[/caption]

Although well over 40 years old, the Dunn Solar Telescope at Sunspot, New Mexico isn’t going to be looking at an early retirement. On the contrary, it has been outfitted with the new Facility Infrared Spectropolarimeter (FIRS) and is already making news on its solar findings. FIRS provides simultaneous spectral coverage at visible and infrared wavelengths through the use of a unique dual-armed spectrograph. By utilizing adaptive optics to overcome atmospheric “seeing” conditions, the team took on seven active regions on the Sun – one in 2001 and six during December 2010 to December 2011 – as Sunspot Cycle 23 faded away. The full sunspot sample has 56 observations of 23 different active regions… and showed that hydrogen might act as a type of energy dissipation device which helps the Sun get a magnetic grip on its spots.

“We think that molecular hydrogen plays an important role in the formation and evolution of sunspots,” said Dr. Sarah Jaeggli, a recent University of Hawaii at Manoa graduate whose doctoral research formed a key element of the new findings. She conducted the research with Drs. Haosheng Lin, also from the University of Hawaii at Manoa, and Han Uitenbroek of the National Solar Observatory in Sunspot, NM. Jaeggli now is a postdoctoral researcher in the solar group at Montana State University. Their work is published in the February 1, 2012, issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

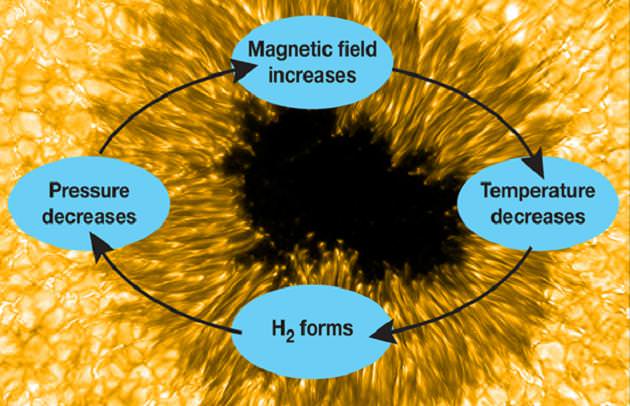

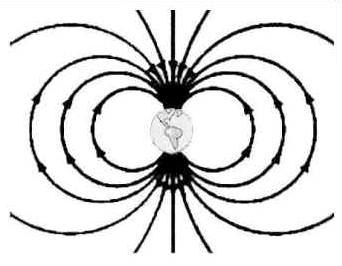

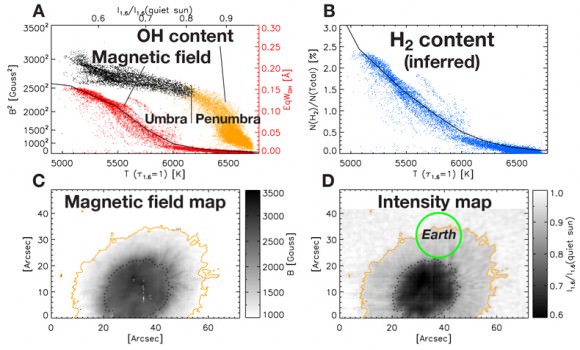

You don’t have to be a solar physicist to know about the Sun’s 11 year cycle, or to understand how sunspots are cooler areas of intense magnetism. Believe it or not, even the professionals aren’t quite sure of how all the mechanisms work… especially those which cause sunspot forming areas that retard normal convective motions. Of the things we’ve learned, the spot’s inner temperature has a correlation with its magnetic field strength – with a sharp rise as the temperature cools. “This result is puzzling,” Jaeggli and her colleagues wrote. It implies some undiscovered mechanism inside the spot.

