What is it like to make contact with a 36-year old dormant spacecraft?

“The intellectual side of you systematically goes through all the procedures but you really end up doing a happy dance when it actually works,” Keith Cowing told Universe Today. Cowing, most notably from NASA Watch.com, and businessman Dennis Wingo are leading a group of volunteer engineers that are attempting to reboot the International Sun-Earth Explorer (ISEE-3) spacecraft after it has traveled 25 billion kilometers around the Solar System the past 30 years.

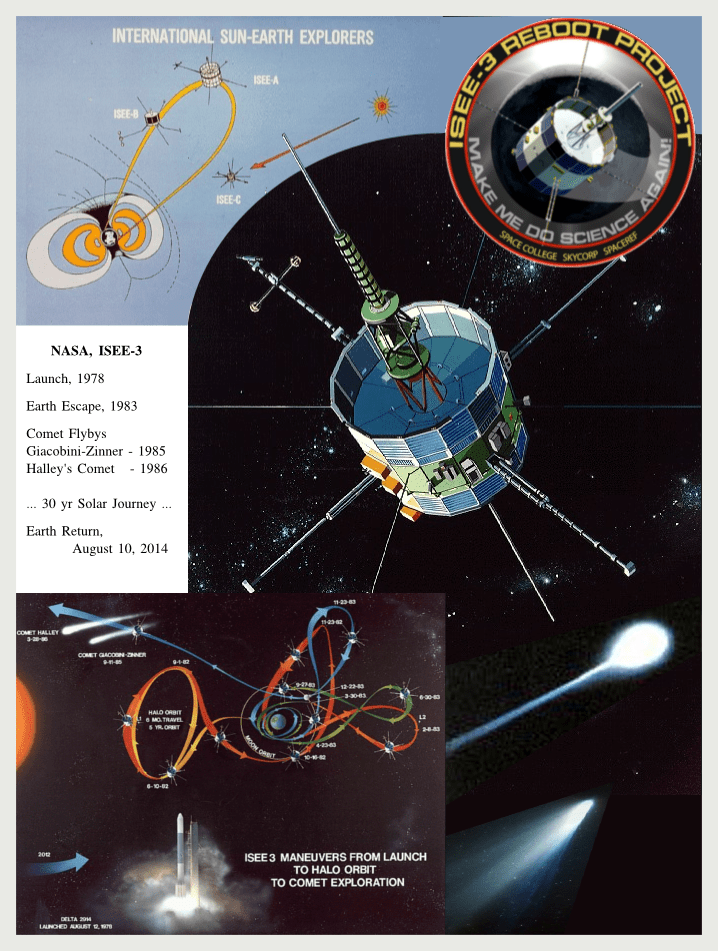

Its initial mission launched in 1978 to study Earth’s magnetosphere, and the spacecraft was later repurposed to study two comets. Now, on its final leg of a 30-plus year journey and heading back to the vicinity of Earth, the crowdfunding effort ISEE-3 Reboot has been working to reactivate the hibernating spacecraft since NASA wasn’t able to provide any funds to do so.

More Details: No turning back, NASA ISEE-3 Spacecraft Returning to Earth after a 36 Year Journey

The team awakened the spacecraft by communicating from the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico, using a donated transmitter. While most of the team has been in Puerto Rico, Cowing is back at home in the US manning the surge of media attention this unusual mission has brought.

@ISEE3Reboot More #ISEE3 post-First Contact pictures, inc. Dana & Phil from AO. @_jmalsbury from afar (& @bistromath) pic.twitter.com/j3XxVcckqy

— Balint Seeber (@spenchdotnet) June 2, 2014

Those at Arecibo are now methodically going through all the systems, figuring out what the spacecraft can and can’t do.

“We did determine the spin rate of spacecraft is slightly below what it should be,” Cowing said, “but the point there is that we’re now understanding the telemetry that we’re getting and its coming back crystal clear.”

