layers. The first is the troposphere, between altitudes of -300 km below the surface and 50 km above it, where pressures range from 100 to 0.1 bar (10 MPa to 10 kPa). The second layer is the stratosphere, which reaches between 50 and 4000 km and experiences pressures between 0.1 and 10-10 bar (10 kPa to 10 µPa).

The troposphere is the densest layer in Uranus’ atmosphere. Here, the temperature ranges from 320 K (46.85 °C/116 °F) at the base (-300 km) to 53 K (-220 °C/-364 °F) at 50 km, with the upper region being the coldest in the solar system. The tropopause region is responsible for the vast majority of Uranus’s thermal infrared emissions, thus determining its effective temperature of 59.1 ± 0.3 K.

Within the troposphere are layers of clouds – water clouds at the lowest pressures, with ammonium hydrosulfide clouds above them. Ammonia and hydrogen sulfide clouds come next. Finally, thin methane clouds lay on the top.

In the stratosphere, temperatures range from 53 K (-220 °C/-364 °F) at the upper level to between 800 and 850 K (527 – 577 °C/980 – 1070 °F) at the base of the thermosphere, thanks largely to heating caused by solar radiation. The stratosphere contains ethane smog, which may contribute to the planet’s dull appearance. Acetylene and methane are also present, and these hazes help warm the stratosphere.

The outermost layer, the thermosphere and corona, extend from 4,000 km to as high as 50,000 km from the surface. This region has a uniform temperature of 800-850 (577 °C/1,070 °F), although scientists are unsure as to the reason. Because the distance to Uranus from the Sun is so great, the amount of sunlight absorbed cannot be the primary cause.

Like Jupiter and Saturn, Uranus’s weather follows a similar pattern where systems are broken up into bands that rotate around the planet, which are driven by internal heat rising to the upper atmosphere. As a result, winds on Uranus can reach up to 900 km/h (560 mph), creating massive storms like the one spotted by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2012. Similar to Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, this “Dark Spot” was a giant cloud vortex that measured 1,700 kilometers by 3,000 kilometers (1,100 miles by 1,900 miles).

Neptune’s Atmosphere:

At high altitudes, Neptune’s atmosphere is 80% hydrogen and 19% helium, with a trace amount of methane. As with Uranus, this absorption of red light by the atmospheric methane is part of what gives Neptune its blue hue, although Neptune’s is darker and more vivid. Because Neptune’s atmospheric methane content is similar to that of Uranus, some unknown constituent is thought to contribute to Neptune’s more intense coloring.

Neptune’s atmosphere is subdivided into two main regions: the lower troposphere (where temperature decreases with altitude), and the stratosphere (where temperature increases with altitude). The boundary between the two, the tropopause, lies at a pressure of 0.1 bars (10 kPa). The stratosphere then gives way to the thermosphere at a pressure lower than 10-5 to 10-4 microbars (1 to 10 Pa), which gradually transitions to the exosphere.

Neptune’s spectra suggest that its lower stratosphere is hazy due to condensation of products caused by the interaction of ultraviolet radiation and methane (i.e. photolysis), which produces compounds such as ethane and ethyne. The stratosphere is also home to trace amounts of carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide, which are responsible for Neptune’s stratosphere being warmer than that of Uranus.

For reasons that remain obscure, the planet’s thermosphere experiences unusually high temperatures of about 750 K (476.85 °C/890 °F). The planet is too far from the Sun for this heat to be generated by ultraviolet radiation, which means another heating mechanism is involved – which could be the atmosphere’s interaction with ion’s in the planet’s magnetic field, or gravity waves from the planet’s interior that dissipate in the atmosphere.

Because Neptune is not a solid body, its atmosphere undergoes differential rotation. The wide equatorial zone rotates with a period of about 18 hours, which is slower than the 16.1-hour rotation of the planet’s magnetic field. By contrast, the reverse is true for the polar regions where the rotation period is 12 hours.

