Europa is probably the best place in the Solar System to go searching for life. But before they’re launched, any spacecraft we send will need to be squeaky clean so don’t contaminate the place with our filthy Earth bacteria.

Continue reading “Will We Contaminate Europa?”

This Mountain on Mars Is Leaking

As the midsummer Sun beats down on the southern mountains of Mars, bringing daytime temperatures soaring up to a balmy 25ºC (77ºF), some of their slopes become darkened with long, rusty stains that may be the result of water seeping out from just below the surface.

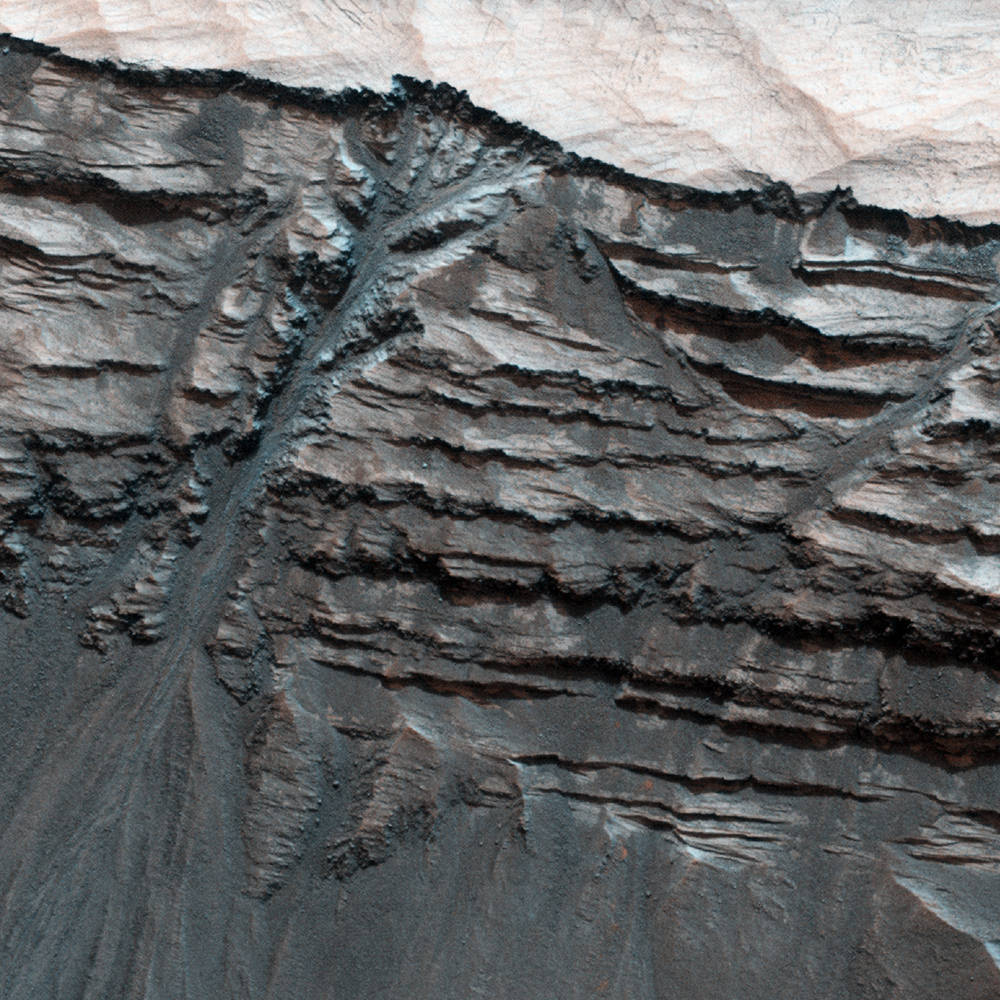

The image above, captured by the HiRISE camera aboard NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter on Feb. 20, shows mountain peaks within the 150-km (93-mile) -wide Hale Crater. Made from data acquired in visible and near infrared wavelengths the long stains are very evident, running down steep slopes below the rocky cliffs.

These dark lines, called recurring slope lineae (RSL) by planetary scientists, are some of the best visual evidence we have of liquid water existing on Mars today – although if RSL are the result of water it’s nothing you’d want to fill your astro-canteen with; based on the first appearances of these features in early Martian spring any water responsible for them would have to be extremely high in salt content.