For you tech-minded folks, the team determined the spacecraft is spinning at 19.16 rpm. “The mission specification is 19.75 +/- 0.2 rpm. We have also learned that the spacecraft’s attitude relative to the ecliptic is 90.71 degrees – the specification is 90 +/- 1.5 degrees. In addition, we are now receiving information from the spacecraft’s magnetometer,” Cowing wrote in an update on the website.

The next task will be looking at the propulsion system and making sure they can actually fire the engines for a trajectory correction maneuver (TCM), currently targeted for June 17.

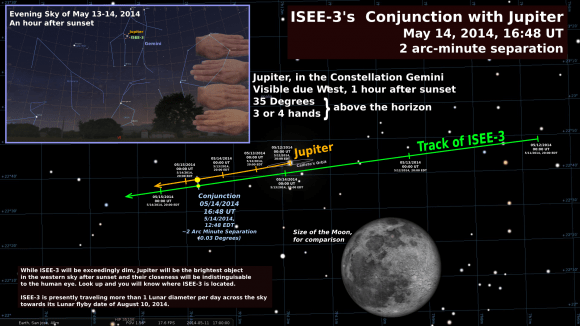

One thing this TCM will do is to make sure the spacecraft doesn’t hit the Moon. Initial interactions with the ISEE-3 from Arecibo showed the spacecraft was not where the JPL ephemeris predicted it was going to be.

“That’s a bit troublesome because if you look at the error bars, it could hit Moon, or even the Earth, which is not good,” Cowing said, adding that they’ve since been able to refine the trajectory and found the ephemeris was not off as much as initially thought, and so such an impact is quite unlikely.

“However, it’s not been totally ruled out, — as NASA would say it’s a not a non-zero chance,” Cowing said. “The fact that it was not where it was supposed to be shows there were changes in its position. But assuming we can fire the engines when we want to, it shouldn’t be a problem. As it stands now, if we didn’t do anything, the chance of it hitting the Moon is not zero. But it’s not that likely.”

But the fact that the predicted location of the spacecraft is only off by less than 30,000 km is actually pretty amazing.

Dennis Wingo wrote this on the team’s website:

Consider this, the spacecraft has completed almost 27 orbits of the sun since the last trajectory maneuver. That is 24.87 billion kilometers. They are off course by less than 30,000 km. I can’t even come up with an analogy to how darn good that is!! That is almost 1 part in ten million accuracy! We need to confirm this with a DSN ranging, but if this holds, the fuel needed to accomplish the trajectory change is only about 5.8 meters/sec, or less than 10% of what we thought last week!

We truly stand on the shoulders of steely eyed missile men giants..

In 1982, NASA engineers at Goddard Space Flight Center, led by Robert Farquhar devised the maneuvers needed to send the spacecraft ISEE-3 out of the Earth-Moon system. It was renamed the International Cometary Explorer (ICE) to rendezvous with two comets – Giacobini-Zinner in 1985 and Comet Halley in 1986.

“Bob Farquhar and his team initially did it with pencils on the back of envelopes,” Cowing said, “so it is pretty amazing. And we’re really happy with the trajectory because we’ll need less fuel – we have 150 meters per second of fuel available, and we’ll only need about 6 meters per second of maneuvering, so that will give us a lot of margin to do the other things in terms of the final orbit, so we’re happy with that. But we have to fire the engines first before we pat ourselves on the back.”

And that’s where the biggest challenge of this amateur endeavor lies.

“The biggest challenge will be getting the engines to fire,” Cowing said. “The party’s over if we can’t get it to do that. The rest will be gravy. So that’s what we’re focusing on now.”

After the June 17 TCM, the next big date is August 10, when the team will attempt to put the spacecraft in Earth orbit and then resume its original mission that began back in 1978 – all made possible by volunteers and crowdfunding.

We’ll keep you posted on this effort, but follow the ISEE-3 Reboot Twitter feed, which is updated frequently and immediately after anything happens with the spacecraft. Also, for more detailed updates, check out the SpaceCollege website.