When you sit back and think about how far away exoplanets are — and how faint — it’s a scientific feat that we can find these distant worlds outside our Solar System at all. It’s even harder to learn about the world if the exoplanet is orbiting a dim star — say, about two-thirds the size of the Sun — that is faint through even the largest telescope.

In response to this problem, there’s one science team that thinks it’s found a way to solve it. Their research bumped a planet from the habitable zone to the not-so-friendly zone of a star. Here’s how it happened:

The usual way to measure a distant star is this: look at the light. A Sun-sized star, for example, would have its light waves measured at different wavelengths. Scientists then match what they see to spectra (light bands) that are created artificially.

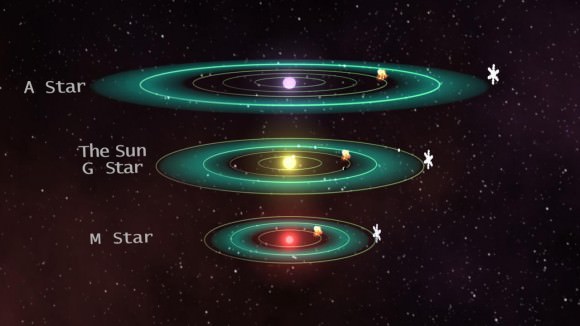

This method doesn’t work so well for smaller stars, though. “The challenge is that small stars are incredibly difficult to characterize,” stated Sarah Ballard, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Washington, in a press release. Worse, these small guys make up about two-thirds of the stars in the universe.

Ballard led a multi-university team describing a “characterization by proxy” method accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal and now available online.

The science team based their work on previous research performed by astronomer Tabetha Boyajian, who is currently at Yale University.

Boyajian combined the resources of several telescopes that measured wavelengths of light, wavelengths that are slightly longer than visible light. This technique allowed the interferometer (the combined telescopes) to figure out the size of stars that are close by.

With that data on hand, Ballard and her colleagues looked out into the universe. Their target was Kepler-61b (Kepler Object 1361.01), a “candidate” planet about double the size of Earth spotted by the planet-hunting Kepler space telescope. The candidate, if proven, is orbiting a low-mass star 900 light-years away that is hard to measure in a telescope.

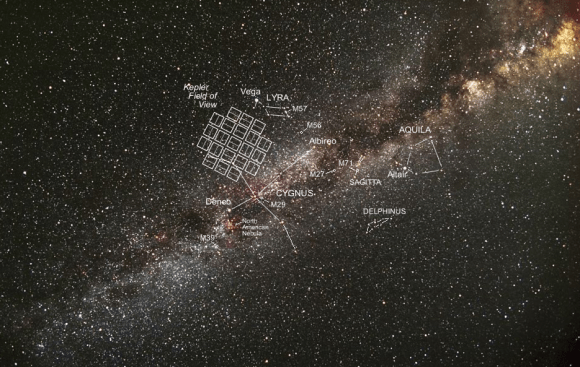

Next, the scientists picked four nearby stars that have similar light patterns, reasoning that they would be spectroscopially close enough to Kepler-61b’s parent star to make accurate measurements. The four stars are located in Ursa Major and Cygnus, ranging between 12 to 25 light years away from Earth.

When the scientists compared the measurements to Kepler 61’s star, a surprise emerged.

“Kepler-61 turned out to be bigger and hotter than expected,” the University of Washington stated. “This in turn recalibrated planet Kepler-61b’s relative size upward as well — meaning it, too, would be hotter than previously thought and no longer a resident of the star’s habitable zone.”

The newly refined planetary radius for Kepler-61b is 2.15 times the radius of Earth (plus or minus 0.13 radii). Astronomers estimate it orbits its star about once every 59.9 days and has a temperature of 273 Kelvin (plus or minus 13 Kelvin.)

Just to wrap up, here’s a note about how likely it is that Kepler-61b is actually a planet — and not a planetary candidate.

The candidate was first described in this 2011 scientific paper. Kepler-61b is just one in a long list of 1,235 planetary candidates catalogued in that paper, all discovered in just four months — between May 2 and Sept. 16, 2009.

While the NASA Exoplanet Archive still lists Kepler-61b as a candidate planet — one that must be confirmed by independent observations — this 2011 paper says that most Kepler candidates have a strong possibility of being actual planets because the Kepler software is technologically apt.

In other words, Ballard and her co-authors write in the research, Kepler-61b is very likely to be a planet itself — with only 4.8 percent possibility of being a “false positive”, to be exact.

Source: University of Washington