Gravitational-wave astronomy is still in its infancy. LIGO and other observatories have opened a new window on the universe, but their gravitational view of the cosmos is limited. To widen our view, we have the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves (NANOGrav).

Continue reading “Astronomers see a Hint of the Gravitational Wave Background to the Universe”Next Generation Gravitational Wave Detectors Should be Able to see the Primordial Waves From the Big Bang

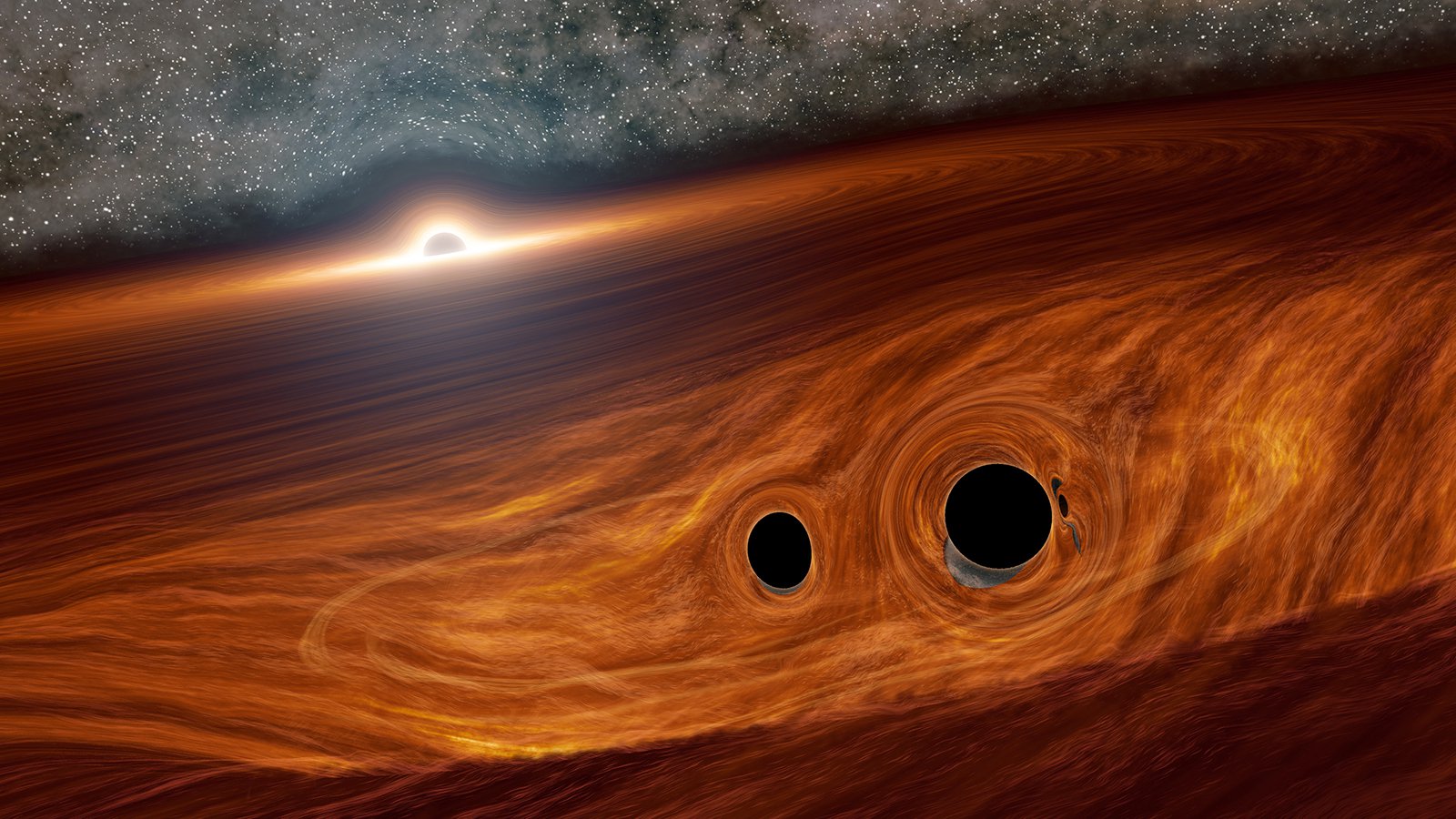

Gravitational-wave astronomy is still in its youth. Because of this, the gravitational waves we can observe come from powerful cataclysmic events. Black holes consuming each other in a violent chirp of spacetime, or neutron stars colliding in a tremendous explosion. Soon we might be able to observe the gravitational waves of supernovae, or supermassive black holes merging billions of light-years away. But underneath the cacophony is a very different gravitational wave. But if we can detect them, they will help us solve one of the deepest cosmological mysteries.

