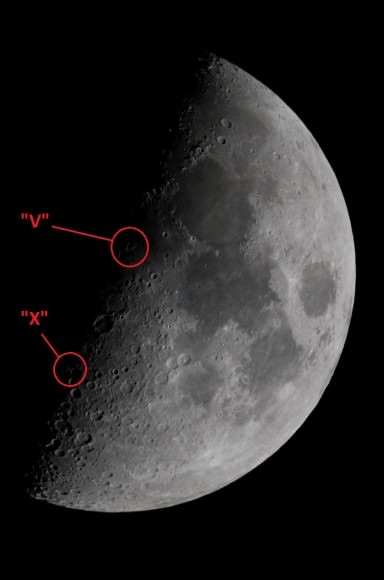

Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! What a great week to enjoy lunar features! We’ll celebrate many famous birthdays – including Charles Messier – and take on challenging double stars. If you’re in the mood to just kick back in a lawn chair and enjoy, then check out the June Draconid meteor shower. (sssssh… it may have been responsible for the Tunguska Blast!) Still more? Then keep an eye on the western horizon, because Mercury is about to become a “guest star” in the Beehive Cluster! When ever you’re ready, just meet me in the back yard…

Monday, June 25 – Today celebrates the birth of Hermann Oberth – who has often been considered the father of modern rocketry. Born in Transylvania in 1894, Oberth was a visionary who was convinced space travel would one day be possible. Inspired by the works of Jules Verne, Oberth studied rockets and wrote many books devoted to the possibility of achieving spaceflight. He was the first to conceive of rocket “stages” – allowing vehicles to expend their fuel and lose dead weight. But tonight you won’t need one of Oberth’s rockets to travel to the Moon, as take on another challenge as we look mid-way along the terminator at the west shore of Mare Tranquillitatis for crater Julius Caesar.

This is also a ruined crater, but it met its demise not through lava flow – but from a cataclysmic event. The crater is 88 kilometers long and 73 kilometers wide. Although its west wall still stands over 1200 meters high, look carefully at the east and south walls. At one time, something plowed its way across the lunar surface, breaking down Julius Caesar’s walls and leaving them to stand no higher than 600 meters at the tallest. While visiting the “Tranquil Sea”, look for the unusually shaped crater Hypatia. Can you spot its rima on the southern shore of Tranquillitatis? Perhaps the bright pockmark of Moltke on its north edge will help. Hypatia sits on the northern shore of a rugged area known as Sinus Asperitatis. Do you see Alfraganus on the terminator? Follow the terrain to Theophilus and look west for Ibyn-Rushd with crater Kant to the northwest and the beautiful peak of Mons Penck to its east.

Tuesday, June 26 – On this day in 1949, asteroid Icarus was discovered on a 48-inch Schmidt plate made nine months after that telescope went into operation, and just prior to the beginning of the multi-year National Geographic-Palomar Sky Survey. The asteroid was found to have a highly eccentric orbit and a perihelion distance of just 27 million kilometers, closer to the Sun than Mercury, giving it its unusual name. It was just 6.4 million kilometers from Earth at the time of discovery, and variations in its orbital parameters have been used to determine Mercury’s mass and test Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

But, today is even more special because it is the birthday of none other than Charles Messier, the famed French comet hunter. Born in 1730, Messier is best known for cataloging the 100 or so bright nebulae and star clusters that we now refer to as the Messier objects. The catalog was intended to keep both Messier and others from confusing these stationary objects with possible new comets.

] If you missed your chance last night to see the incredible Alpine Valley, it’s now fully disclosed in the sunlight. Viewable through binoculars as a thin, dark line, telescopic observers at highest powers will enjoy a wealth of details in this area, such as a crack running inside its boundaries. It’s a wonderful lunar observing challenge and a guide to our next lunar feature – Cassini and Cassini A. Where the valley joins the lunar Alps, follow the range south into Mare Imbrium. Along the way you will see the protruding bright peaks of Mons Blanc, Promontorium DeVille, and at the very end, Promontorium Agassiz ending in the smooth sands. Southeast of Agassiz you will spot Cassini. The major crater spans 57 kilometers and reaches a floor depth of 1240 meters. The challenge is to also spot the central crater A, which is only 17 kilometers wide, yet drops down another 2830 meters below the surface. This shallow crater holds another challenge within – Cassini A. But look carefully, can you spot the B crater on Cassini’s inner southwestern rim? Or the very small M crater just outside the northern edge?

