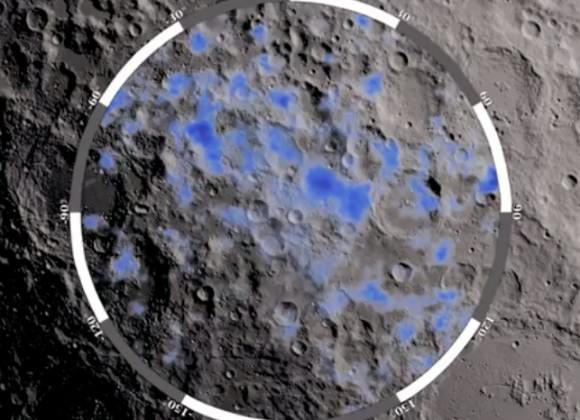

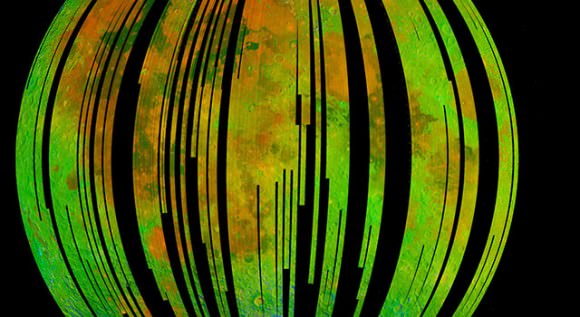

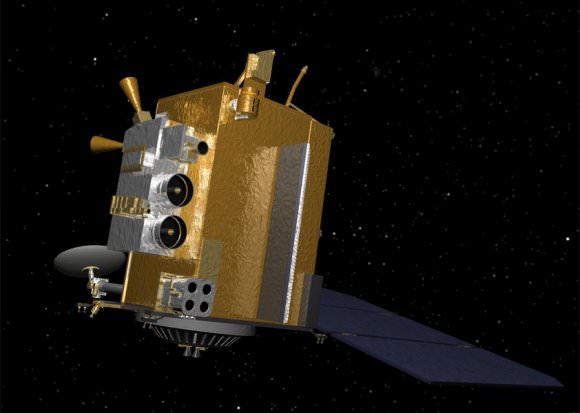

On October 13th, 2014, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) experienced something rare and unexpected. While monitoring the surface of the Moon, the LRO’s main instrument – the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC) – produced an image that was rather unusual. Whereas most of the images it has produced were detailed and exact, this one was subject to all kinds of distortion.

From the way this image was disturbed, the LRO science team theorized that the camera must have experienced a sudden and violent movement. In short, they concluded that it had been struck by a tiny meteoroid, which proved to a significant find in itself. Luckily, the LRO and its camera appear to have survived the impact unharmed and will continue to survey the surface of the Moon for years to come.

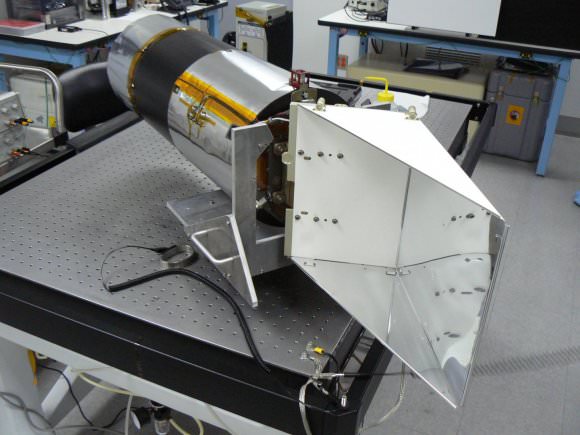

The LROC is a system of three cameras that are mounted aboard the LRO spacecraft. This include two Narrow Angle Cameras (NACs) – which capture high-resolution black and white images – and a third Wide Angle Camera (WAC), which captures moderate resolution images that provide information about the properties and color of the lunar surface.

The NACs works by building an image one line at a time, with thousands of lines being used to compile a full image. In between the capture process, the spacecraft moves the camera relative to the surface. On October 13th, 2014, at precisely 21:18:48 UTC, the camera added a line that was visibly distorted. This sent the LRO team on a mission to investigate what could have caused it.

Led by Mark Robinson – a professor and the principal investigator of the LROC at Arizona State University’s School of Earth and Space Exploration – the LROC researchers concluded that the left Narrow Angle Camera must have experienced a brief and violent movement. As there were no spacecraft events – like a solar panel movement or antenna tracking – that might have caused this, the only possibility appeared to be a collision.

As Robinson explained in a recent post on the LROC’s website:

“There were no spacecraft events (such as slews, solar panel movements, antenna tracking, etc.) that might have caused spacecraft jitter during this period, and even if there had been, the resulting jitter should have affected both cameras identically… Clearly there was a brief violent movement of the left NAC. The only logical explanation is that the NAC was hit by a meteoroid! How big was the meteoroid, and where did it hit?”

To test this, the team used a detailed computer model that was developed specifically for the LROC to ensure that the NAC would not fail during the launch of the spacecraft, when severe vibrations would occur. With this model, the LROC team ran simulations to see if they could reproduce the distortions that would have caused the image. Not only did they conclude it was the result of a collision, but they were also able to determine the size of the meteoroid that hit it.

The results indicated that the impacting meteoroid would have measured about 0.8 mm in diameter and had a density of a regular chondrite meteorite (2.7 g/cm³). What’s more, they were able to estimate that it was traveling at a velocity of about 7 km/s (4.3 miles per second) when it collided with the NAC. This was rather surprising, given the odds of collisions and how much time the LRO spends gathering data.

Typically, the LROC only captures images during daylight hours, and for about 10% of the day. So for it to have been hit while it was also capturing images is statistically unlikely – only about 5% by Robinson’s own estimate. Luckily, the impact has not caused any technical problems for the LROC, which is also something of a minor miracle. As Robinson explained:

“For comparison, the muzzle velocity of a bullet fired from a rifle is typically 0.5 to 1.0 kilometers per second. The meteoroid was traveling much faster than a speeding bullet. In this case, LROC did not dodge a speeding bullet, but rather survived a speeding bullet! LROC was struck and survived to keep exploring the Moon, thanks to Malin Space Science Systems’ robust camera design.”

It was only after the team deduced that no damage had been caused that prompted the announcement. According to John Keller, the LRO project scientist from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, the real story here was how the imagery that was being acquired at the time was used to deduce how and when the LRO had been struck by a meteoroid.

“Since the impact presented no technical problems for the health and safety of the instrument,” he said, “the team is only now announcing this event as a fascinating example of how engineering data can be used, in ways not previously anticipated, to understand what is happening to the spacecraft over 236,000 miles (380,000 kilometers) from the Earth.”

In addition, the impact of a meteoroid on the LRO demonstrates just how precious the information that missions like the LRO provides truly is. Beyond mapping the lunar surface, the orbiter was also able to let its science team know exactly and when its images were comprised, all because of the high-quality data it collects.

Since it launched in June of 2008, the LRO has collected an immense amount of data on the lunar surface. The mission has been extended several times, from its original duration of two years to the just under nine. Its ongoing performance is also a testament to the durability of the craft and its components.

Be sure to enjoy this video of the images obtained by the LRO, courtesy of the LROC team:

Further Reading: ASU/LROC