Chalk another one up for Citizen Science. Earlier this month, researchers announced the discovery of 24 new pulsars. To date, thousands of pulsars have been discovered, but what’s truly fascinating about this month’s discovery is that came from culling through old data using a new method.

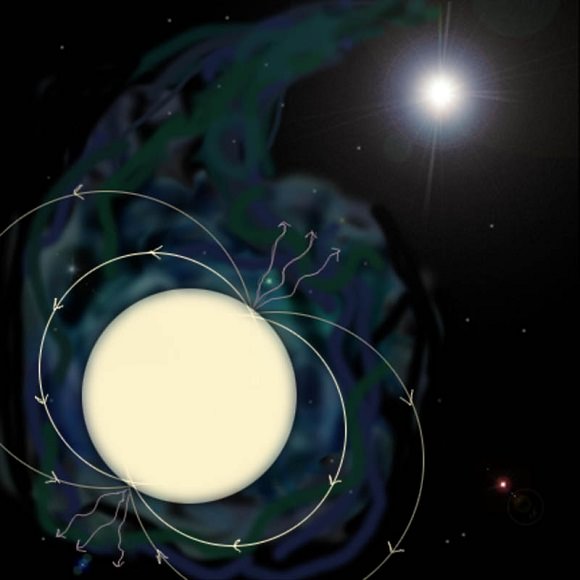

A pulsar is a dense, highly magnetized, swiftly rotating remnant of a supernova explosion. Pulsars where first discovered by Jocelyn Bell Burnell and Antony Hewish in 1967. The discovery of a precisely timed radio beacon initially suggested to some that they were the product of an artificial intelligence. In fact, for a very brief time, pulsars were known as LGM’s, for “Little Green Men.” Today, we know that pulsars are the product of the natural death of massive stars.

The data set used for the discovery comes from the Parkes 64-metre radio observatory based out of New South Wales, Australia. The installation was the first to receive telemetry from the Apollo 11 astronauts on the Moon and was made famous in the movie The Dish. The Parkes Multi-Beam Pulsar Survey (PMPS) was conducted in the late 1990’s, making thousands of 35-minute recordings across the plane of the Milky Way galaxy. This survey turned up over 800 pulsars and generated 4 terabytes of data. (Just think of how large 4 terabytes was in the 90’s!)

The nature of these discoveries presented theoretical astrophysicists with a dilemma. Namely, the number of short period and binary pulsars was lower than expected. Clearly, there were more pulsars in the data waiting to be found.

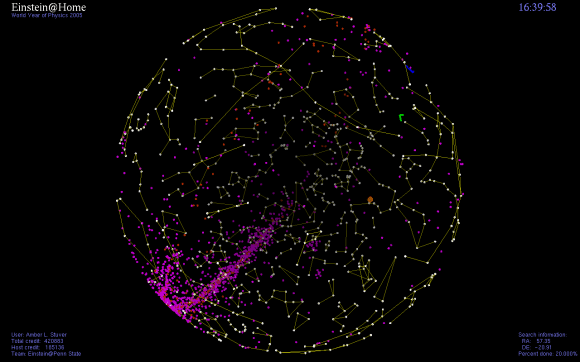

Enter Citizen Science. Using a program known as Einstein@Home, researchers were able to sift though the recordings using innovative modeling techniques to tease out 24 new pulsars from the data.

“The method… is only possible with the computing resources provided by Einstein@Home” Benjamin Knispel of the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics told the MIT Technology Review in a recent interview. The study utilized over 17,000 CPU core years to complete.

Einstein@Home is a program uniquely adapted to accomplish this feat. Begun in 2005, Einstein@Home is a distributed computing project which utilizes computing power while machines are idling to search through downloaded data packets. Similar to the original distributed computing program SETI@Home which searches for extraterrestrial signals, Einstein@Home culls through data from the LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory) looking for gravity waves. In 2009, the Einstein@Home survey was expanded to include radio astronomy data from the Arecibo radio telescope and later the Parkes observatory.

Among the discoveries were some rare finds. For example, PSR J1748-3009 Has the highest known dispersion measure of any millisecond pulsar (The dispersion measure is the density of free electrons observed moving towards the viewer). Another find, J1750-2531 is thought to belong to a class of intermediate-mass binary pulsars. 6 of the 24 pulsars discovered were part of binary systems.

These discoveries also have implications for the ongoing hunt for gravity waves by such projects as LIGO. Specifically, a through census of binary pulsars in the galaxy will give scientists a model for the predicted rate of binary pulsar mergers. Unlike radio surveys, LIGO seeks to detect these events via the copious amount of gravity waves such mergers should generate. Begun in 2002, LIGO consists of two gravity wave observatories, one in Hanford Washington and one in Livingston Louisiana just outside of Baton Rouge. Each LIGO detector consists of two 2 kilometre Fabry-Pérot arms in an “L” configuration which allow for ultra-precise measurements of a 200 watt laser beam shot through them. Two detectors are required to pin-point the direction of an incoming gravity wave on the celestial sphere. You can see the orientation of the “L’s” on the display on the Einstein@Home screensaver. Two geographically separate detectors are also required to rule out local interference. A gravity wave from a galactic source would ripple straight through the Earth.

Such a movement would be tiny, on the order of 1/1,000th the diameter of a proton, unnoticed by all except the LIGO detectors. To date, LIGO has yet to detect gravity waves, although there have been some false alarms. Scientists regularly interject test signals into the data to see if system catches them. The lack of detection of gravity waves by LIGO has put some constraints on certain events. For example, LIGO reported a non-detection of gravity waves during the February 2007 short gamma-ray burst event GRB 070201. The event arrived from the direction of the Andromeda Galaxy, and thus was thought to have been relatively nearby in the universe. Such bursts are thought to be caused by neutron star and/or black holes mergers. The lack of detection by LIGO suggests a more distant event. LIGO should be able to detect a gravitational wave event out to 70 million light years, and Advanced LIGO (AdLIGO) is set to go online in 2014 and will increase its sensitivity tenfold.

Knowledge of where these potential pulsar mergers are by such discoveries as the Parkes radio survey will also give LIGO researchers clues of targets to focus on. “The search for pulsars isn’t easy, especially for these “quiet” ones that aren’t doing the equivalent of “screaming” for our attention,” Says LIGO Livingston Data Analysis and EPO Scientist Amber Stuver. The LIGO consortium developed the data analysis technique used by Einstein@Home. The direct detection of gravitational waves by LIGO or AdLIGO would be an announcement perhaps on par with CERN’s discovery of the Higgs Boson last year. This would also open up a whole new field of gravitational wave astronomy and perhaps give new stimulus to the European Space Agencies’ proposed Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) space-based gravity wave detector. Congrats to the team at Parkes on their discovery… perhaps we’ll have the first gravity wave detection announcement out of LIGO as well in years to come!

-Read the original paper on the discovery of 24 new pulsars here.

-Amber Stuver blogs about Einstein@Home & the spin-off applications of gravity wave technology at Living LIGO.

-Parkes radio telescope image is copyrighted and used with the permission of CSIRO Operations Scientist John Sarkissian.

-For a fascinating read on the hunt for gravity waves, check out Gravity’s Ghost.