For more advanced lunar observers, head a bit further south to the Haemus Mountains to look for the bright punctuation of a small crater on the southwest shore of Mare Serenitatis. Increase your magnification and look for a curious feature with an even more curious name… Rima Sulpicius Gallus. It is nothing more than a lunar wrinkle which accompanies the crater of the same name – a long-gone Roman counselor. Can you trace its 90 kilometer length?

Now see how many Messier objects that you can capture and wish Charles a happy birthday!

Wednesday, June 27 – Let’s begin our lunar studies tonight with a little “mountain climbing!” Using Copernicus as our guide, to the north and northwest of this ancient crater lie the Carpathian Mountains ringing the southern edge of Mare Imbrium. As you can see, they begin well east of the terminator, but look into the shadow! Extending some 40 kilometers beyond the line of daylight, you will continue to see bright peaks – some of which reach a height of 2072 meters. When the area is fully revealed tomorrow, you will see the Carpathian Mountains disappear into the lava flow that once formed them.

Let’s try looking just south of Sinus Medii and identifying these features: (1) Flammarion, (2) Herschel, (3) Ptolemaeus, (4) Alphonsus, (5) Davy, (6) Alpetragius, (7) Arzachel, (8) Thebit, (9) Purbach, (10) Lacaille, (11) Blanchinus, (12) Delaunay, (13) Faye, (14) Donati, (15) Airy, (16) Argelander, (17) Vogel, (18) Parrot, (19) Klein, (20) Albategnius, (21) Muller, (22) Halley, (23) Horrocks, (24) Hipparchus, (25) Sinus Medii

When skies are dark, it’s time to have a look at the 250 light-year distant silicon star Iota Librae. This is a real challenge for binoculars – but not because the components are so close. In Iota’s case, the near 5th magnitude primary simply overshadows its 9th magnitude companion! In 1782, Sir William Herschel measured them and determined them to be a true physical pair. Yet, in 1940 Librae A was determined to have an equal magnitude companion only .2 arc seconds away…. And the secondary was proved to have a companion of its own that echoes the primary. A four star system!

While you’re out, keep watch for a handful of meteors originating near the constellation of Corvus. The Corvid meteor shower is not well documented, but you might spot as many as ten per hour.

Thursday, June 28 – Tonight on the lunar surface, use crater Copernicus as a guide and look north-northwest to survey the Carpathian Mountains. The Carpathians ring the southern edge of Mare Imbrium beginning well east of the terminator. But let’s look on the dark side. Extending some 40 km beyond into the Moon’s own shadow, you can continue to see bright peaks – some reaching 2000 meters high! Tomorrow, when this area is fully revealed, you will see the Carpathians begin to disappear into the lava flow forming them. Continuing northward to Plato – on the northern shore of Mare Imbrium – re-identify the singular peak of Pico. Between Plato and Mons Pico you will find the many scattered peaks of the Teneriffe Mountains. It is possible that these are the remnants of much taller summits of a once precipitous range. Now the peaks rise less than 2000 meters above the surface.

Time to power up! West of the Teneriffes, and very near the terminator, you will see a narrow line of mountains, very similar in size to the Alpine Valley. This is known as the Straight Range or the Montes Recti. To binoculars or small scopes at low power, this isolated strip of mountains will appear as a white line drawn across the grey mare. It is believed this feature may be all that is left of a crater wall from the Imbrium impact. It runs for a distance of around 90 kilometers, and is approximately 15 kilometers wide. Some of its peaks reach as high as 2072 meters! Although this doesn’t sound particularly impressive, that’s over twice as tall as the Vosges Mountains in west-central Europe, and on the average very comparable to the Appalachian Mountains in the eastern United States.

When you’re finished with your lunar observations, tonight let’s try a challenging double star – Upsilon Librae. This beautiful red star is right at the limit for a small telescope, but quite worthy as the pair is a widely disparate double. Look for the 11.5 magnitude companion to the south in a very nice field of stars!

Friday, June 29 – Today we celebrate the birthday of George Ellery Hale, who was born in 1868. Hale was the founding father of the Mt. Wilson Observatory. Although he had no education beyond his baccalaureate in physics, he became the leading astronomer of his day. He invented the spectroheliograph, coined the word astrophysics, and founded the Astrophysical Journal and Yerkes Observatory. At the time, Mt. Wilson dominated the world of astronomy, confirming what galaxies were and verifying the expanding universe cosmology, making Mt. Wilson one of the most productive facilities ever built. When Hale went on to found Palomar Observatory, the 5-meter (200?) telescope was named for him and dedicated on June 3, 1948. It continues to be the largest telescope in the continental United States.

