[/caption]

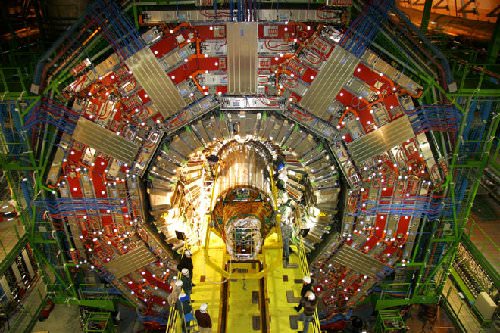

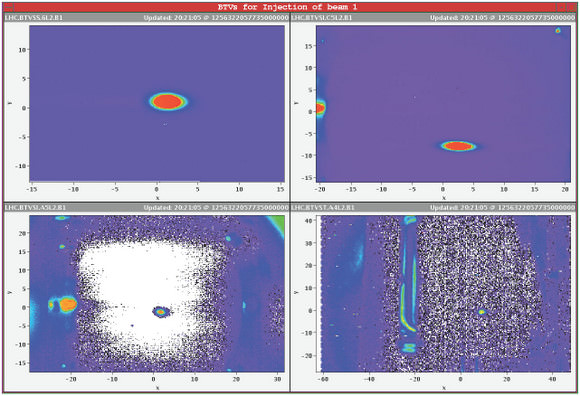

Surprisingly, rumors still persist in some corners of the Internet that the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is going to destroy the Earth – even though nearly three years have passed since it was first turned on. This may be because it is yet to be ramped up to full power in 2014 – although it seems more likely that this is just a case of moving the goal posts, since the same doomsayers were initially adamant that the Earth would be destroyed the moment the LHC was switched on, in September 2008.

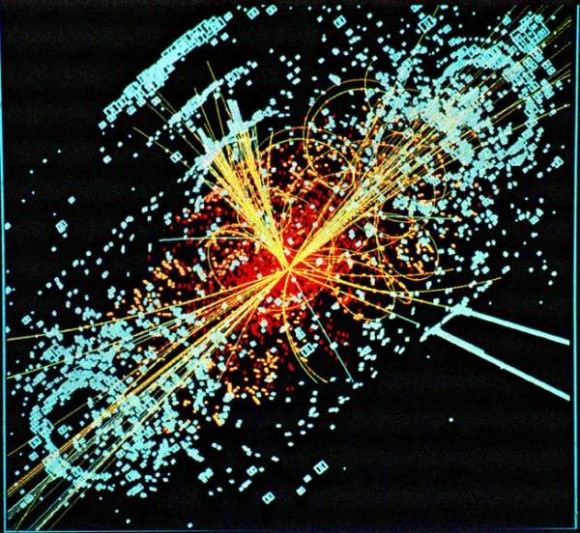

The story goes that the very high energy collisions engineered by the LHC could jam colliding particles together with such force that their mass would be compressed into a volume less than the Schwarzschild radius required for that mass. In other words, a microscopic black hole would form and then grow in size as it sucked in more matter, until it eventually consumed the Earth.

Here’s a brief run-through of why this can’t happen.

1. Microscopic black holes are implausible.

While a teaspoon of neutron star material might weigh several million tons, if you extract a teaspoon of neutron star material from a neutron star it will immediately blow out into the volume you might expect several million tons of mass to usually occupy.

Notwithstanding you can’t physically extract a teaspoon of black hole material from a black hole – if you could, it is reasonable to expect that it would also instantly expand. You can’t maintain these extreme matter densities outside of a region of extreme gravitational compression that is created by the proper mass of a stellar-scale object.

The hypothetical physics that might allow for the creation of microscopic black holes (large extra dimensions) proposes that gravity gains more force in near-Planck scale dimensions. There is no hard evidence to support this theory – indeed there is a growing level of disconfirming evidence arising from various sources, including the LHC.

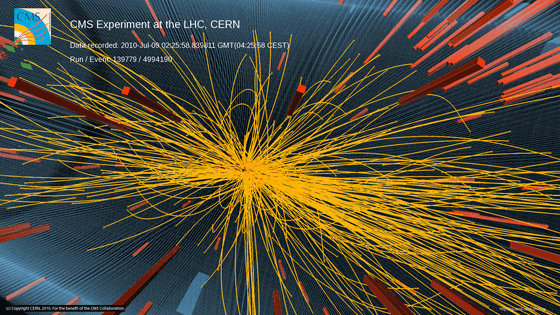

High energy particle collisions involve converting momentum energy into heat energy, as well as overcoming the electromagnetic repulsion that normally prevents charged particles from colliding. But the heat energy produced quickly dissipates and the collided particles fragment into sub-atomic shrapnel, rather than fusing together. Particle colliders attempt to mimic conditions similar to the Big Bang, not the insides of massive stars.

2. A hypothetical microscopic black hole couldn’t devour the Earth anyway.

Although whatever goes on inside the event horizon of a black hole is a bit mysterious and unknowable – physics still operates in a conventional fashion outside. The gravitational influence exerted by the mass of a black hole falls away by the inverse square of the distance from it, just like it does for any other celestial body.

The gravitational influence exerted by a microscopic black hole composed of, let’s say 1000 hyper-compressed protons, would be laughably small from a distance of more than its Schwarzschild radius (maybe 10-18 metres). And it would be unable to consume more matter unless it could overcome the forces that hold other matter together – remembering that in quantum physics, gravity is the weakest force.

It’s been calculated that if the Earth had the density of solid iron, a hypothetical microscopic black hole in linear motion would be unlikely to encounter an atomic nucleus more than once every 200 kilometres – and if it did, it would encounter a nucleus that would be at least 1,000 times larger in diameter.

So the black hole couldn’t hope to swallow the whole nucleus in one go and, at best, it might chomp a bit off the nucleus in passing – somehow overcoming the strong nuclear force in so doing. The microscopic black hole might have 100 such encounters before its momentum carried it all the way through the Earth and out the other side, at which point it would probably still be a good order of magnitude smaller in size than an uncompressed proton.

And that still leaves the key issue of charge out of the picture. If you could jam multiple positively-charged protons together into such a tiny volume, the resultant object should explode, since the electromagnetic force far outweighs the gravitational force at this scale. You might get around this if an exactly equivalent number of electrons were also added in, but this requires appealing to an implausible level of fine-tuning.

3. What the doomsayers say

When challenged with the standard argument that higher-than-LHC energy collisions occur naturally and frequently as cosmic ray particles collide with Earth’s upper atmosphere, LHC conspiracy theorists refer to the high school physics lesson that two cars colliding head-on is a more energetic event than one car colliding with a brick wall. This is true, to the extent that the two car collision has twice the kinetic energy as the one car collision. However, cosmic ray collisions with the atmosphere have been measured as having 50 times the energy that will ever be generated by LHC collisions.

In response to the argument that a microscopic black hole would pass through the Earth before it could achieve any appreciable mass gain, LHC conspiracy theorists propose that an LHC collision would bring the combined particles to a dead stop and they would then fall passively towards the centre of the Earth with insufficient momentum to carry them out the other side.

This is also implausible. The slightest degree of transverse momentum imparted to LHC collision fragments after a head-on collision of two particles travelling at nearly 300,000 kilometres a second will easily give those fragments an escape velocity from the Earth (which is only 11.2 kilometres a second, at sea-level).

Further reading: CERN The safety of the LHC.