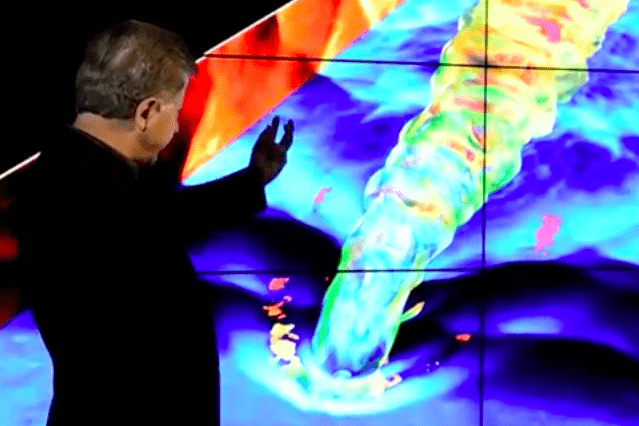

Researchers at Stanford University are working on solutions to the inherent difficulties of hypersonic flight — speeds of over Mach 5, or 3,000 mph (4828 km/h) — and they’ve created one amazing computer model illustrating the dynamics of air temperature variations created at those intense speeds.

[/caption]

According to a news article from Stanford University, “Real-world laboratories can only go so far in reproducing such conditions, and test vehicles are rendered extraordinarily vulnerable. Of the U.S. government’s three most recent tests, two ended in vehicle failure.”

The video above shows some of the research team’s animation model — one of if not the largest engineering calculation ever created, it ran on 163,000 processors simultaneously and took 4 days to complete! And it’s utterly mesmerizing… not to mention invaluable to researchers.

“It’s something you could never have created unless you put computer scientists, mathematicians, mechanical engineers and aerospace engineers together in the same room,” said Juan Alonso, associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at Stanford. “Do it, though, and you can produce some really magical results.”

In a (very tiny) nutshell, the behavior of air through an hypersonic engine — called a scramjet (for supersonic combustion ramjet) — changes at extremely high speeds. In order for aircraft to travel and maneuver reliably the scramjets have to be engineered to account for the way the air will respond.

“If you put too much fuel in the engine when you try to start it, you get a phenomenon called ‘thermal choking,’ where shock waves propagate back through the engine,” explained Parviz Moin, the Franklin P. and Caroline M. Johnson Professor in the School of Engineering. “Essentially, the engine doesn’t get enough oxygen and it dies. It’s like trying to light a match in a hurricane.”

“Understanding and being able to predict this phenomena has been one of the big challenges. It’s not one number or two numbers that come out of it at the end of the day… it is all of these structures that you see back there, the richness of it. It is understanding that allows you to control.”

– Parvis Moin, Stanford University professor

Thanks to this study, made possible by a 5-year $20 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy, we may one day have aircraft that can travel up to 15 times the speed of sound. But the team’s groundbreaking computations aren’t just reserved for aeronautic aspirations.

“These same technologies can be used to quantify flow of air around wind farms, for example, or for complex global climate models,” said Alonso.

Read more on the Stanford University News here.

Video by Steve Fyffe and Linda Cicero. Source: Stanford University.