It’s time to head deeper toward the lunar south as we take a close look at the dark, heart-shaped region Palus Epidemiarum. Caught on its southern edge is the largely eroded Campanus with well defined Cichus to the east and Ramsden to the west. Power up in your telescope and look carefully at its smooth floors. If conditions are favorable, you will catch Rima Hesiodus cutting across its northern boundary and the crisscross pattern of Rima Ramsden in the western lobe. Can you make out a small, deep puncture mark to the northeast? It might be small, but it has a name – Marth.

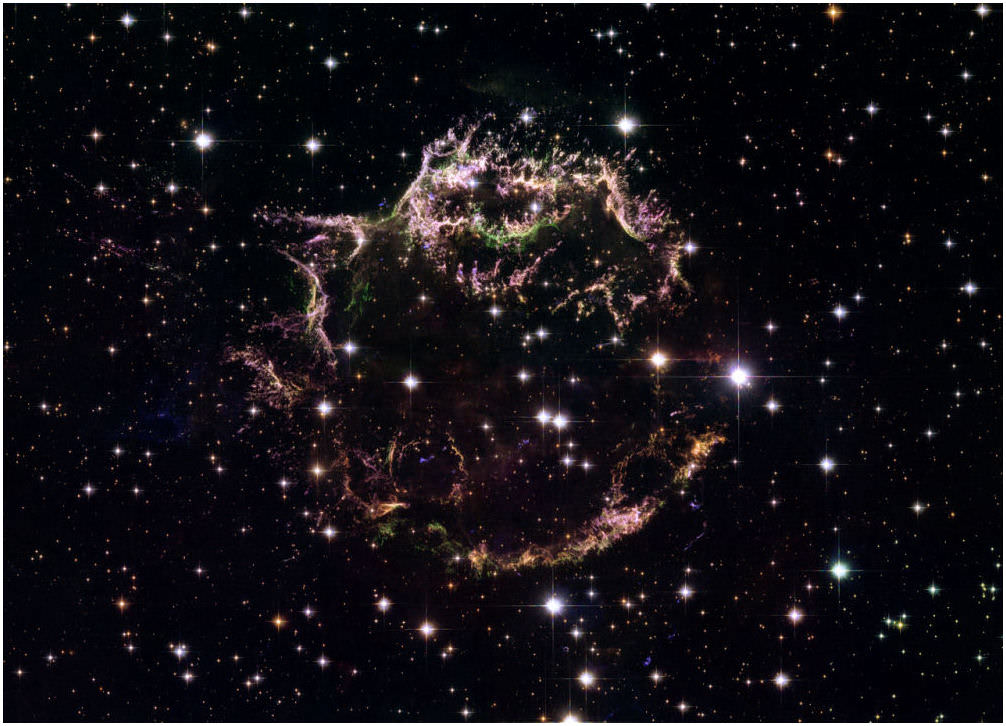

Now let’s go deep south and have look at an area which once held something almost half a bright as tonight’s Moon and over four times brighter than Venus. Only one thing could light up the skies like that – a supernova. According to historical records from Europe, China, Egypt, Arabia and Japan, 1001 years ago the very first supernova event was noted. Appearing in the constellation of Lupus, it was at first believed to be a comet by the Egyptians, yet the Arabs saw it as an illuminating “star.”

Located less than a fingerwidth northeast of Beta Lupus (RA 15 02 48.40 Dec -41 54 42.0) and a half degree east of Kappa Centaurus, no visible trace is left of a once grand event that spanned five months of observation beginning in May, and lasting until it dropped below the horizon in September, 1006. It is believed all the force created from the event was converted to energy and very little mass remains. In the area, a 17th magnitude star shows a tiny gas ring and radio source 1459-41 remains our best candidate for pinpointing this incredible event.

Saturday, June 30 – We start our observing evening with the beautiful Moon as we return first to the ancient and graceful landmark crater Gassendi standing at the north edge of Mare Humorum. The mare itself is around the size of the state of Arkansas and is one of the oldest of the circular maria on the visible surface. As you view the bright ring of Gassendi, look for evidence of the massive impact which may have formed Humorum. It is believed the original crater may have been in excess of 462 kilometers in diameter, indenting the lunar surface almost twice over. Over time, similar smaller strikes formed the many craters around its edges and lava flow gradually gave the area the ridge- and rille-covered floor we see tonight. Its name is the “Sea of Moisture,” but look for its frozen waves in the long dry landscape.