According to HiRISE Principal Investigator Alfred McEwen “[t]he RSL in Hale have an unusually “reddish” color compared to most RSL, perhaps due to oxidized iron compounds, like rust.”

See a full image scan of the region here, and watch an animation of RSL evolution (in another location) over the course of a Martian season here.

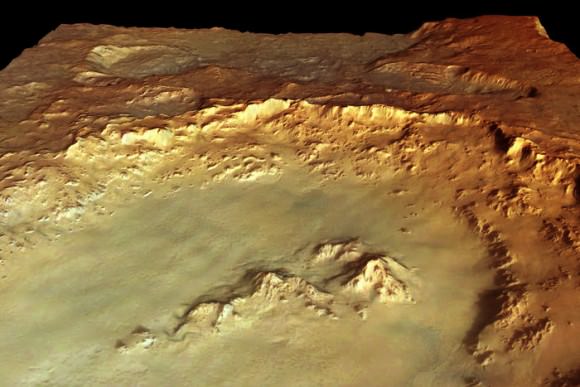

Hale Crater itself is likely no stranger to liquid water. Its geology strongly suggests the presence of water at the time of its formation at least 3.5 billion years ago in the form of subsurface ice (with more potentially supplied by its cosmic progenitor) that was melted en masse at the time of impact. Today carved channels and gullies branch within and around the Hale region, evidence of enormous amounts of water that must have flowed from the site after the crater was created. (Source.)

The crater is named after George Ellery Hale, an astronomer from Chicago who determined in 1908 that sunspots are the result of magnetic activity.

Read more on the University of Arizona’s HiRISE site here.

Sources: NASA, HiRISE and Alfred McEwen

UPDATE April 13: Conditions for subsurface salt water (i.e., brine) have also been found to exist in Gale Crater based on data acquired by the Curiosity rover. Gale was not thought to be in a location conducive to brine formation, but if it is then it would further strengthen the case for such salt water deposits in places where RSL have been observed. Read more here.

Where Should We Look for Life in the Solar System?

Emily Lakdawalla is the senior editor and planetary evangelist for the Planetary Society. She’s also one of the most knowledgeable people I know about everything that’s going on in the Solar System. From Curiosity’s exploration of Mars to the search for life in the icy outer reaches of the Solar System, Emily can give you the inside scoop.

In this short interview, Emily describes where she thinks we should be looking for life in the Solar System.

Follow Emily’s blog at the Planetary Society here.

Follow her on Twitter at @elakdawalla

And Circle her on Google+

Continue reading “Where Should We Look for Life in the Solar System?”

More Evidence of Liquid Erosion on Mars?

[/caption]

