In the 18th century, observations made of all the known planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn) led astronomers to discern a pattern in their orbits. Eventually, this led to the Titius–Bode law, which predicted the amount of space between the planets. In accordance with this law, there appeared to be a discernible gap between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, and investigation into it led to a major discovery.

Eventually, astronomers realized that this region was pervaded by countless smaller bodies which they named “asteroids”. This in turn led to the term “Asteroid Belt”, which has since entered into common usage. Like all the planets in our Solar System, it orbits our Sun, and has played an important role in the evolution and history of our Solar System.

Structure and Composition:

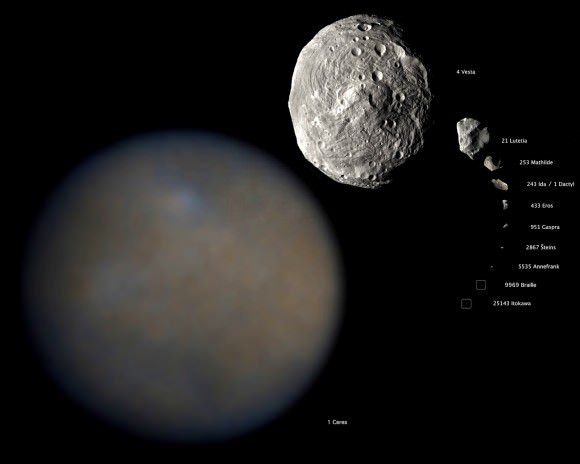

The Asteroid Belt consists of several large bodies, along with millions of smaller size. The larger bodies, such as Ceres, Vesta, Pallas, and Hygiea, account for half of the belt’s total mass, with almost one-third accounted for by Ceres alone. Beyond that, over 200 asteroids that are larger than 100 km in diameter, and 0.7–1.7 million asteroids with a diameter of 1 km or more.

Despite the impressive number of objects contained within the belt, the Main Belt’s asteroids are also spread over a very large volume of space. As a result, the average distance between objects is roughly 965,600 km (600,000 miles), meaning that the Main Belt consists largely of empty space. In fact, due to the low density of materials within the Belt, the odds of a probe running into an asteroid are now estimated at less than one in a billion.

The main (or core) population of the asteroid belt is sometimes divided into three zones, which are based on what is known as “Kirkwood gaps”. Named after Daniel Kirkwood, who announced in 1866 the discovery of gaps in the distance of asteroids, these gaps are similar to what is seen with Saturn’s and other gas giants’ systems of rings.

Origin:

Originally, the Asteroid Belt was thought to be the remnants of a much larger planet that occupied the region between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. This theory was originally suggested by Heinrich Olbders to William Herschel as a possible explanation for the existence of Ceres and Pallas. However, this hypothesis has since been shown to have several flaws.

For one, the amount of energy required to destroy a planet would have been staggering, and no scenario has been suggested that could account for such events. Second, there is the fact that the mass of the Asteroid Belt is only 4% that of the Moon (and 22% that of Pluto). The odds of a cataclysmic collision with such a tiny body are very unlikely. Lastly, the significant chemical differences between the asteroids do no point towards a common origin.

Today, the scientific consensus is that, rather than fragmenting from an original planet, the asteroids are remnants from the early Solar System that never formed a planet at all. During the first few million years of the Solar System’s history, gravitational accretion caused clumps of matter to form out of an accretion disc. These clumps gradually came together, eventually undergoing hydrostatic equilibrium (become spherical) and forming planets.

However, within the region of the Asteroid Belt, planestesimals were too strongly perturbed by Jupiter’s gravity to form a planet. As such, these objects would continue to orbit the Sun as they had before, with only one object (Ceres) having accumulated enough mass to undergo hydrostatic equilibrium. On occasion, they would collide to produce smaller fragments and dust.

The asteroids also melted to some degree during this time, allowing elements within them to be partially or completely differentiated by mass. However, this period would have been necessarily brief due to their relatively small size. It likely ended about 4.5 billion years ago, a few tens of millions of years after the Solar System’s formation.

Though they are dated to the early history of the Solar System, the asteroids (as they are today) are not samples of its primordial self. They have undergone considerable evolution since their formation, including internal heating, surface melting from impacts, space weathering from radiation, and bombardment by micrometeorites. Hence, the Asteroid Belt today is believed to contain only a small fraction of the mass of the primordial belt.