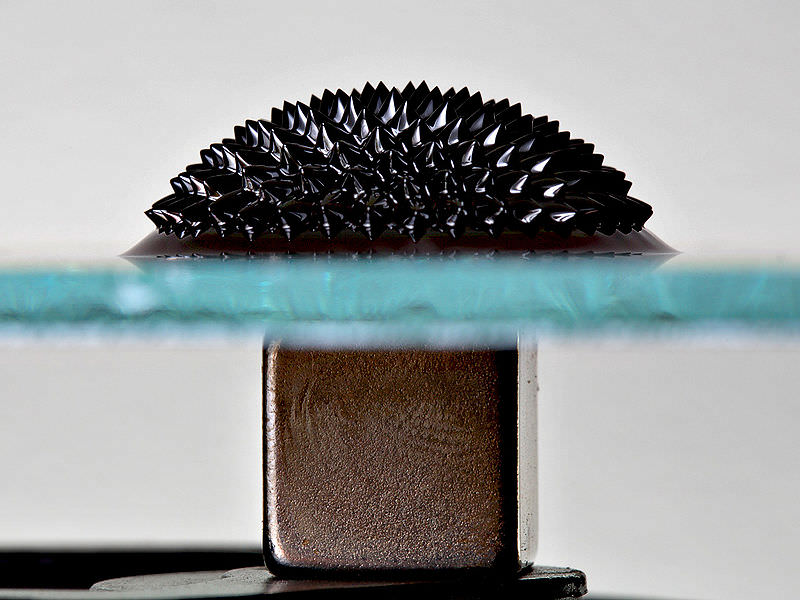

One theory is that hydrogen atoms combining into hydrogen molecules may be responsible. As for our Sun, the majority of hydrogen is ionized atoms because the average surface temperature is assessed at 5780K (9944 deg. F). However, since Sol is considered a “cool star”, researchers have found indications of heavy-element molecules in the solar spectrum – including surprising water vapor. These type of findings might prove the umbral regions could allow hydrogen molecules to combine in the surface layers – a prediction of 5% made by the late Professor Per E. Maltby and colleagues at the University of Oslo. This type of shift could cause drastic dynamic changes where gas pressure is concerned.

“The formation of a large fraction of molecules may have important effects on the thermodynamic properties of the solar atmosphere and the physics of sunspots,” Jaeggli wrote.

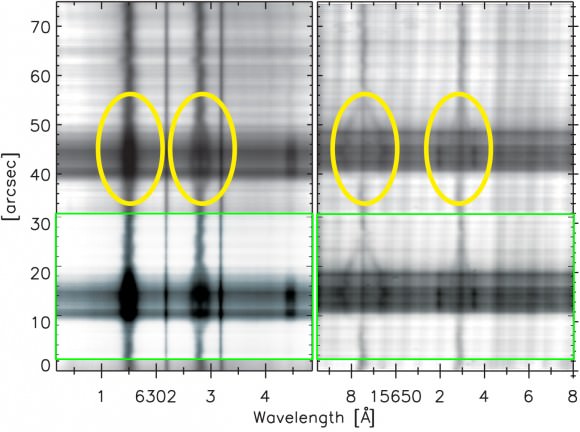

With direct measurements being beyond our current capabilities, the team then measured a proxy – the hydroxyl radical made of one atom each of hydrogen and oxygen (OH). According to the National Solar Observatory, “OH dissociates (breaks into atoms) at a slightly lower temperature than H2, meaning H2 can also form in regions where OH is present. By coincidence, one of its infrared spectral lines is 1565.2nm, almost the same as the 1565nm line of iron, used for measuring magnetism in a spot and one of the lines FIRS is designed to observe.”

By combining both old and new data, the team measured magnetic fields across sunspots, and the OH intensity inside spots, judging the H2 concentrations. “We found evidence that significant quantities of hydrogen molecules form in sunspots that are able to maintain magnetic fields stronger than 2,500 Gauss,” Jaeggli commented. She also said its presence leads to a temporary “runaway” intensification of the magnetic field.

As for the anatomy of a sunspot, magnetic flux boils up from the Sun’s interior and slows surface convection – which in turns stops cooler gas which has radiated its heat into space. From there, molecular hydrogen is created, reducing the volume. Because it is more transparent than its atomic counterpart, its energy is also radiated into space allowing the gas to cool even more. At this point the hot gas primed by the flux compresses the cooler region and intensifies the magnetic field. “Eventually it levels out, partly from energy radiating in from the surrounding gas. Otherwise, the spot would grow without bounds. As the magnetic field weakens, the H2 and OH molecules heat up and dissociate back to atoms, compressing the remaining cool regions and keeping the spot from collapsing.”

For now, the team admits that additional computer modeling is required to validate their observations and that most of the active regions so far have been mild ones. They’re hoping that Sunspot Cycle 24 will give them more fuel to be “cool”…

Original Story Source: National Solar Observatory News Release.