In 2015, then-NASA Chief Scientist Ellen Stofan stated that, “I believe we are going to have strong indications of life beyond Earth in the next decade and definite evidence in the next 10 to 20 years.” With multiple missions scheduled to search foe evidence of life (past and present) on Mars and in the outer Solar System, this hardly seems like an unrealistic appraisal.

But of course, finding evidence of life is no easy task. In addition to concerns over contamination, there is also the and the hazards the comes with operating in extreme environments – which looking for life in the Solar System will certainly involve. All of these concerns were raised at a new FISO conference titled “Towards In-Situ Sequencing for Life Detection“, hosted by Christopher Carr of MIT.

Carr is a research scientist with MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences (EAPS) and a Research Fellow with the Department of Molecular Biology at Massachusetts General Hospital. For almost 20 years, he has dedicated himself to the study of life and the search for it on other planets. Hence why he is also the science principal investigator (PI) of the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Genomes (SETG) instrument.

Led by Dr. Maria T. Zuber – the E. A. Griswold Professor of Geophysics at MIT and the head of EAPS – the inter-disciplinary group behind SETG includes researchers and scientists from MIT, Caltech, Brown University, arvard, and Claremont Biosolutions. With support from NASA, the SETG team has been working towards the development of a system that can test for life in-situ.

Introducing the search for extra-terrestrial life, Carr described the basic approach as follows:

“We could look for life as we don’t know it. But I think it’s important to start from life as we know it – to extract both properties of life and features of life, and consider whether we should be looking for life as we know it as well, in the context of searching for life beyond Earth.”

Towards this end, the SETG team seeks to leverage recent developments in in-situ biological testing to create an instrument that can be used by robotic missions. These developments include the creation of portable DNA/RNA testing devices like the MinION, as well as the Biomolecule Sequencer investigation. Performed by astronaut Kate Rubin in 2016, this was first-ever DNA sequencing to take place aboard the International Space Station.

Building on these, and the upcoming Genes in Space program – which will allow ISS crews to sequence and research DNA samples on site – the SETG team is looking to create an instrument that can isolate, detect, and classify any DNA or RNA-based organisms in extra-terrestrial environments. In the process, it will allow scientists to test the hypothesis that life on Mars and other locations in the Solar System (if it exists) is related to life on Earth.

To break this hypothesis down, it is a widely accepted theory that the synthesis of complex organics – which includes nucleobases and ribose precursors – occurred early in the history of the Solar System and took place within the Solar nebula from which the planets all formed. These organics may have then been delivered by comets and meteorites to multiple potentially-habitable zones during the Late Heavy Bombardment period.

Known as lithopansermia, this theory is a slight twist on the idea that life is distributed throughout the cosmos by comets, asteroids and planetoids (aka. panspermia). In the case of Earth and Mars, evidence that life might be related is based in part on meteorite samples that are known to have come to Earth from the Red Planet. These were themselves the product of asteroids striking Mars and kicking up ejecta that was eventually captured by Earth.

By investigating locations like Mars, Europa and Enceladus, scientists will also be able to engage in a more direct approach when it comes to searching for life. As Carr explained:

“There’s a couple main approaches. We can take an indirect approach, looking at some of the recently identified exoplanets. And the hope is that with the James Webb Space Telescope and other ground-based telescopes and space-based telescopes, that we will be in a position to begin imaging the atmospheres of exoplanets in much greater detail than characterization of those exoplanets has [allowed for] to date. And that will give us high-end, it will give the ability to look at many different potential worlds. But it’s not going to allow us to go there. And we will only have indirect evidence through, for example, atmospheric spectra.”