Computer simulations suggest that the original asteroid belt may have contained mass equivalent to the Earth. Primarily because of gravitational perturbations, most of the material was ejected from the belt a million years after its formation, leaving behind less than 0.1% of the original mass. Since then, the size distribution of the asteroid belt is believed to have remained relatively stable.

When the asteroid belt was first formed, the temperatures at a distance of 2.7 AU from the Sun formed a “snow line” below the freezing point of water. Essentially, planetesimals formed beyond this radius were able to accumulate ice, some of which may have provided a water source of Earth’s oceans (even more so than comets).

Distance from the Sun:

Located between Mars and Jupiter, the belt ranges in distance between 2.2 and 3.2 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun – 329 million to 478.7 million km (204.43 million to 297.45 million mi). It is also an estimated to be 1 AU thick (149.6 million km, or 93 million mi), meaning that it occupies the same amount of distance as what lies between the Earth to the Sun.

The distance of an asteroid from the Sun (its semi-major axis) depends upon its distribution into one of three different zones based on the Belt’s “Kirkwood Gaps”. Zone I lies between the 4:1 resonance and 3:1 resonance Kirkwood gaps, which are roughly 2.06 and 2.5 AUs (3 to 3.74 billion km; 1.86 to 2.3 billion mi) from the Sun, respectively.

Zone II continues from the end of Zone I out to the 5:2 resonance gap, which is 2.82 AU (4.22 billion km; 2.6 mi) from the Sun. Zone III, the outermost section of the Belt, extends from the outer edge of Zone II to the 2:1 resonance gap, located some 3.28 AU (4.9 billion km; 3 billion mi) from the Sun.

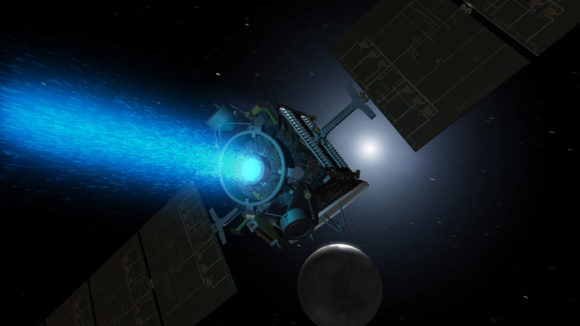

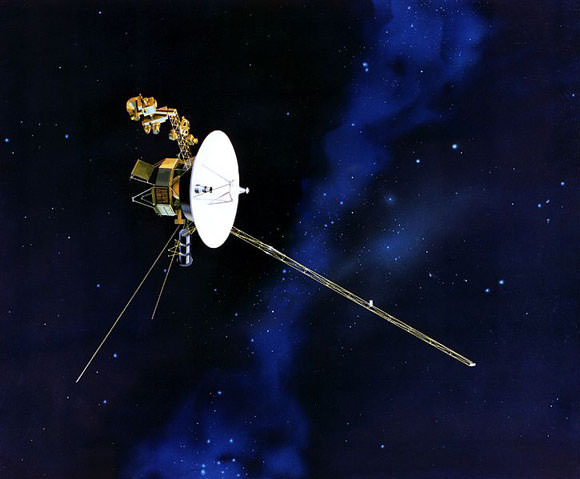

While many spacecraft have been to the Asteroid Belt, most were passing through on their way to the outer Solar System. Only in recent years, with the Dawn mission, that the Asteroid Belt has been a focal point of scientific research. In the coming decades, we may find ourselves sending spaceships there to mine asteroids, harvest minerals and ices for use here on Earth.

We’ve written many articles about the Asteroid Belt here at Universe Today. Here’s What is the Asteroid Belt?, How Long Does it Take to get to the Asteroid Belt?, How Far is the Asteroid Belt from Earth?, Why Isn’t the Asteroid Belt a Planet?, and Why the Asteroid Belt Doesn’t Threaten Spacecraft.

To learn more, check out NASA’s Lunar and Planetary Science Page on asteroids, and the Hubblesite’s News Releases about Asteroids.

Astronomy Cast also some interesting episodes about asteroids, like Episode 55: The Asteroid Belt and Episode 29: Asteroids Make Bad Neighbors.

Sources: