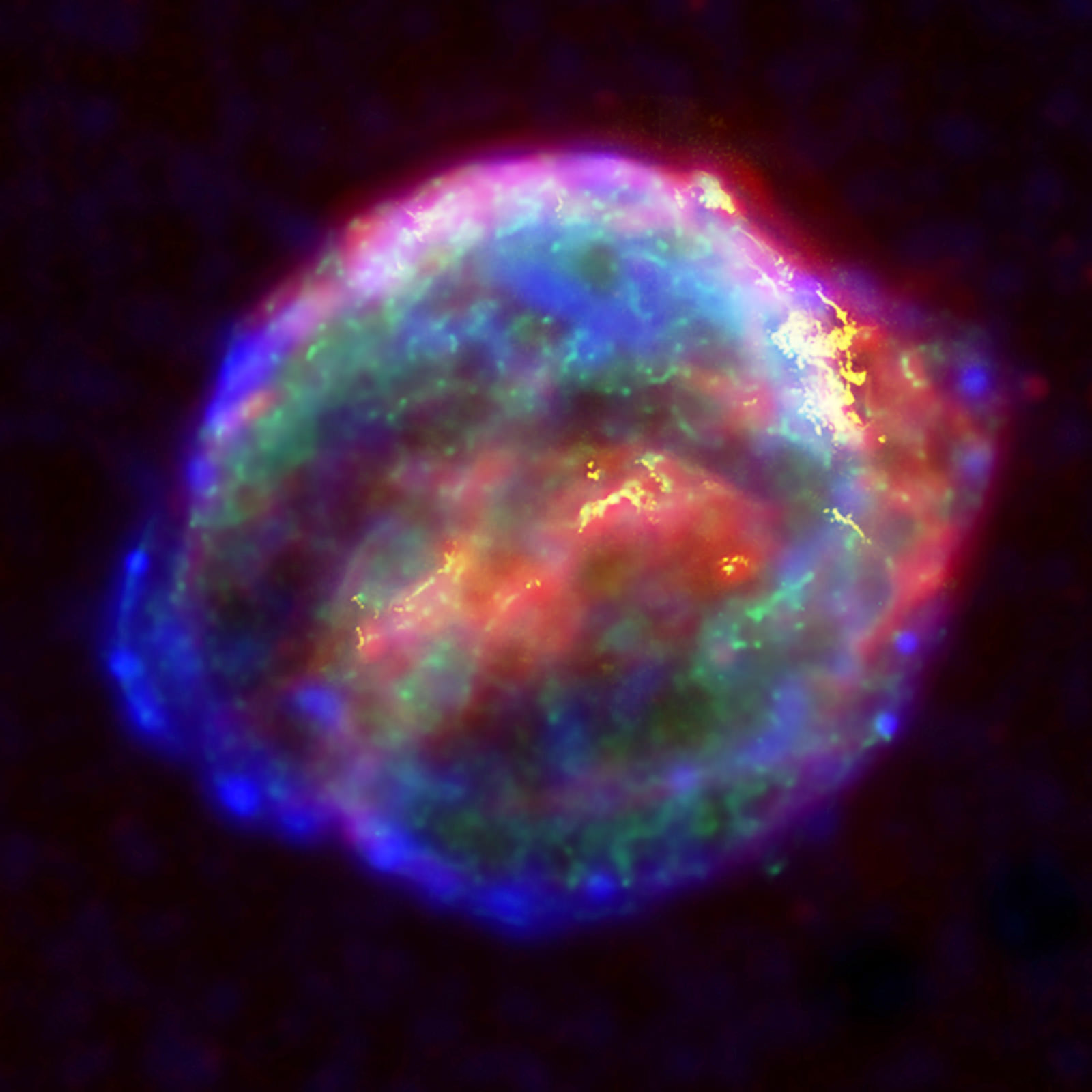

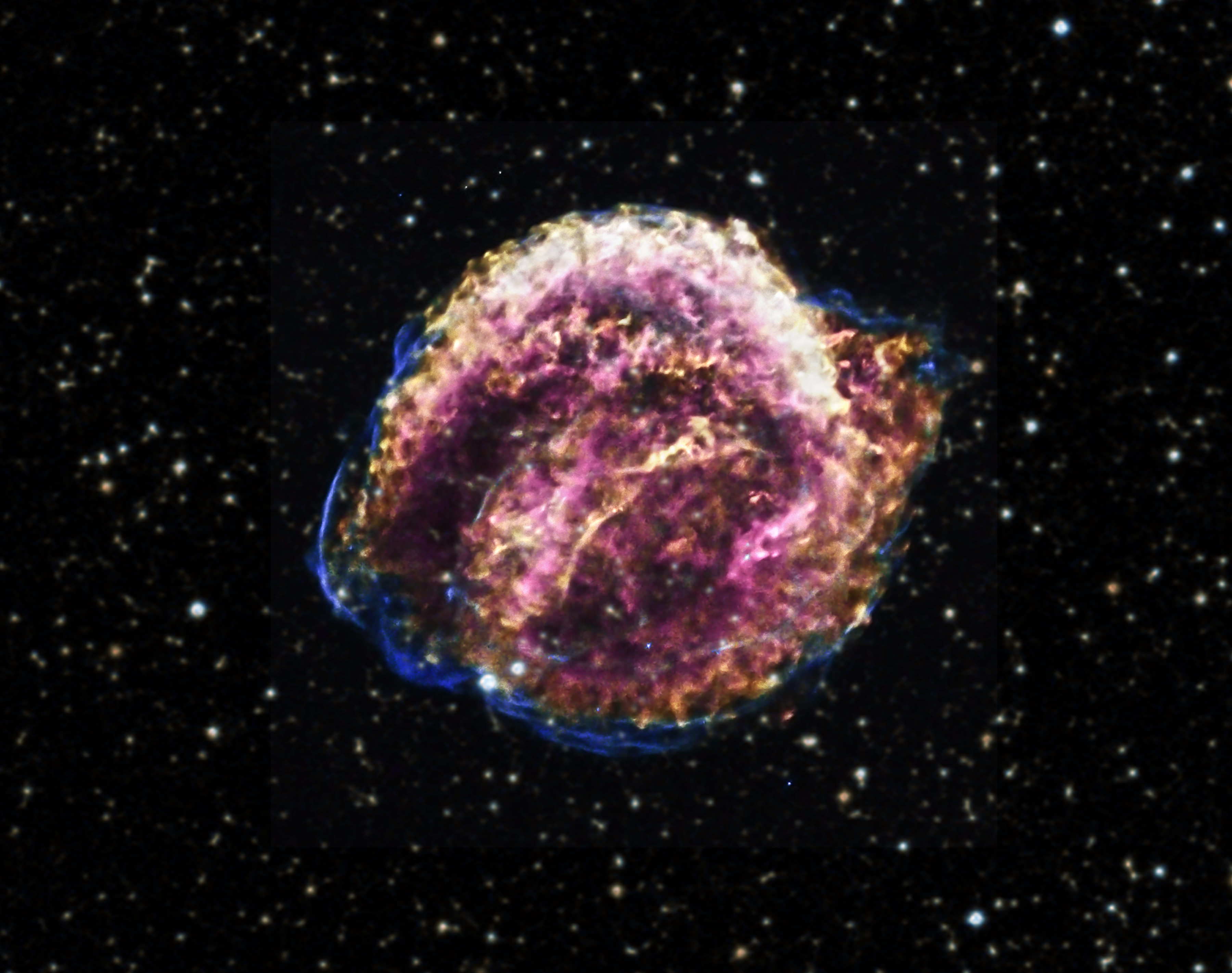

A composite image of Chandra X-ray data shows a rainbow of reds, yellows, green, blue and purple, from lower to higher energies. Optical data from the Digitized Sky Survey, shown in pale yellow and blue, offer a starry background for the image. Optical: DSS

An arc of hot gas that spewed from the Kepler Supernova offers tantalizing clues that the cataclysmic stellar explosion of 1604 was not only more powerful than previously thought but also farther away according to a recent study using Chandra X-ray Observatory data published in the September 1, 2012 edition of The Astrophysical Journal.

A new star appeared in the autumn skies of 1604. Although it was described by other astronomers, it was famous astronomer Johannes Kepler who thoroughly detailed the the second supernova sighting in a generation. The star shined more brilliant than Jupiter and remained visible – even during the day – over several weeks.

Look for Kepler’s Supernova at the foot of the constellation Ophiuchus, the Serpent Bearer, in visible light and you won’t see much. But the hot gas and dust glow brightly in the X-ray images from Chandra. Astronomers have long puzzled over Kepler’s Supernova. Astronomers now know the explosion that created the remnant was a Type Ia supernova. Supernovae of this class occur when a white dwarf, the white-hot dead core of a once Sun-like star, gains mass by either merging with another white dwarf or drawing gas onto its surface from a larger companion star until temperatures soar and thermonuclear processes spiral out of control resulting in a detonation that destroys the star.