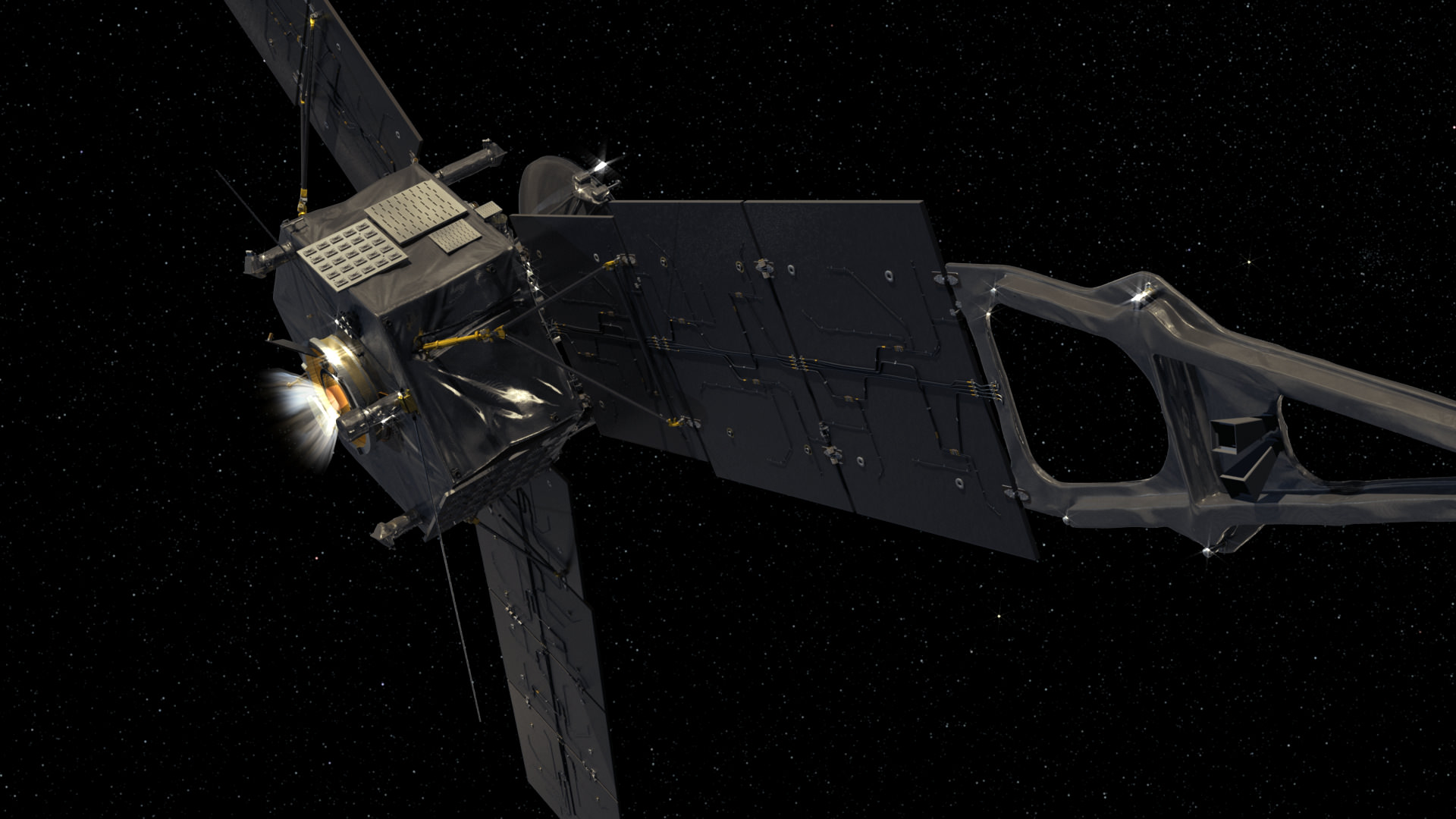

This differential rotation is the most pronounced of any planet in the Solar System, and results in strong latitudinal wind shear and violent storms. The three most impressive were all spotted in 1989 by the Voyager 2 space probe, and then named based on their appearances.

The first to be spotted was a massive anticyclonic storm measuring 13,000 x 6,600 km and resembling the Great Red Spot of Jupiter. Known as the Great Dark Spot, this storm was not spotted five later (Nov. 2nd, 1994) when the Hubble Space Telescope looked for it. Instead, a new storm that was very similar in appearance was found in the planet’s northern hemisphere, suggesting that these storms have a shorter life span than Jupiter’s.

The Scooter is another storm, a white cloud group located farther south than the Great Dark Spot – a nickname that first arose during the months leading up to the Voyager 2 encounter in 1989. The Small Dark Spot, a southern cyclonic storm, was the second-most-intense storm observed during the 1989 encounter. It was initially completely dark; but as Voyager 2 approached the planet, a bright core developed and could be seen in most of the highest-resolution images.

In sum, the planet’s of our Solar System all have atmospheres of sorts. And compared to Earth’s relatively balmy and thick atmosphere, they run the gamut between very very thin to very very dense. They also range in temperatures from the extremely hot (like on Venus) to the extreme freezing cold.

And when it comes to weather systems, things can equally extreme, with planet’s boasting either weather at all, or intense cyclonic and dust storms that put storms here n Earth to shame. And whereas some are entirely hostile to life as we know it, others we might be able to work with.

We have many interesting articles about planetary atmosphere’s here at Universe Today. For instance, he’s What is the Atmosphere?, and articles about the atmosphere of Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune,

For more information on atmospheres, check out NASA’s pages on Earth’s Atmospheric Layers, The Carbon Cycle, and how Earth’s atmosphere differs from space.

Astronomy Cast has an episode on the source of the atmosphere.