Continue reading “Next Generation Gravitational Wave Detectors Should be Able to see the Primordial Waves From the Big Bang”Merging Black Holes and Neutron Stars. All the Gravitational Wave Events Seen So Far in One Picture

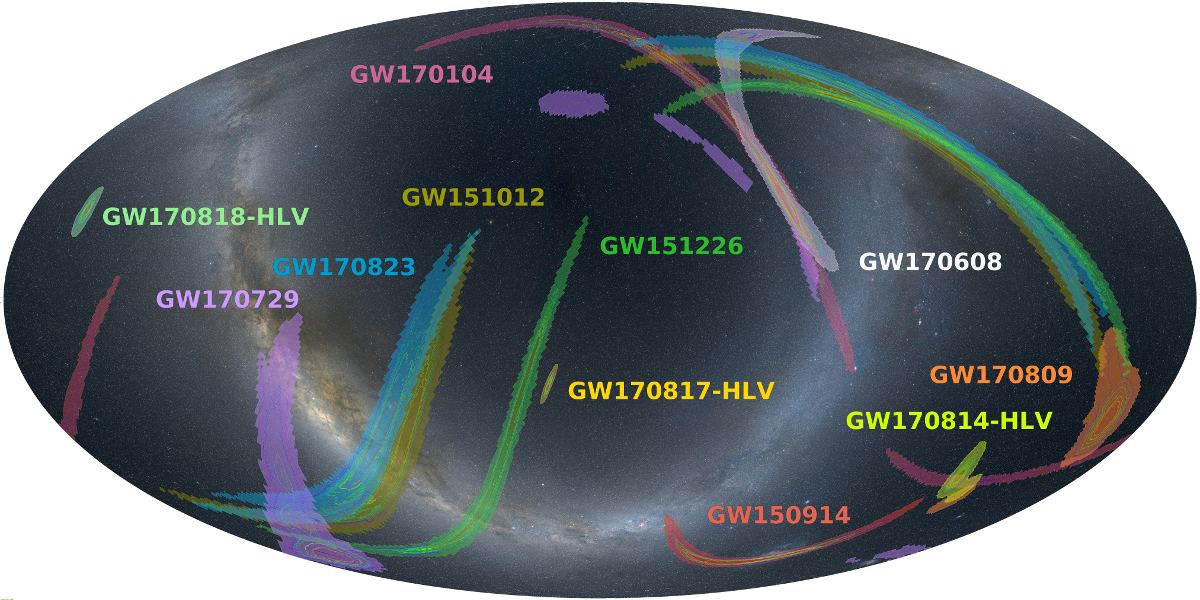

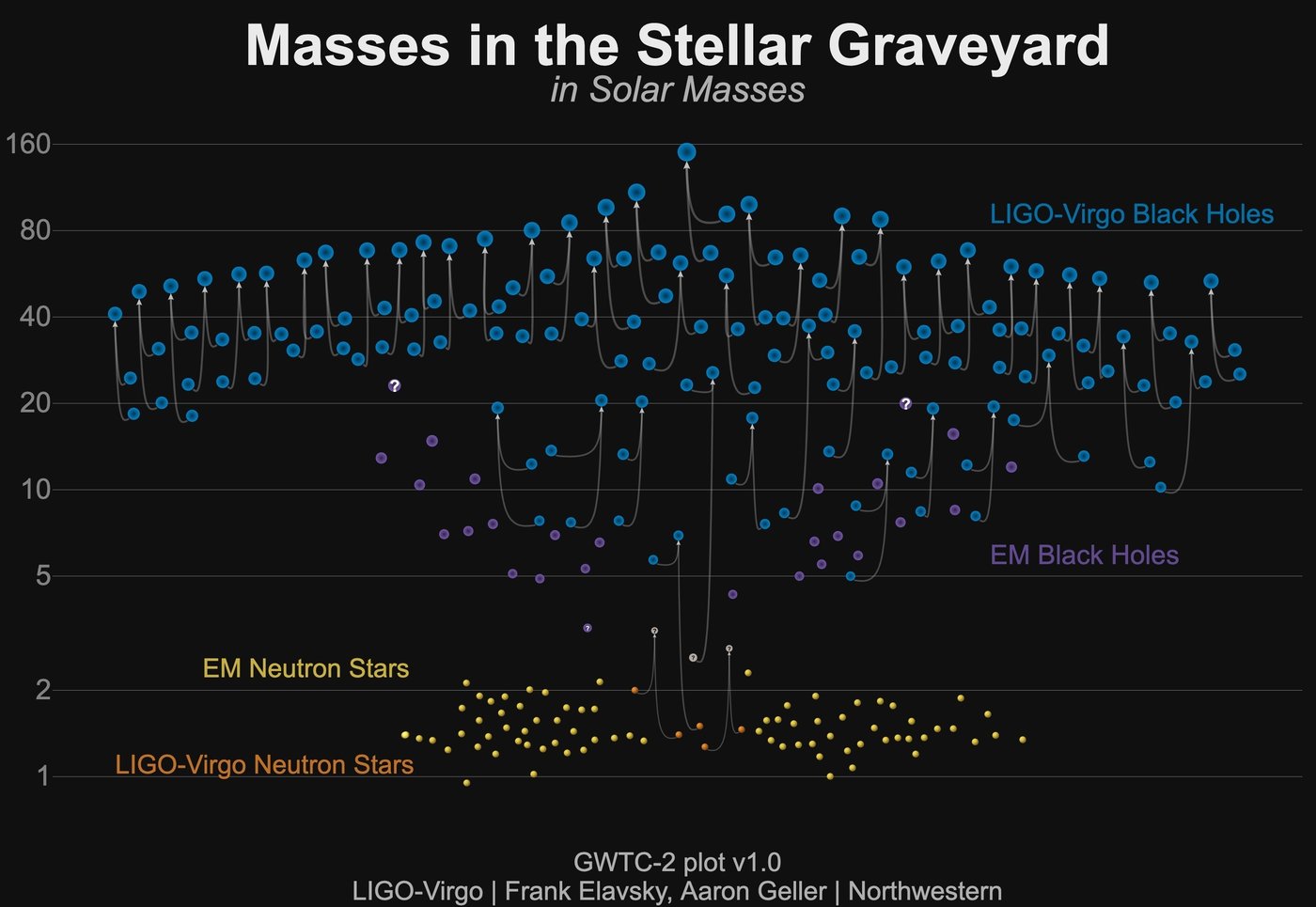

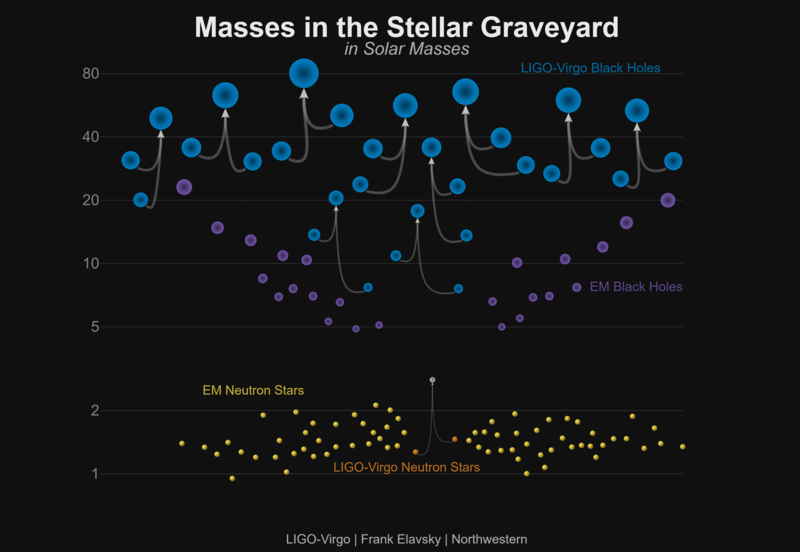

The Theory of Relativity predicted the existence of black holes and neutron stars. Einstein gets the credit for the theory because of his paper published in 1915, even though other scientists’ work helped it along. But regardless of the minds behind it, the theory predicted black holes, neutron stars, and the gravitational waves from their mergers.

It took about one hundred years, but scientists finally observed these mergers and their gravitational waves in 2015. Since then, the LIGO/Virgo collaboration has detected many of them. The collaboration has released a new catalogue of discoveries, along with a new infographic. The new infographic displays the black holes, neutron stars, mergers, and the other uncertain compact objects behind some of them.

