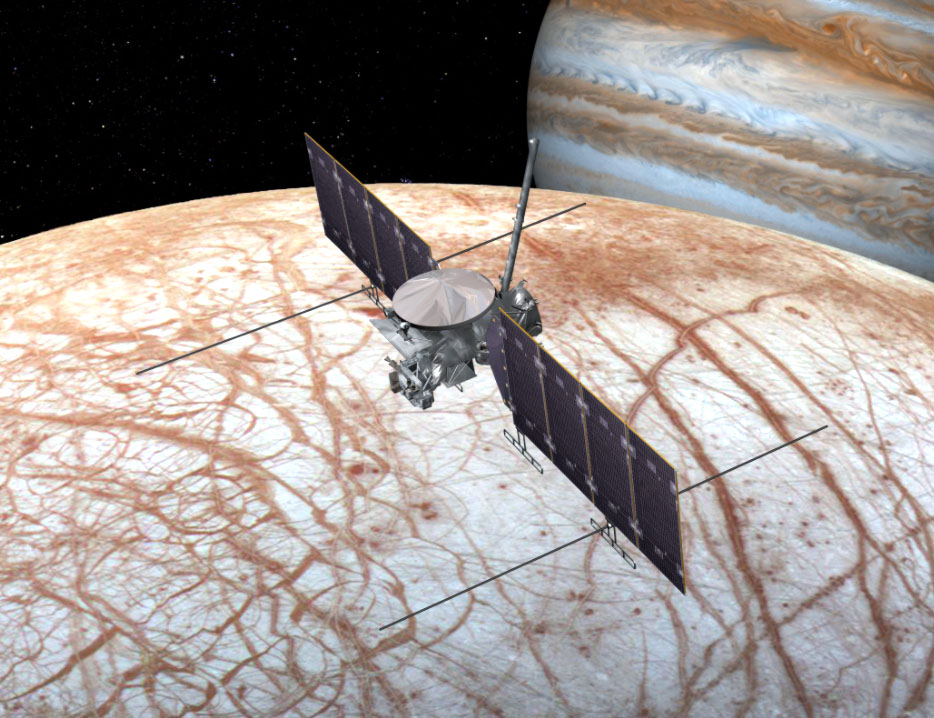

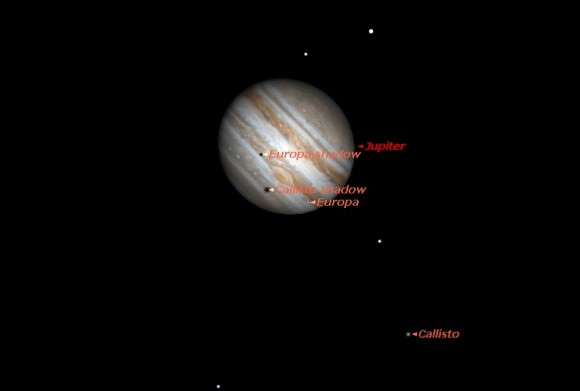

NASA’s Galileo spacecraft arrived at Jupiter on December 7, 1995, and proceeded to study the giant planet for almost 8 years. It sent back a tremendous amount of scientific information that revolutionized our understanding of the Jovian system. By the end of its mission, Galileo was worn down. Instruments were failing and scientists were worried they wouldn’t be able to communicate with the spacecraft in the future. If they lost contact, Galileo would continue to orbit the Jupiter and potentially crash into one of its icy moons.

Galileo would certainly have Earth bacteria on board, which might contaminate the pristine environments of the Jovian moons, and so NASA decided it would be best to crash Galileo into Jupiter, removing the risk entirely. Although everyone in the scientific community were certain this was the safe and wise thing to do, there were a small group of people concerned that crashing Galileo into Jupiter, with its Plutonium thermal reactor, might cause a cascade reaction that would ignite Jupiter into a second star in the Solar System.