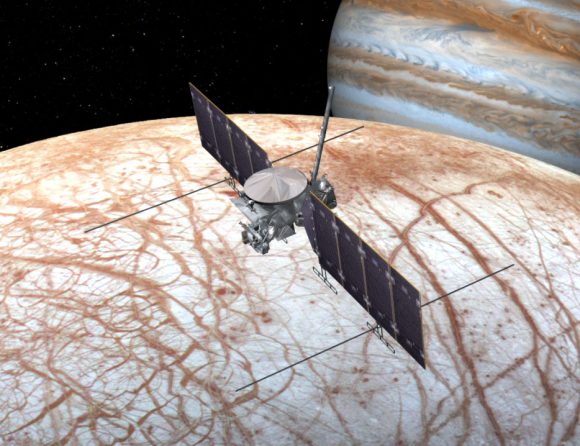

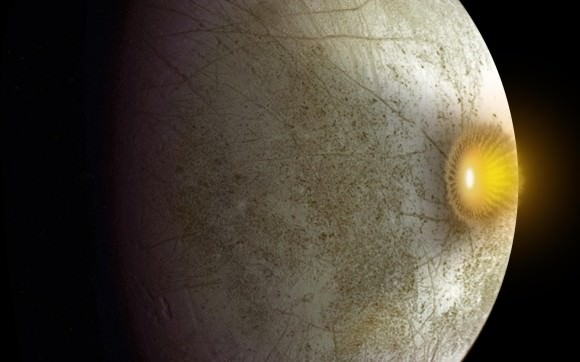

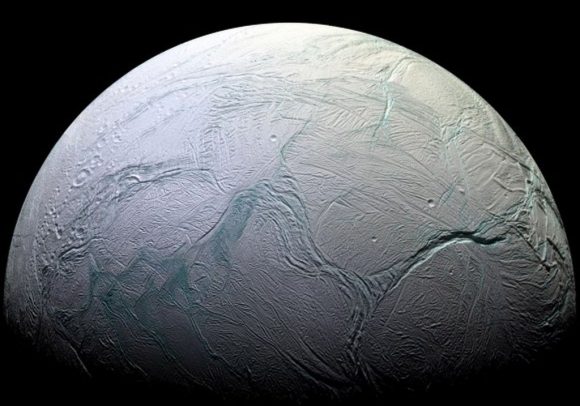

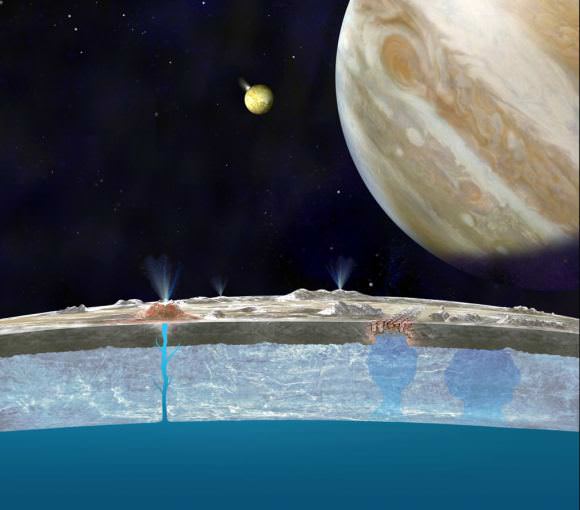

Mars, Europa and Enceladus present a direct opportunity to find life since all have demonstrated conditions that are (or were) conducive to life. Whereas there is ample evidence that Mars once had liquid water on its surface, Europa and Enceladus both have subsurface oceans and have shown evidence of being geologically active. Hence, any mission to these worlds would be tasked with looking in the right locations to spot evidence of life.

On Mars, Carr notes, this will come down to looking in places there there is a water-cycle, and will likely involve some a little spelunking:

“I think our best bet is to access the subsurface. And this is very hard. We need to drill, or otherwise access regions below the reach of space radiation which could destroy organic materiel. And one possibility is to go to fresh impact craters. These impact craters could expose material that wasn’t radiation-processed. And maybe a region where we might want to go would be somewhere where a fresh impact crater could connect to a deeper subsurface network – where we could get access to material perhaps coming out of the subsurface. I think that is probably our best bet for finding life on Mars today at the moment. And one place we could look would be within caves; for example, a lava tube or some other kind of cave system that could offer UV-radiation shielding and maybe also provide some access to deeper regions within the Martian surface.”

As for “ocean worlds” like Enceladus, looking for signs of life would likely involve exploring around its southern polar region where tall plumes of water have been observed and studied in the past. On Europa, it would likely involve seeking out “chaos regions”, the spots where there may be interactions between the surface ice and the interior ocean.

Exploring these environments naturally presents some serious engineering challenges. For starters, it would require the extensive planetary protections to ensure that contamination was prevented. These protections would also be necessary to ensure that false positives were avoided. Nothing worse than discovering a strain of DNA on another astronomical body, only to realize that it was actually a skin flake that fell into the scanner before launch!

And then there are the difficulties posed by operating a robotic mission in an extreme environment. On Mars, there is always the issue of solar radiation and dust storms. But on Europa, there is the added danger posed by Jupiter’s intense magnetic environment. Exploring water plumes coming from Enceladus is also very challenging for an orbiter that would most likely be speeding past the planet at the time.

But given the potential for scientific breakthroughs, such a mission it is well worth the aches and pains. Not only would it allow astronomers to test theories about the evolution and distribution of life in our Solar System, it could also facilitate the development of crucial space exploration technologies, and result in some serious commercial applications.

Looking to the future, advances in synthetic biology are expected to lead to new treatments for diseases and the ability to 3-D print biological tissues (aka. “bioprinting”). It will also help ensure human health in space by addressing bone density loss, muscle atrophy, and diminished organ and immune-function. And then there’s the ability to grow organisms specially-designed for life on other planets (can you say terraforming?)

On top of all that, the ability to conduct in-situ searches for life on other Solar planets also presents scientists with the opportunity to answer a burning question, one which they’ve struggled with for decades. In short, is carbon-based life universal? So far, any and all attempts to answer this question have been largely theoretical and have involved the “low hanging fruit variety” – where we have looked for signs of life as we know it, using mainly indirect methods.

By finding examples that come from environments other than Earth, we would be taking some crucial steps towards preparing ourselves for the kinds of “close encounters” that could be happening down the road.