Caught on the north-western rim of Mare Humorum, look for crater Mersenius. It is a typical Nectarian geological formation, spanning approximately 51 miles in diameter in all directions. Power up in a telescope to look for fine features such as steep slopes supporting newer impact crater Mersenius P and tiny interior craterlet chains. Can you spot white formations and crevices along its terraced walls? How about Rimae Mersenius? Further south you’ll spy tiny Liebig helping to support Mersenius D’s older structure, along with its own small set of mountains known as the Rupes Liebig. Continue to follow the edge of Mare Humorum around the wall known as Rimae Doppelmayer until you reach the shallow old crater Doppelmayer. As you can see, the whole floor fractured crater has been filled with lava flow from Mare Humorum’s formation, pointing to an age older than Humorum itself. Look for a shallow mountain peak in its center – there’s a very good chance this peak is actually higher than the crater walls. Did this crater begin to upwell as it filled? Or did it experience some volcanic activity of its own? Take a closer look at the floor if the lighting is right to spy a small lava dome and evidence of dark pyroclastic deposits – it’s a testament to what once was!

Still got the moonlight blues? Then try your hand at a super challenging double – Mu Librae. This pair is only a magnitude apart in brightness and right at the limit for a small telescope. Up the power slowly and look for the companion just to the southwest of the primary. Good luck and mark your observation because Mu’s blues are on many observing lists!

And out of the blue comes a meteor shower! Keep watch tonight for the June Draconids. The radiant for this shower will be near handle of Big Dipper – Ursa Major. The fall rate varies from 10 to 100 per hour, but tonight’s bright skies will toast most of the offspring of comet Pons-Winnecke. On a curious note, today in 1908 was when the great Tunguska impact happened in Siberia. A fragment of a comet, perhaps?

Sunday, July 1 – Today In 1917, the astronomers at Mt. Wilson were celebrating as the 100? primary mirror arrived. Up until that time, the 60? Hale telescope (donated by George Hale’s father) was the premier creation of St. Gobrain Glassworks – which was later commissioned to create the blank for the Hooker telescope. Thanks to the funds provided by John D. Hooker (and Carnegie), the dream was realized after years of hard work and ingenuity to create not only a building to properly house it – but the telescope workings as well. It saw “first light” five months later on November 1.

As anxious astronomers waited for this groundbreaking moment, the scope was aimed at Jupiter but the image was horrible – to their dismay, workmen had left the dome open and the Sun had heated the massive mirror! Try as they might to rest until it had cooled – no astronomer slept. Fearful of the worst, sometime around three in the morning they returned again long after Jupiter had set. Pointing the massive scope towards a star, they achieved a perfect image!

If you’re looking for a perfect image, then look no further than the western horizon tonight at twilight. Why? Because Mercury is going to be a “guest star” in the Beehive Cluster! Be sure to at least get out your binoculars and look at the speedy little inner planet as it cruises about a degree or so to the western edge of M44.

Tonight we’ll return again to our landmark lunar feature – crater Grimaldi – and begin our journey north…

As you move north of Grimaldi on a crater hop, the next feature you will en-counter is the walled plain of Hevelius. With a diameter of about 64 miles, this round area doesn’t have a height we can really measure because of its lunar position, but we can see that it does have some relatively steep walls around its edges. Hevelius was formed in the Nectarian geological period and if you look closely you’ll see that it has a small central peak, a fine rimae and many craterlet chains, too. Can you spot large interior Crater Hevelius A with just binoculars? How about companion crater Cavalerius which is part of its northern border?

While you’re out, take the time to look at lowly Theta Lupi about a fistwidth south-southwest of the mighty Antares. While this rather ordinary looking 4th magnitude star appears to be nothing special – there’s a lesson to be learned here. So often in our quest to look at the bright and incredible – the distant and the impressive – we often forget about the beauty of a single star. When you take the time to seek the path less traveled, you just might find more than you expected. Hiding behind a veil of the “ordinary” lies a trio of three spectral types and three magnitudes in a diamond-dust field. An undiscovered gem…

Until next week? Ask for the Moon, but keep on reaching for the stars!