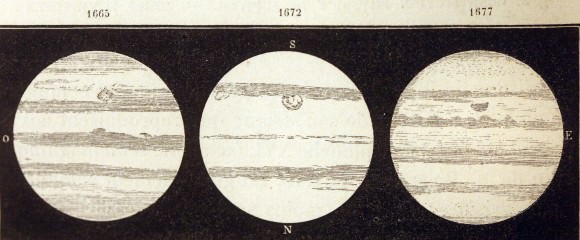

Hydrogen bombs are ignited by detonating plutonium, and Jupiter’s got a lot of hydrogen.Since we don’t have a second star, you’ll be glad to know this didn’t happen. Could it have happened? Could it ever happen? The answer, of course, is a series of nos. No, it couldn’t have happened. There’s no way it could ever happen… or is there?

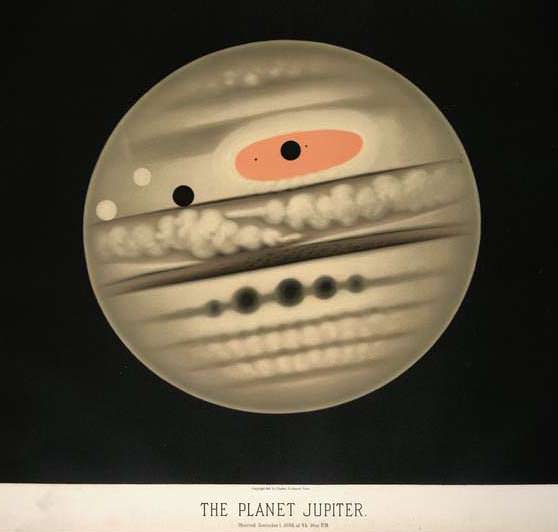

Jupiter is mostly made of hydrogen, in order to turn it into a giant fireball you’d need oxygen to burn it. Water tells us what the recipe is. There are two atoms of hydrogen to one atom of oxygen. If you can get the two elements together in those quantities, you get water.

In other words, if you could surround Jupiter with half again more Jupiter’s worth of oxygen, you’d get a Jupiter plus a half sized fireball. It would turn into water and release energy. But that much oxygen isn’t handy, and even though it’s a giant ball of fire, that’s still not a star anyway. In fact, stars aren’t “burning” at all, at least, not in the combustion sense.

Our Sun produces its energy through fusion. The vast gravity compresses hydrogen down to the point that high pressure and temperatures cram hydrogen atoms into helium. This is a fusion reaction. It generates excess energy, and so the Sun is bright. And the only way you can get a reaction like this is when you bring together a massive amount of hydrogen. In fact… you’d need a star’s worth of hydrogen. Jupiter is a thousand times less massive than the Sun. One thousand times less massive. In other words, if you crashed 1000 Jupiters together, then we’d have a second actual Sun in our Solar System.

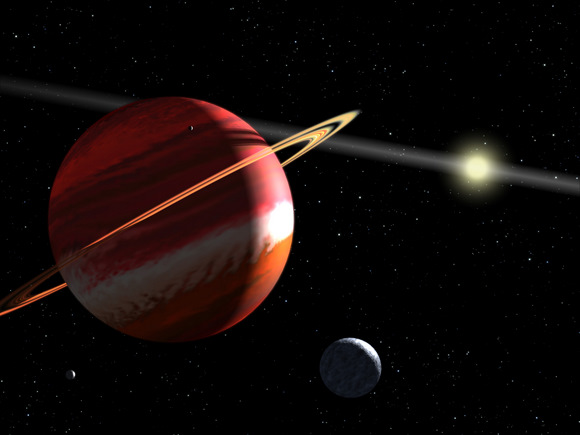

But the Sun isn’t the smallest possible star you can have. In fact, if you have about 7.5% the mass of the Sun’s worth of hydrogen collected together, you’ll get a red dwarf star. So the smallest red dwarf star is still about 80 times the mass of Jupiter. You know the drill, find 79 more Jupiters, crash them into Jupiter, and we’d have a second star in the Solar System.

There’s another object that’s less massive than a red dwarf, but it’s still sort of star like: a brown dwarf. This is an object which isn’t massive enough to ignite in true fusion, but it’s still massive enough that deuterium, a variant of hydrogen, will fuse. You can get a brown dwarf with only 13 times the mass of Jupiter. Now that’s not so hard, right? Find 13 more Jupiters, crash them into the planet?

As was demonstrated with Galileo, igniting Jupiter or its hydrogen is not a simple matter.

We won’t get a second star unless there’s a series of catastrophic collisions in the Solar System.

And if that happens… we’ll have other problems on our hands.