Mars’ atmosphere consists of 95% carbon dioxide, 3% nitrogen, 1.6% argon, and contains small amounts of oxygen and water, as well as trace amounts of methane. The methane – although small in percentage – might be the most intriguing because the source of this very short-lived gas remains a mystery. And the mystery has just gotten a little more puzzling, as the lifetime of methane in Mars atmosphere appears to be even shorter than scientists had originally thought. Using observations from the Mars Global Surveyor — which functioned in orbit around for almost ten years – a group of scientists from Italy have determined the methane in the atmosphere of Mars lasts less than a year.

Scientists Sergio Fonti (Università del Salento) and Giuseppe Marzo (NASA Ames) reported their findings of evolution of the methane over three Martian years at the European Planetary Science Congress in Rome.

“Only small amounts of methane are present in the Martian atmosphere, coming from very localized sources,” said Fonti. “ We’ve looked at changes in concentrations of the gas and found that there are seasonal and also annual variations. The source of the methane could be geological activity or it could be biological – we can’t tell at this point. However, it appears that the upper limit for methane lifetime is less than a year in the Martian atmosphere.”

Levels of methane are highest in autumn in the northern hemisphere, with localized peaks of 70 parts per billion, although methane can be detected across most of the planet at this time of year. There is a sharp decrease in winter, with only a faint band between 40-50 degrees north. Concentrations start to build again in spring and rise more rapidly in summer, spreading across the planet.

“One of the interesting things that we’ve found is that in summer, although the general distribution pattern is much the same as in autumn, there are actually higher levels of methane in the southern hemisphere. This could be because of the natural circulation occurring in the atmosphere, but has to be confirmed by appropriate computer simulations,” said Fonti.

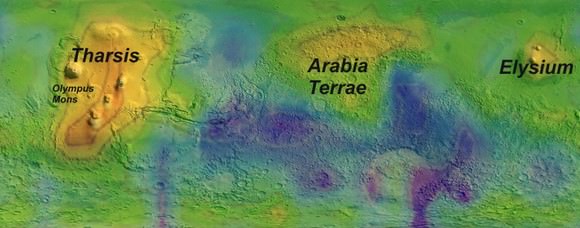

There are three regions in the northern hemisphere where methane concentrations are systematically higher: Tharsis and Elysium, the two main volcano provinces, and Arabia Terrae, which has high levels of underground water ice. Levels are highest over Tharsis, where geological processes, including magmatism, hydrothermal and geothermal activity could be ongoing.

“It’s evident that the highest concentrations are associated with the warmest seasons and locations where there are favorable geological – and hence biological – conditions such as geothermal activity and strong hydration. The higher energy available in summer could trigger the release of gases from geological processes or outbreaks of biological activity,” said Fonti.

The mechanisms for removing methane from the atmosphere are also not clear. Photochemical processes would not break down the gas quickly enough to match observations. However, wind driven processes can add strong oxidisers to the atmosphere, such as the highly reactive salt perchlorate, which could soak up methane much more rapidly.

Martian years are nearly twice as long as Earth years. The team used observations from the Thermal Emission Spectrometer (TES) on Mars Global Surveyor between July 1999 and October 2004. The team studied one of the characteristic spectral features of methane in nearly 3 million TES observations, averaging data together to eliminate noise.

“Our study is the first time that data from an orbiting spectrometer has been used to monitor methane over an extended period, “ Fonti said. “The huge TES dataset has allowed us to follow the methane cycle in the Martian atmosphere with unprecedented accuracy and completeness. Our observations will be very useful in constraining the origins and significance of Martian methane.”

Methane was first detected in the Martian atmosphere by ground based telescopes in 2003 and confirmed a year later by ESA’s Mars Express spacecraft. Last year, observations using ground based telescopes showed the first evidence of a seasonal cycle.