Continue reading “Merging Black Holes and Neutron Stars. All the Gravitational Wave Events Seen So Far in One Picture”14% of all the Massive Stars in the Universe are Destined to Collide as Black Holes

Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity predicted that black holes would form and eventually collide. It also predicted the creation of gravitational waves from the collision. But how often does this happen, and can we calculate how many stars this will happen to?

A new study from a physicist at Vanderbilt University sought to answer these questions.

Continue reading “14% of all the Massive Stars in the Universe are Destined to Collide as Black Holes”LIGO Will Squeeze Light To Overcome The Quantum Noise Of Empty Space

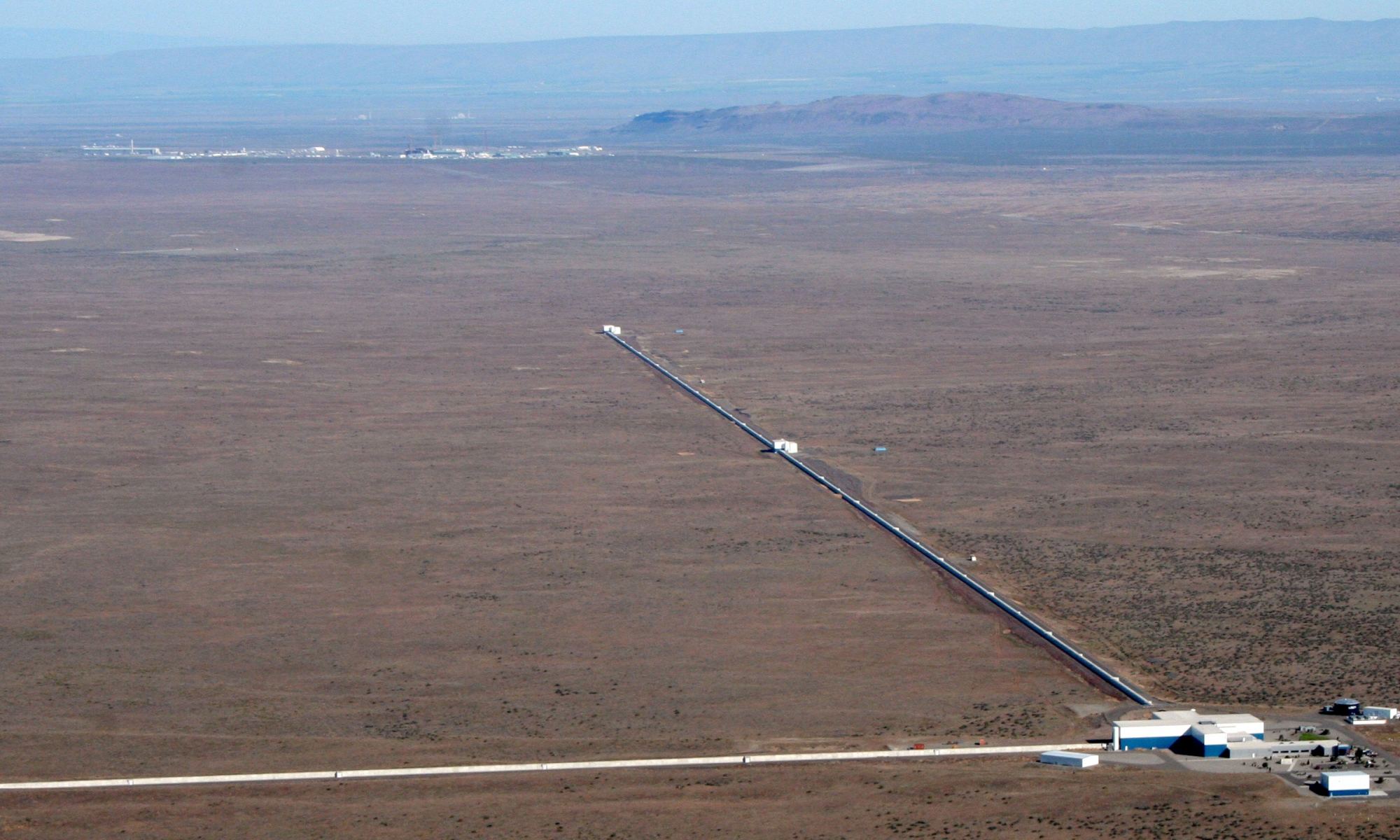

When two black holes merge, they release a tremendous amount of energy. When LIGO detected the first black hole merger in 2015, we found that three solar masses worth of energy was released as gravitational waves. But gravitational waves don’t interact strongly with matter. The effects of gravitational waves are so small that you’d need to be extremely close to a merger to feel them. So how can we possibly observe the gravitational waves of merging black holes across millions of light-years?

