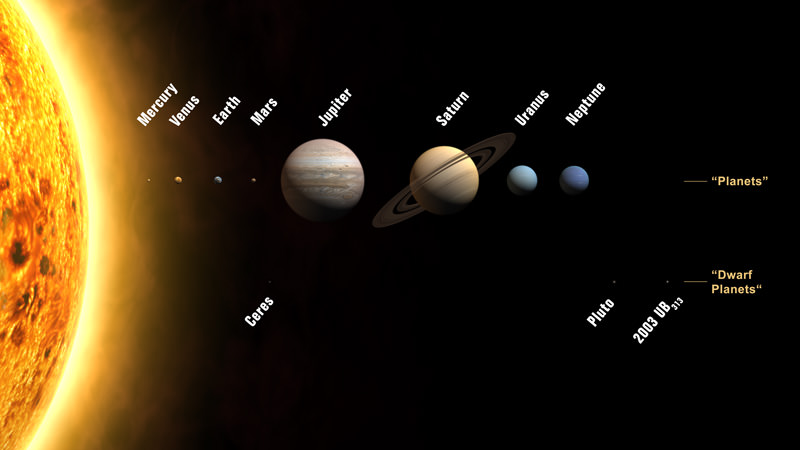

Our Solar System is a pretty picturesque place. Between the Sun, the Moon, and the Inner and Outer Solar System, there is no shortage of wondrous things to behold. But arguably, it is the eight planets that make up our Solar System that are the most interesting and photogenic. With their spherical discs, surface patterns and curious geological formations, Earth’s neighbors have been a subject of immense fascination for astronomers and scientists for millennia.

And in the age of modern astronomy, which goes beyond terrestrial telescopes to space telescopes, orbiters and satellites, there is no shortage of pictures of the planets. But here are a few of the better ones, taken with high-resolutions cameras on board spacecraft that managed to capture their intricate, picturesque, and rugged beauty.

Named after the winged messenger of the gods, Mercury is the closest planet to our Sun. It’s also the smallest (now that Pluto is no longer considered a planet. At 4,879 km, it is actually smaller than the Jovian moon of Ganymede and Saturn’s largest moon, Titan.

Because of its slow rotation and tenuous atmosphere, the planet experiences extreme variations in temperature – ranging from -184 °C on the dark side and 465 °C on the side facing the Sun. Because of this, its surface is barren and sun-scorched, as seen in the image above provided by the MESSENGER spacecraft.

Venus is the second planet from our Sun, and Earth’s closest neighboring planet. It also has the dubious honor of being the hottest planet in the Solar System. While farther away from the Sun than Mercury, it has a thick atmosphere made up primarily of carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide and nitrogen gas. This causes the Sun’s heat to become trapped, pushing average temperatures up to as high as 460°C. Due to the presence of sulfuric and carbonic compounds in the atmosphere, the planet’s atmosphere also produces rainstorms of sulfuric acid.

Because of its thick atmosphere, scientists were unable to examine of the surface of the planet until 1970s and the development of radar imaging. Since that time, numerous ground-based and orbital imaging surveys have produced information on the surface, particularly by the Magellan spacecraft (1990-94). The pictures sent back by Magellan revealed a harsh landscape dominated by lava flows and volcanoes, further adding to Venus’ inhospitable reputation.

Earth is the third planet from the Sun, the densest planet in our Solar System, and the fifth largest planet. Not only is 70% of the Earth’s surface covered with water, but the planet is also in the perfect spot – in the center of the hypothetical habitable zone – to support life. It’s atmosphere is primarily composed of nitrogen and oxygen and its average surface temperatures is 7.2°C. Hence why we call it home.

Being that it is our home, observing the planet as a whole was impossible prior to the space age. However, images taken by numerous satellites and spacecraft – such as the Apollo 11 mission, shown above – have been some of the most breathtaking and iconic in history.

Mars is the fourth planet from our Sun and Earth’s second closest neighbor. Roughly half the size of Earth, Mars is much colder than Earth, but experiences quite a bit of variability, with temperatures ranging from 20 °C at the equator during midday, to as low as -153 °C at the poles. This is due in part to Mars’ distance from the Sun, but also to its thin atmosphere which is not able to retain heat.

Mars is famous for its red color and the speculation it has sparked about life on other planets. This red color is caused by iron oxide – rust – which is plentiful on the planet’s surface. It’s surface features, which include long “canals”, have fueled speculation that the planet was home to a civilization.

Observations made by satellites flybys in the 1960’s (by the Mariner 3 and 4 spacecraft) dispelled this notion, but scientists still believe that warm, flowing water once existed on the surface, as well as organic molecules. Since that time, a small army of spacecraft and rovers have taken the Martian surface, and have produced some of the most detailed and beautiful photos of the planet to date.