Kepler’s Supernova is a bit different because the expanding debris cloud is shaped by gas and dust clouds throughout the area. Most Type Ia supernovae are symmetrical; nearly perfect expanding bubbles of material. A quick look at the Chandra image of the supernova and one notices the bright arc of material across the top edge of shockwave. In one model, a pre-supernova white dwarf and its companion were moving through a nebulous area creating a bow shock, like a boat plowing through water, in front. Another model suggests that the glowing arc is the edge of the supernova shockwave as it passes through an area of increasingly dense gas and dust. Both models push the distance of the supernova from the previously believed 13,000 light-years to more than 20,000 light-years from Earth, scientists say in the paper.

Scientists also found large amounts of iron by looking at the X-ray light from Chandra meaning that the explosion was far more powerful than an average Type Ia supernova. Astronomers have observed a similar Type Ia supernova using Chandra and an optical telescope in the Large Magellanic Cloud.

Kepler’s Supernova is the last Milky Way supernova visible to the naked eye. It was the second supernova to be observed in that generation after SN 1572 in Cassiopeia studied by the famous astronomer Tycho Brahe.

Source: http://chandra.harvard.edu

About the author: John Williams is owner of TerraZoom, a Colorado-based web development shop specializing in web mapping and online image zooms. He also writes the award-winning blog, StarryCritters, an interactive site devoted to looking at images from NASA’s Great Observatories and other sources in a different way. A former contributing editor for Final Frontier, his work has appeared in the Planetary Society Blog, Air & Space Smithsonian, Astronomy, Earth, MX Developer’s Journal, The Kansas City Star and many other newspapers and magazines. Follow John on Twitter @terrazoom.