Continue reading “LIGO Will Squeeze Light To Overcome The Quantum Noise Of Empty Space”Hubble Has Looked at the 2017 Kilonova Explosion Almost a Dozen Times, Watching it Slowly Fade Away

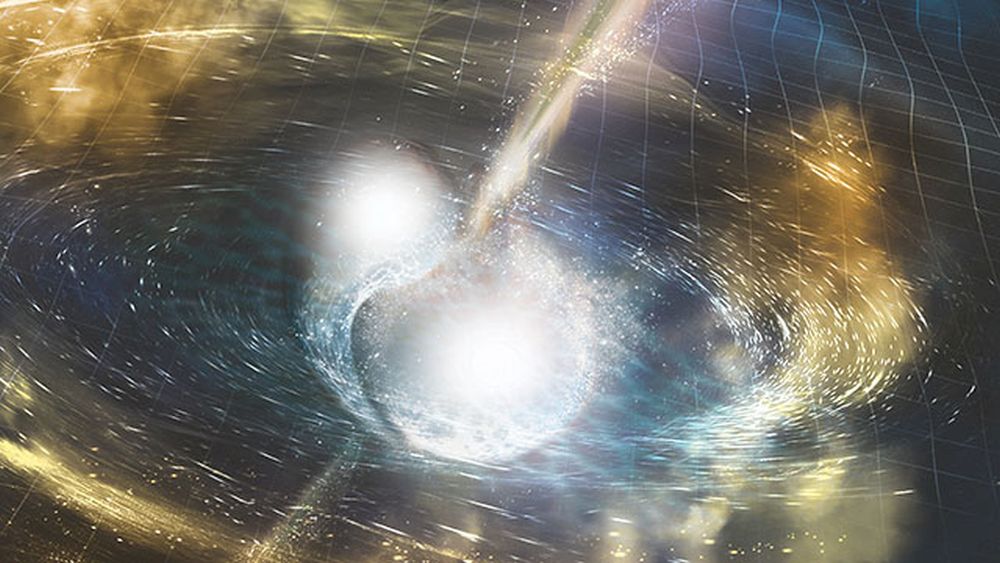

In 2017, LIGO (Laser-Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory) and Virgo detected gravitational waves coming from the merger of two neutron stars. They named that signal GW170817. Two seconds after detecting it, NASA’s Fermi satellite detected a gamma ray burst (GRB) that was named GRB170817A. Within minutes, telescopes and observatories around the world honed in on the event.

The Hubble Space Telescope played a role in this historic detection of two neutron stars merging. Starting in December 2017, Hubble detected the visible light from this merger, and in the next year and a half it turned its powerful mirror on the same location over 10 times. The result?

The deepest image of the afterglow of this event, and one chock-full of scientific detail.

Continue reading “Hubble Has Looked at the 2017 Kilonova Explosion Almost a Dozen Times, Watching it Slowly Fade Away”It Looks Like LIGO/Virgo Have Detected a Black Hole Eating a Neutron Star. For the First Time Ever

A new signal detected by LIGO/Virgo may be the so-called ‘holy grail’ of astrophysics: the merger of a neutron star and a black hole. They’ve discovered pairs of black holes merging, and pairs of neutron stars merging, but until now, not a neutron star-black hole pair.

Continue reading “It Looks Like LIGO/Virgo Have Detected a Black Hole Eating a Neutron Star. For the First Time Ever”New Gravitational Waves Detected From Four More Black Hole Mergers. Total Detections up to 11 Now

On February 11th, 2016, scientists at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) made history when they announced the first-ever detection of gravitational waves (GWs). Since that time, multiple detections have taken place and scientific collaborations between observatories – like Advanced LIGO and Advanced Virgo – are allowing for unprecedented levels of sensitivity and data sharing.

Previously, seven such events had been confirmed, six of which were caused by the mergers of binary black holes (BBH) and one by the merger of a binary neutron star. But on Saturday, Dec. 1st, a team of scientists the LIGO Scientific Collaboration (LSC) and Virgo Collaboration presented new results that indicated the discovery of four more gravitational wave events. This brings the total number of GW events detected in the last three years to eleven.