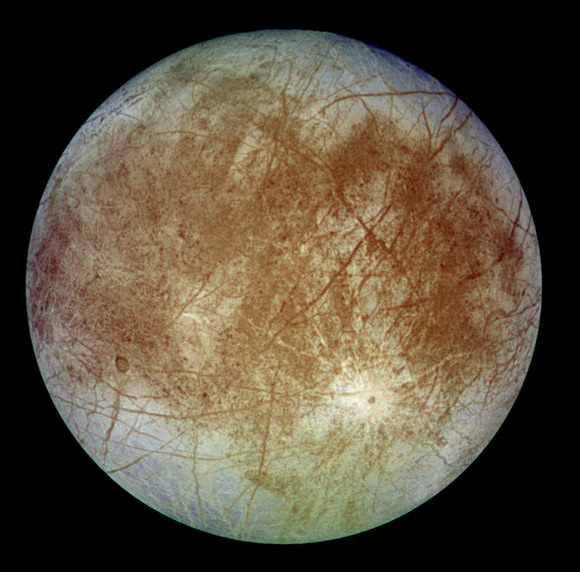

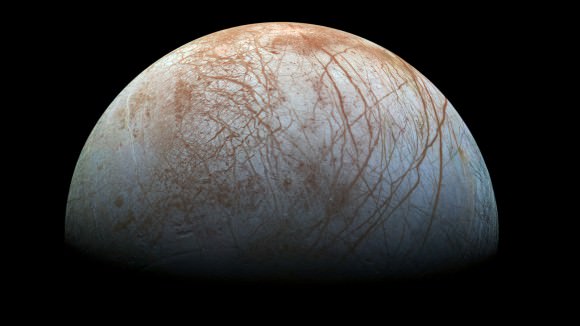

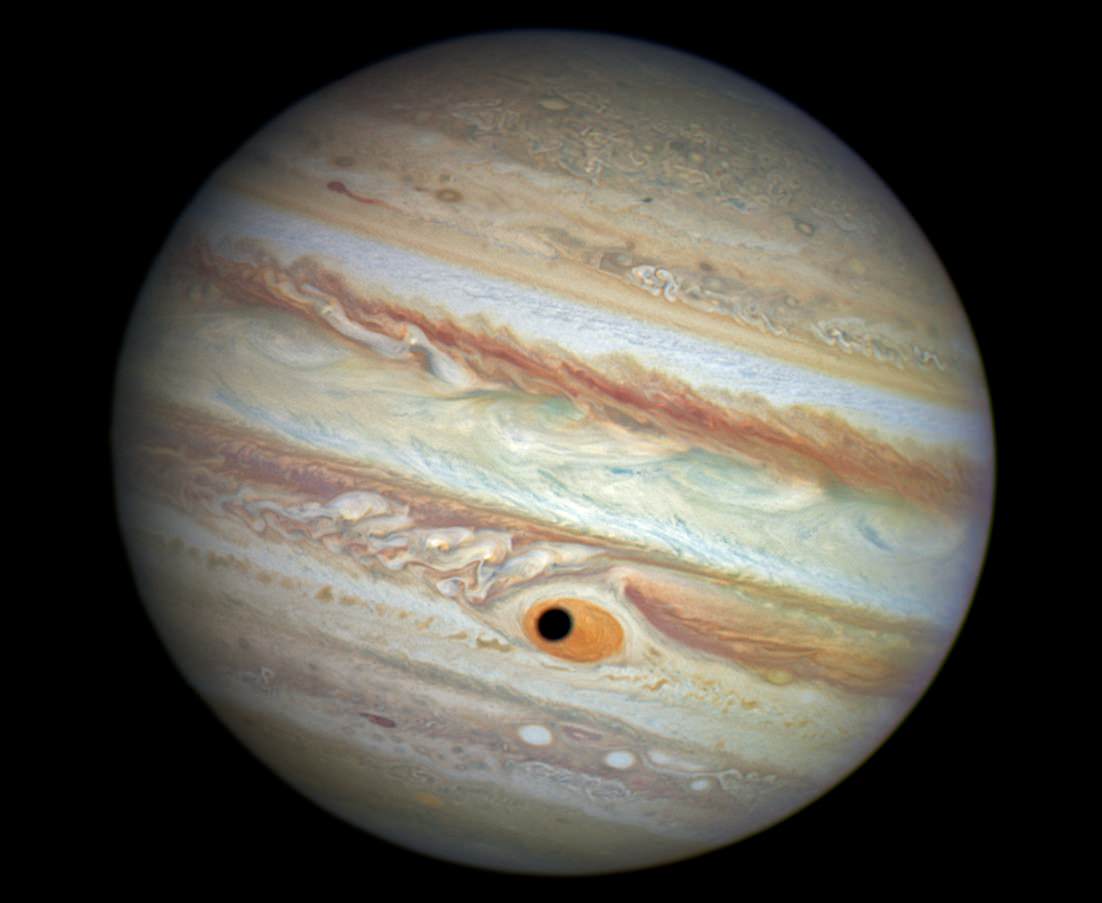

Jupiter, the closest gas giant to our Sun, is also the largest planet in the Solar System. Measuring over 70,000 km in radius, it is 317 times more massive than Earth and 2.5 times more massive than all the other planets in our Solar System combined. It also has the most moons of any planet in the Solar System, with 67 confirmed satellites as of 2012.

Despite its size, Jupiter is not very dense. The planet is comprised almost entirely of gas, with what astronomers believe is a core of metallic hydrogen. Yet, the sheer amount of pressure, radiation, gravitational pull and storm activity of this planet make it the undisputed titan of our Solar System.

Jupiter has been imaged by ground-based telescopes, space telescopes, and orbiter spacecraft. The best ground-based picture was taken in 2008 by the ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VTL) using its Multi-Conjugate Adaptive Optics Demonstrator (MAD) instrument. However, the greatest images captured of the Jovian giant were taken during flybys, in this case by the Galileo and Cassini missions.

Saturn, the second gas giant closest to our Sun, is best known for its ring system – which is composed of rocks, dust, and other materials. All gas giants have their own system of rings, but Saturn’s system is the most visible and photogenic. The planet is also the second largest in our Solar System, and is second only to Jupiter in terms of moons (62 confirmed).

Much like Jupiter, numerous pictures have been taken of the planet by a combination of ground-based telescopes, space telescopes and orbital spacecraft. These include the Pioneer, Voyager, and most recently, Cassini spacecraft.