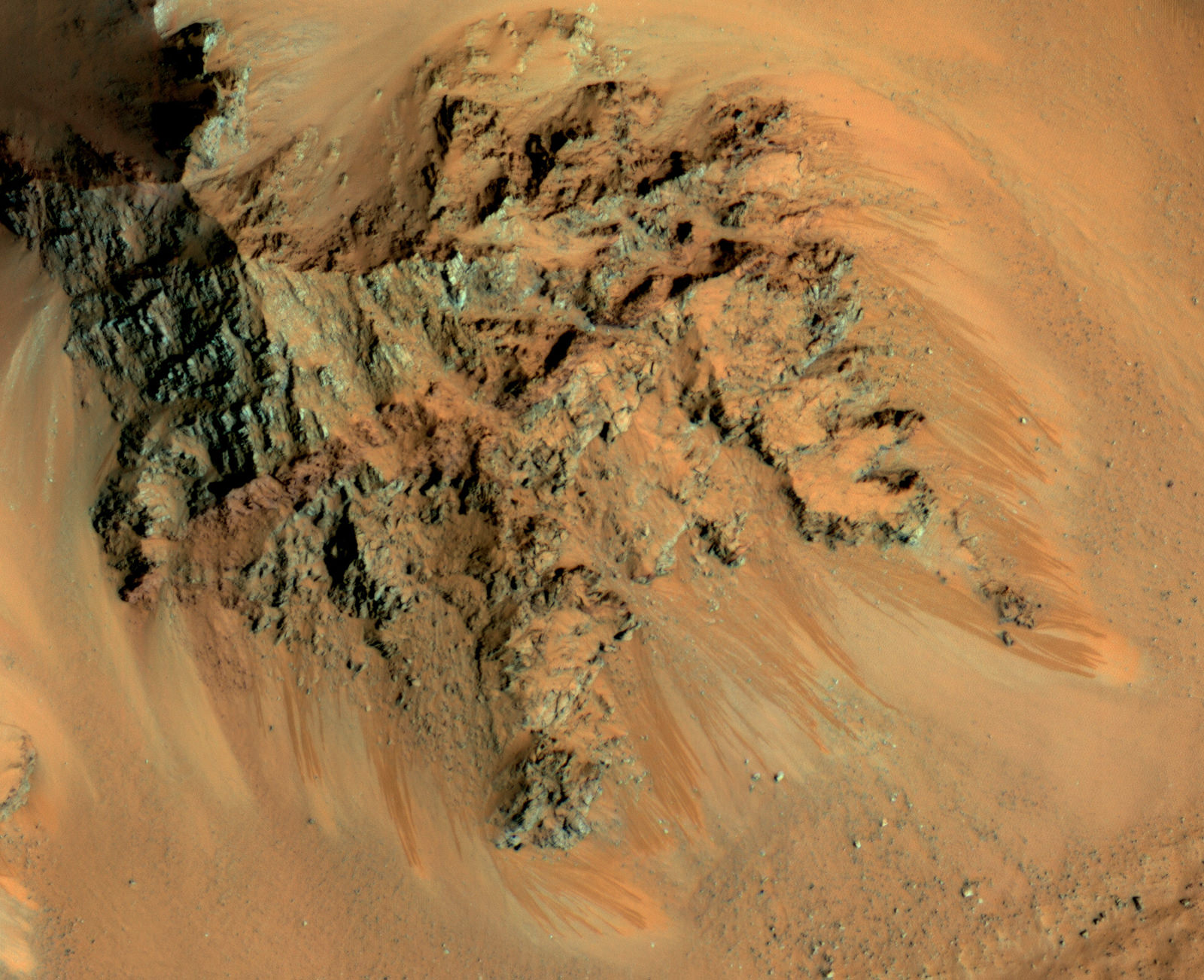

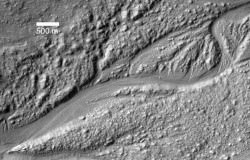

Terby Crater, a 170-km-wide (100-mile-wide) crater located on the northern edge of the vast Hellas Planitia basin in Mars’ southern hemisphere, is edged by variable-toned layers of sedimentary rock – possibly laid down over millennia of submersion beneath standing water. This image (false-color) from the HiRISE camera aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows a portion of Terby’s northern wall with what clearly looks like liquid-formed gullies slicing through the rock layers, branching from the upper levels into a main channel that flows downward, depositing a fan of material at the wall’s base.

But, looks can be deceiving…

Dry processes – especially on Mars, where large regions have been bone-dry for many millions of years – can often create the same effects on the landscape as those caused by running water. Windblown Martian sand and repetitive dry landslides can etch rock in much the same way as liquid water, given enough time. But the feature seen above in Terby seem to planetary scientists to be most likely the result of liquid erosion… especially considering that the sedimentary layers themselves seem to contain clay materials, which only form in the presence of liquid water. Is it possible that some water existed beneath Mars’ surface long after the planet’s surface dried out? Or that it’s still there? Only future exploration will tell for sure.

“While formation by liquid water is one of the proposed mechanisms for gully formation on Mars, there are others, such as gravity-driven mass-wasting (like a landslide) that don’t require the presence of liquid water. This is still an open question that scientists are actively pursuing.”

– Nicole Baugh, HiRISE Targeting Specialist

Terby Crater was once on the short list of potential landing sites for the new Mars Science Laboratory (aka Curiosity) rover but has since been removed from consideration. Still, it may one day be visited by a future robotic mission and have its gullies further explored from ground level.

Click here to see the original image on the HiRISE site.

Image credit: NASA / JPL / University of Arizona