[/caption]

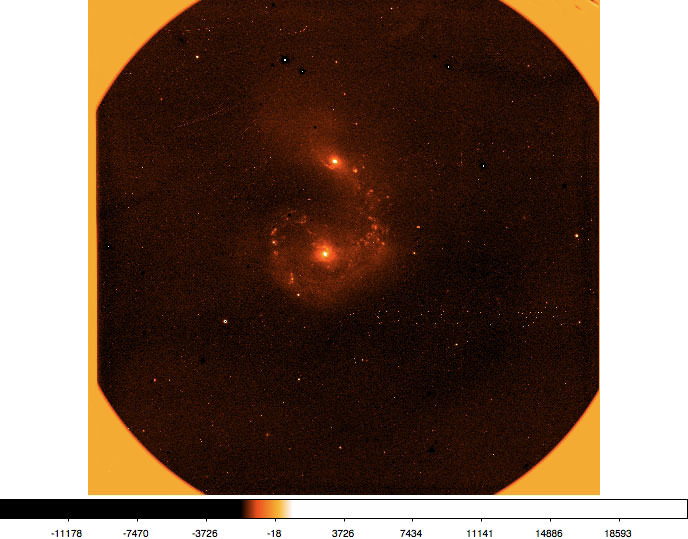

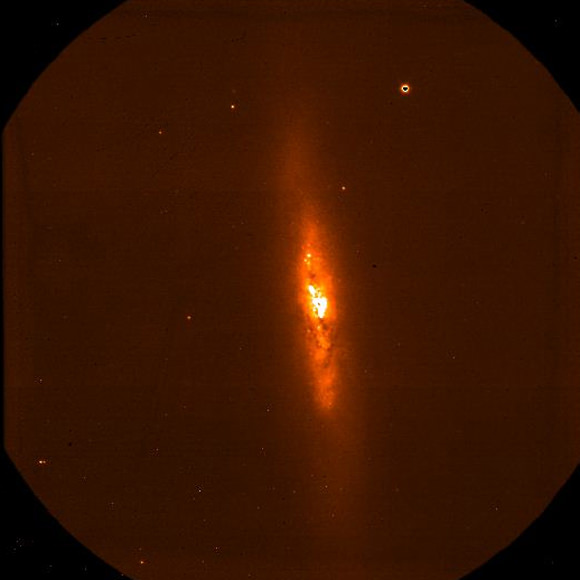

Last week, on April 4, 2012, the W.M. Keck Observatory’s brand-new MOSFIRE instrument opened its infrared-sensing eyes to the Universe for the first time, capturing the image above of a pair of interacting galaxies known as The Antennae. Once fully commissioned and scientific observations begin, MOSFIRE will greatly enhance the imaging abilities of “the world’s most productive ground-based observatory.”

Installed into the Keck I observatory, MOSFIRE — which stands for Multi-Object Spectrometer For Infra-Red Exploration — is able to gather light in infrared wavelengths. This realm of electromagnetic radiation lies just beyond red on the visible spectrum (the “rainbow” of light that our eyes are sensitive to) and is created by anything that emits heat. By “seeing” in infrared, MOSFIRE can peer through clouds of otherwise opaque dust and gas to observe what lies beyond — such as the enormous black hole that resides at the center of our galaxy.

MOSFIRE can also resolve some of the most distant objects in the Universe, in effect looking back in time toward the period “only” a half-billion years after the Big Bang. Because light from that far back has been so strongly shifted into the infrared due to the accelerated expansion of the Universe (a process called redshift) only instruments like MOSFIRE can detect it.

The instrument itself must be kept at a chilly -243ºF (-153ºC) in order to not contaminate observations with its own heat.

(Watch the installation of the MOSFIRE instrument here.)

Astronomers also plan to use MOSFIRE to search for brown dwarfs — relatively cool objects that never really gained enough mass to ignite fusion in their cores. Difficult to image even in infrared, it’s suspected that our own galaxy is teeming with them.

The impressive new instrument has the ability to survey up to 46 objects at once and then do a quick-change to new targets in just minutes, as opposed to the one to two days it can typically take other telescopes!

Images taken on the nights of April 4 and 5 are just the beginning of what promises to be a new heat-seeking era for the Mauna Kea-based observatory!

“The MOSFIRE project team members at Keck Observatory, Caltech, UCLA, and UC Santa Cruz are to be congratulated, as are the observatory operations staff who worked hard to get MOSFIRE integrated into the Keck I telescope and infrastructure,” says Bob Goodrich, Keck Observatory Observing Support Manager. “A lot of people have put in long hours getting ready for this momentous First Light.”

Read more on the Keck press release here.

The W. M. Keck Observatory operates two 10-meter optical/infrared telescopes on the summit of Mauna Kea on the Big Island of Hawaii. The spectrometer was made possible through funding provided by the National Science Foundation and astronomy benefactors Gordon and Betty Moore.