Another gas giant, Uranus is the seventh planet from our Sun and the third largest planet in our Solar System. The planet contains roughly 14.5 times the mass of the Earth, but it has a low density. Scientists believe it is composed of a rocky core that is surrounded by an icy mantle made up of water, ammonia and methane ice, which is itself surrounded by an outer gaseous atmosphere of hydrogen and helium.

It is for this reason that Uranus is often referred to as an “ice planet”. The concentrations of methane are also what gives Uranus its blue color. Though telescopes have captured images of the planet, only one spacecraft has even taken pictures of Uranus over the years. This was the Voyager 2 craft which performed a flyby of the planet in 1986.

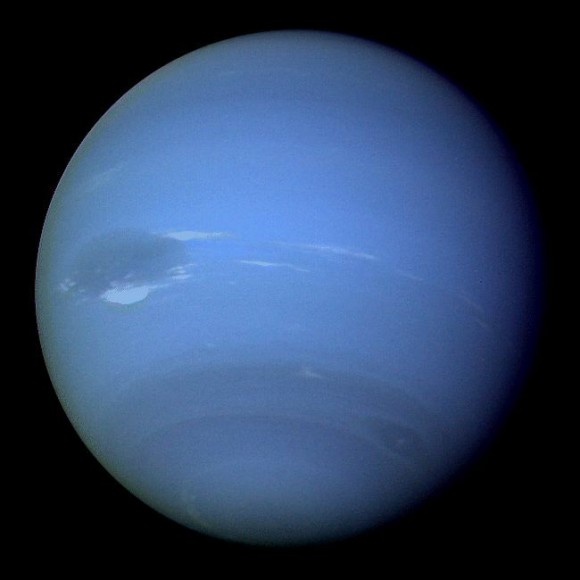

Neptune is the eight planet of our Solar System, and the farthest from the Sun. Like Uranus, it is both a gas giant and ice giant, composed of a solid core surrounded by methane and ammonia ices, surrounded by large amounts of methane gas. Once again, this methane is what gives the planet its blue color. It is also the smallest gas giant in the outer Solar System, and the fourth largest planet.

All of the gas giants have intense storms, but Neptune has the fastest winds of any planet in our Solar System. The winds on Neptune can reach up to 2,100 kilometers per hour, and the strongest of which are believed to be the Great Dark Spot, which was seen in 1989, or the Small Dark Spot (also seen in 1989). In both cases, these storms and the planet itself were observed by the Voyager 2 spacecraft, the only one to capture images of the planet.

Universe Today has many interesting articles on the subject of the planets, such as interesting facts about the planets and interesting facts about the Solar System.

If you are looking for more information, try NASA’s Solar System exploration page and an overview of the Solar System.

Astronomy Cast has episodes on all of the planets including Mercury.